Aedes albopictus (Skuse, 1895) (Diptera: Culicidae), commonly known as the Asian tiger mosquito, is an aggressive daytime biting mosquito currently considered as one of the top 100 invasive species in the world and the most invasive mosquito species (

1,

2). It originates from South-East Asia and in the last 30-40 years it has colonized every continent except Antarctica (

3). This global expansion is a result of the passive transport of its eggs, especially with the trade of used tyres and ornamental plants (1, 4). The eggs are very resistant and can survive for months in unfavourable conditions.

Ae. albopictus possesses high ecological plasticity and undergoes a winter diapause in regions with temperate climate. The larvae in their diapaused eggs do not hatch until the environmental conditions are favourable enough for further development (

4).

The adult female mosquitoes prefer human blood, but can opportunistically feed on a wide range of cold-blooded and warm-blooded animals (

5). This feeding behaviour indicates the role of

Ae. albopictus as a competent vector of at least 26 arboviruses, including dengue, chikungunya and Zika viruses (

3) and several species of

Dirofilaria nematodes (

6). In Europe, the first detection of

Ae. albopictus was in Albania in 1979, and until now it has been recorded in most of the Mediterranean European countries and the eastern Black Sea (

2,

7). In North Macedonia, the first detection of

Ae. albopictus was in 2016 (

8). The authors used ovitraps in 3 locations in the South-Eastern region (near the border with Greece), hatched the collected eggs in laboratory conditions and morphologically identified the mosquitoes as

Ae. albopictus.

In order to evaluate the possible dispersal, in 2017 we performed ovitrap and BG sentinel monitoring on 16 different locations covering the South-Eastern and the Eastern region of North Macedonia, and managed to reconfirm the presence in the South-eastern region and to detect the first

Ae. albopictus in Skopje near the main bus and railway station. This first detection was a citizen report about strange black and white mosquitoes that were causing nuisance during the day. The citizen also sent one dead mosquito to our lab which was identified as

Ae. albopictus. We informed the health authorities and they reacted promptly with immediate, one-time insecticidal treatment of the citizen’s backyard with no following actions. Monitoring for

Ae. albopictus is not routinely conducted, hence the aim of this study was to find out if there were established populations in Skopje, which is the most populated city and the capital of North Macedonia.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The monitoring was carried out in the city of Skopje (42.0000°N, 21.4333°E; 240 m a.s.l. with urban area of 340 km2) in September 2018. We used ovitraps (500 ml black plastic cups) filled with tap water and a masonite strip (12.5 × 2.5 cm) for egg deposition. The plastic cups were modified by punching 2 holes 3 cm from the top of the cup to prevent water overfilling. A total of 50 ovitraps were randomly distributed in all of the 10 Skopje’s municipalities (Aerodorom, Kisela Voda, Gazi Baba, Centar, Butel, Karposh, Gjorche Petrov, Chair, Saraj and Shuto Orizari; 5 ovitraps per municipality). The aerial distance between the traps was min. 300 m. The ovitraps were placed on the ground by qualified personnel, in shaded and accessible places, under vegetation with a free space above of at least 1 m. The ovitraps were left in the same place during the monitoring (14 days). The masonite strips were collected on a weekly basis and delivered to the Laboratory for parasitology and parasitic diseases within the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Skopje. After the masonite collection, the ovitrap was refilled with water and a new masonite strip was placed.

The eggs were hatched at room temperature in entomological cages in the laboratory. The larvae were fed with ground cat food and reared to adults. The adult mosquitoes were euthanized by freezing (-20 °C) and morphologically identified using the MosKeyTool (

9). Additionally, five of the morphologically identified adults were randomly chosen for molecular identification by conventional PCR (

10). Total RNA was extracted from a single mosquito with automatic extraction method using Total RNA/DNA Extraction Kit (Sacace, Italy). Prior to RNA extraction, the mosquitoes were mechanically homogenized and incubated on 56 °C for 90 minutes, in a mixture containing 20 μl Proteinase K + 180 μl Genomic Digestion Buffer (Invitrogen, USA).

RESULTS

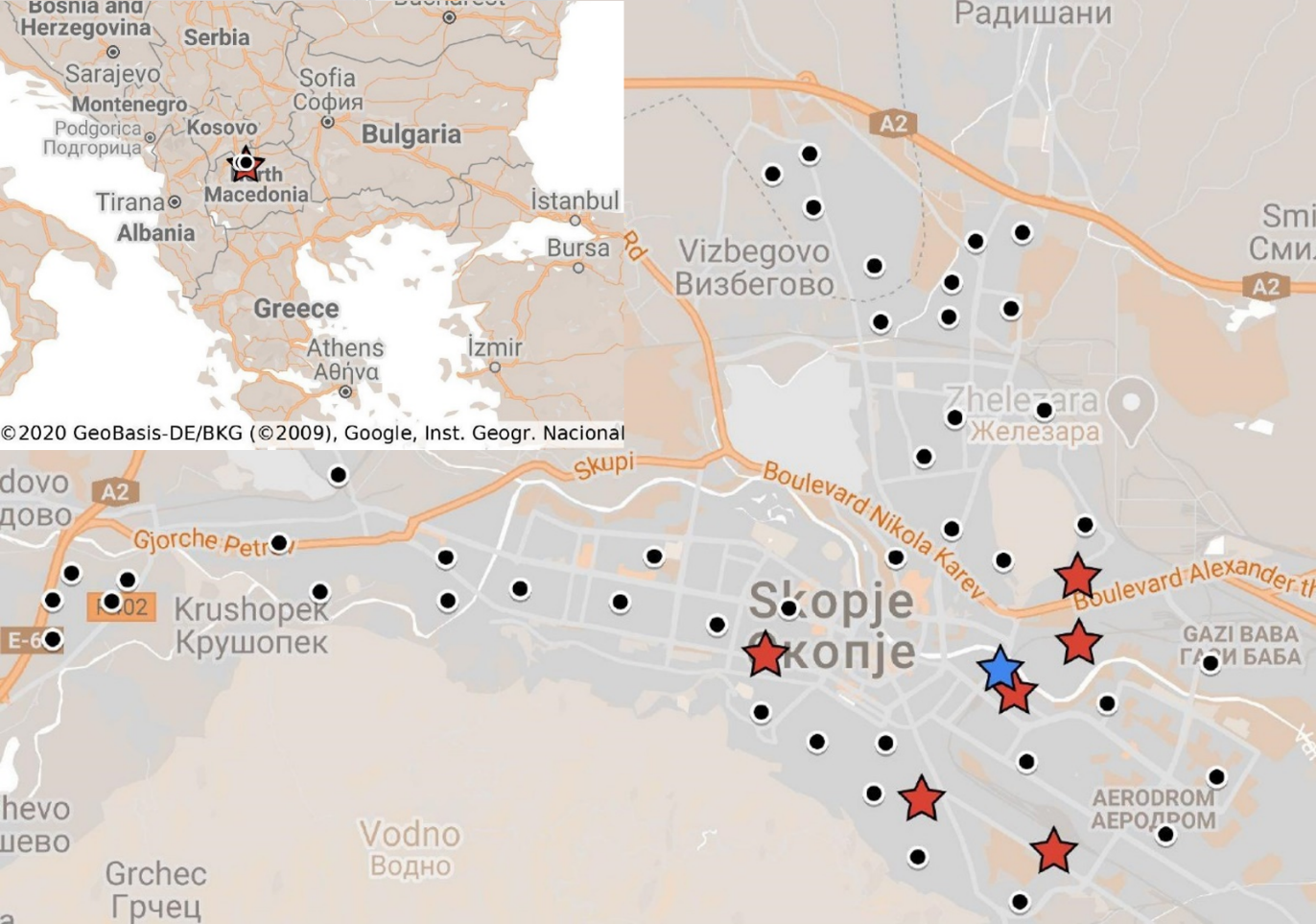

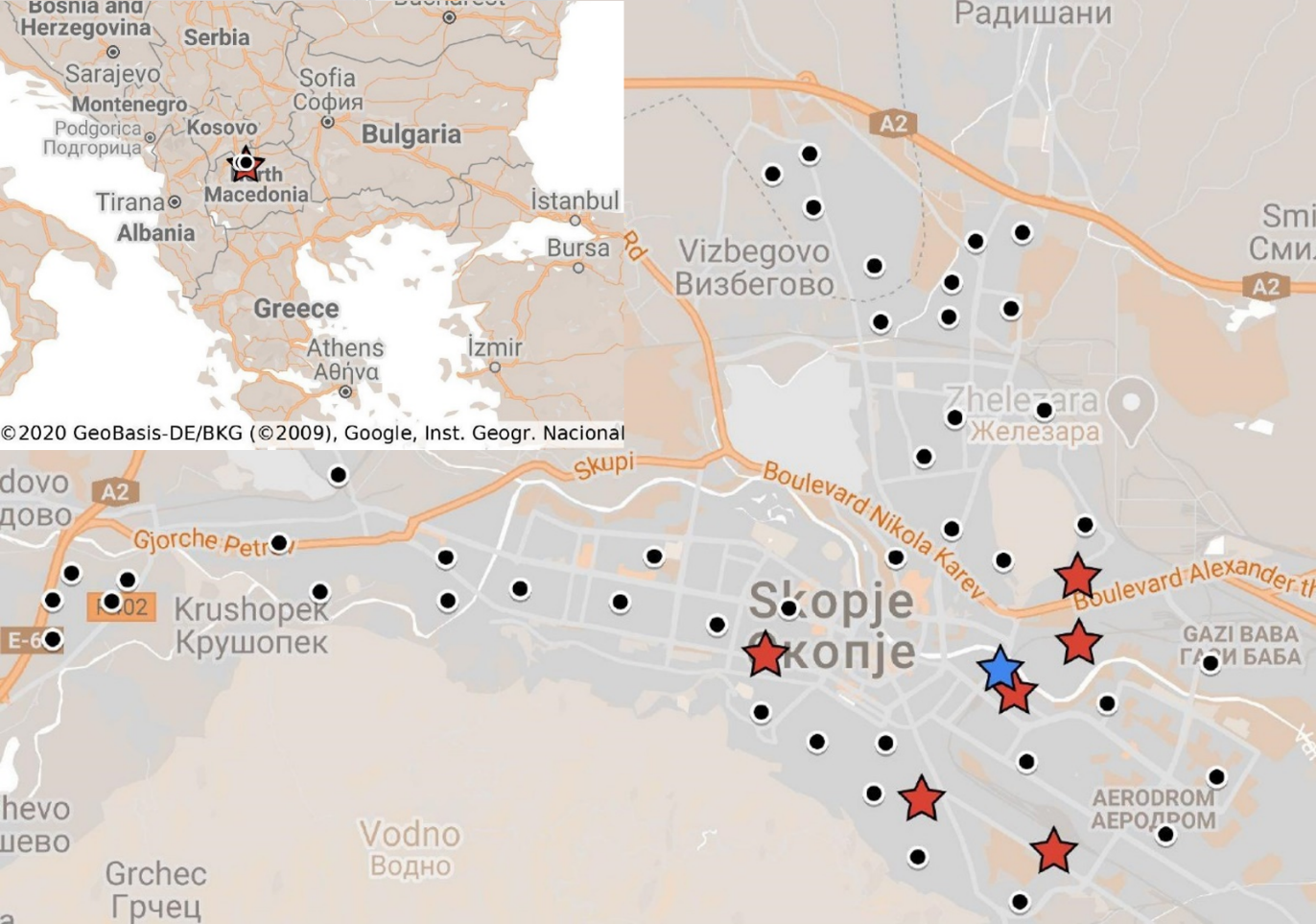

In total, 94

Aedes eggs were collected from 7 (14%) ovitraps in 3 (30%) municipalities (Gazi Baba, Kisela Voda and Centar) (

Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Distribution map of the ovitraps in Skopje

- Positive sites,

- Negative sites,

- Positive site and site of the first detection in Skopje

The egg counts were from 0 to 18 per ovitrap per week. Thirty-eight eggs (40.4%) were successfully hatched and were reared to adults. All of the adult mosquitoes were morphologically identified as

Ae. albopictus. The molecular analysis confirmed the morphological identification (

Fig. 2). No other potentially invasive species were identified during the monitoring period.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Molecular confirmation of

Aedes albopictus by conventional PCR

a -

Aedes albopictus, b -

Culex pipiens, c - molecular marker, d - negative control (m. mix),

e -

Aedes albopictus positive control

DISCUSSION

This study reports an established population of the Asian tiger mosquito by ovitrap monitoring in Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia. The ovitraps were selected as a monitoring method because of their high sensitivity to low mosquito densities, low price and practical use in field conditions (

11). Their downside is that the number of eggs per ovitrap does not correctly estimate the real abundance of the tiger mosquitoes. A single

Ae. albopictus female can oviposit in multiple, different sites, and an ovitrap in the same area can be less attractive than these sites (

12). However, the use of ovitraps for monitoring of invasive mosquitoes is considered as a more sensitive method than the larval surveys, even in low mosquito densities (13). Ovitraps can help in the control of the mosquito population by eliminating the eggs, which results with lower number of mosquitoes. We have expected the introduction and establishment of the

Ae. albopictus due to its presence in the neighbouring countries (Albania, Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia) (

1,

14). Although, they have been present in Albania for more than 40 years, their first detection was made bus and railway station, which further supports our theory that the tiger mosquito was unknowingly dispersed by human activities.

The new data on

Ae. albopictus reported here will raise concern for the health authorities. At present, the role of

Ae. albopictus in the transmission of arboviruses in North Macedonia is unknown, but its presence increases the risk of potential transmissions and should not be neglected. From the medical point of view, the knowledge about present vectors in an area may help influence differential diagnoses of symptomatic patients (

16).

North Macedonia does not have an invasive mosquito monitoring program. Our results strongly suggest an establishment of a national monitoring system to evaluate the spread of the tiger mosquitoes and to monitor other country regions that could potentially be at risk of invasion. The early detection of recent

Ae. albopictus introduction will trigger adequate control strategies in order to limit the potential negative impact of its establishment (

17). The monitored sites should also be checked for other invasive mosquito species, such as

Ae. japonicus which is present in neighbouring Serbia (

14). Our experience with the first report in Skopje suggests that for an early detection of an invasive mosquito species, the involvement of the community (citizen scientists) should be highly encouraged.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study show that the distribution of the Asian tiger mosquito is expanding and poses a risk for an

Aedes-borne disease transmission in North Macedonia. The available data highlight the need for a regular monitoring for tiger mosquitoes to plan adequate control measures.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Giorgia Angeloni from IZSVe and Dr. Stefano Gavaudan from IZSUM in Italy for their invaluable advices for the field work and the mosquito identification methods.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

AC conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. AC, LR, KA, IC and JS performed the field work, larval rearing and the morphological identification. ID, KK and ZP performed the molecular identification. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

10.2478/macvetrev-2020-0025

10.2478/macvetrev-2020-0025