INTRODUCTION

Ehrlichia spp. is an obligate intracellular bacteria with tropism for hematopoietic cells which are transmitted by ticks (1). A number of different species of Ehrlichia can infect dogs including some which usually induce clinical disease and some which cause mild or no symptoms in dogs, but may cause disease in humans (2). Worldwide, Ehrlichia canis is the most important species of Ehrlichia in dogs. E. canis causes Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis (CME) and it is transmitted by the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus (3).

CME is characterized by three clinical forms: acute, subclinical and chronic. The acute one is accompanied by fever, anorexia, lymphadenomegaly, epistaxis and poetechie (4). In the subclinical form, dogs appear healthy despite thrombocytopenia and have the potential to remain persistent carriers (5). This phase may last for years and some dogs will spontaneously eliminate the pathogen, while others will develop chronic form when bone marrow hypoplasia leads to pancytopenia resulting with bad prognosis for the outcome of the infection (6).

Related to its vector R. sanguineus, CME has a wide distribution in the world, particularly in tropical, subtropical and Mediterranean areas and it is considered enzootic in Southern Europe (7). During the last few years, serologic and/or molecular evidence of E. canis has been reported in the neighboring countries of Serbia including Hungary (8), Romania (9) and Bulgaria (10). Epidemiological data, focused on the seroprevalence of CME among companion and hunting dogs in the northern part of Serbia, have been recently published (11, 12). However, there is no epidemiological data regarding the prevalence of E. canis in stray dogs in Serbia. Among stray dogs, this infection is facilitated due to their way of life and lack of anti-parasitic protection. Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the exposure of stray dogs to Ehrlichia canis infection and determine its prevalence using immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) test.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Blood samples of 217 stray dogs (112 females and 105 males) originating from the territory of 7 municipalities, located in 6 different regions in the Republic of Serbia, were sent to the laboratory of the Department of Infectious Diseases of Animals and Bees, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Belgrade, during a 1-year period (from April 2013 to June 2014). All samples were taken from dogs that were processed in the municipality shelters. There was no evidence about their health status and possible tick infestation. Due to the lack of history data on the exact age of the examined dogs, approximate age was determined based on insight into the physical condition and teeth examination, at the same time as blood sampling. Upon arrival at the laboratory, each blood sample was centrifuged, the serum collected, marked and stored at -20°C until analysis. The relevant data for each sample was recorded (place of dog origin, along with gender and approximate age).

For detection and semi-quantitation of IgG class canine antibodies to E. canis, the Ehrlichia canis IFA Canine IgG Antibody Kit (Fuller Laboratories, Fullerton, California, USA) was used according to the instructions of the producer. All untested sera were prepared as 1:50 screening dilutions in PBS. Ten µL of each dilution was applied on 12-well masked slides containing Ehrlichia canis-infected canine DH82 cells. The slides were placed and incubated in a humid chamber for 30 minutes at 37±0.5°C and then washed 3 times with a gentle stream of PBS from a washbottle. To each slide well, 1 drop (10-15 μL) of anti-canine IgG Conjugate was added and all slides have been returned to the humid chamber for another 30 minutes of incubation in the dark place. Finally, the slides were washed again for 3x, air dried and examined under a fluorescent microscope.

Biostatistical analysis was performed by the statistical SPSS package, version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square (x2) test was used for the comparison of prevalence rates among studied age categories and corresponding rates between gender. Differences were considered significant when P< 0.05.

RESULTS

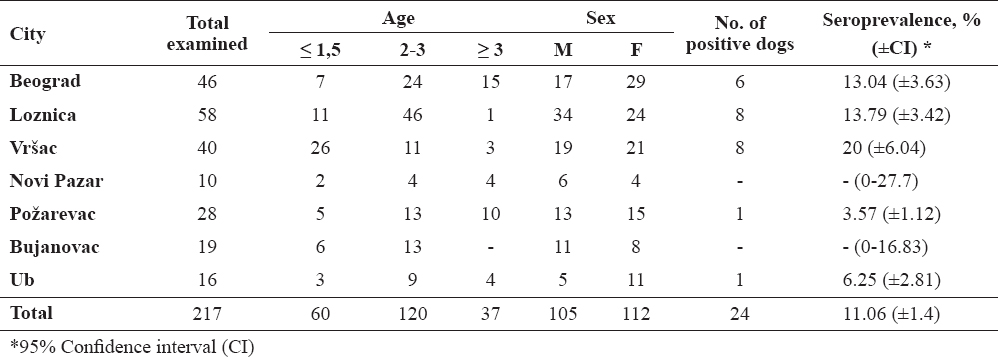

A total of 24 (11.06%) out of 217 examined dogs had a positive IFAT titer of 1:50 or higher to E. canis. Seropositive dogs were found in 5 out of 7 investigated municipalities with a seroprevalence varying from 3.57% to 20% (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of examined and seropositive dogs, according to their origin, age and sex

The highest prevalence was noticed in Vršac (20%), whereas the lowest in Požarevac (3.57%). Spatial distribution of municipalities where sampling was carried out is presented on the map (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The map of Serbia shows cities where the specimens were collected

According to the sex, there was slight difference between female (13/24, 54.2%) and male (11/24, 45.8%) seropositive dogs. According to age, out of all seropositive animals, 10 (41.7%) were younger than 1.5 year (puppies and young adults), 10 (41.7%) were 2-3 years old (adults) and 4 (16.6%) were older than 3 years (elder dogs). Comparison of seroprevalence rates between sexes and age categories, showed no significant differences (P=0.057 and P=0.56, respectively).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the overall seroprevalence of Ehrlichia canis in Serbia was 11.06%, with a range from 0 to 20% depending to the region. The prevalence of E. canis is largely related to some epidemiological factors such as geographical distribution and density of the vector Rhipicephalus sanguineus, animal behavior and the average age of study population (13). Rhipicephalus sanguineusticks are mostly present in tropic and subtropical regions, but there is evidence for their existence in the Mediterranean countries in Europe, for instance in Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Turkey (7), Balkan region (14) and Serbia, as well (15).

Serological or molecular evidence of E. canis infection has been reported worldwide - in regions of the United States (16), in South America − countries Venezuela, Colombia, Chile, Peru, Brazil, Mexico (17); in many countries of Africa and Asia – Tunisia, Egypt, Chad, Zimbabwe, Cameroon, Senegal, Israel, Japan (18) and finally, in the Mediterranean countries of Europe - Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Turkey (19). Meanwhile, in the neighboring countries of Serbia, extensive seroepidemiological investigations that include large number of apparently healthy pet dogs were performed. The highest prevalence was reported in Bulgaria, 37.5% (10), then in Romania, 2.1% (9) and Hungary, 0.16% (8) where only 2 out of 1305 dogs tested positive.

The first report of E. canis in dogs from Serbia was published by Pavlović et al. after detection of morulae in a monocyte on a peripheral blood smear (20). Recently, some serological studies in dogs have been carried out in the northern part of Serbia. Seroprevalence of 16% and 13.79% have been revealed by using IFA test in pet and hunting dogs, respectively (11, 12). Higher prevalence than in our research is probably the result of the sample selection mode. While we have done random selection of dogs, mentioned studies have involved mainly dogs from veterinary ambulances who arrived there because they have had tick(s) attached, or had ticks’ infestation history.

Our study included stray dogs which have spent most of their life on the city streets or in rural environment. Due to their way of life and lack of anti-parasitic protection, stray dogs have more frequent parasite infestations than urban dogs and their life span is short, hardly ever longer than 4-5 years (21). The results of this serosurvey did not reveal any correlation between the age of tested dogs and seropositivity rate, meaning that E. canis affects equally puppies and young adults, adults and elder dogs. This finding is in correlation with the report of Tsachev et al. (10), but opposite to the others (22, 23) in which authors concluded that adult dogs older than 3 years are more susceptible to canine ehrlichiosis. Possible explanations include the immunologic status of the host or more exposure to the vector tick (13).

Although neither the age nor the gender of tested dogs seems to be related to the infection, due to outdoor life which encourages tick’s attachment, we can assume that some of these dogs were probably suffering from acute CME, subsequently recovered, but remained seropositive at the time of testing, while others would be considered as subclinical carriers (24). The inability to distinguish between current infection and prior exposure is widely recognized as a weakness of IFA tests (2).

The seropositivity in some dogs may be the result of cross-reactivity to other Ehrlichia species (25), like E. equi, E. risticii, Neorickettsia helminthoeca and E. ewingii (26) which may pose a serious problem in the interpretation of IFA results. However, all of these microorganisms are still not identified in Serbia, and thus we assumed that did not interfere with our results.

Establishing the final diagnosis of the disease can be challenging due to its different forms, variable/multisimptomatic clinical manifestations and diagnostic method(s) used. Despite all the shortcomings mentioned above, the IFA test is considered as a serological “gold standard” diagnostic technique for E. canis (27); it is the most commonly used technique to monitor canine ehrlichiosis infections and it is more susceptible than any other test. This study’ design predicted implementation of a single test in order to give us trace of infection, after which we planned to do more complex studies that combine serological and molecular methods.

CONCLUSION

Our results clearly indicate that stray dogs are potential carriers of this zoonotic disease and contribute to the spread and maintenance of Ehrlichia canis in Serbia. These are the first data on the presence of E. canis infection in the population of stray dogs in Serbia. Defining of “hot spots” in some regions would be useful for further studies, because there we could potentially find clinical cases.

As the control of canine ehrlichiosis is not possible only through the control of vectors required for transmission of infection, anti-parasitic protection is still the best method of disease prevention. Since the existence and transmission of this infection may be influenced by many factors, future studies should take a multidisciplinary approach, including veterinarians, physicians, ecologists, climatologists and biomathematicians.

The potential role of dogs, as a source of Human Ehrlichiosis, although probably minor, cannot be conclusively excluded. Health professionals should therefore be aware of this possibility and educate patients about Ehrlichia transmission, but without unduly burdening the human–animal bond.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declared that they have no potential conflict of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.