Abstract

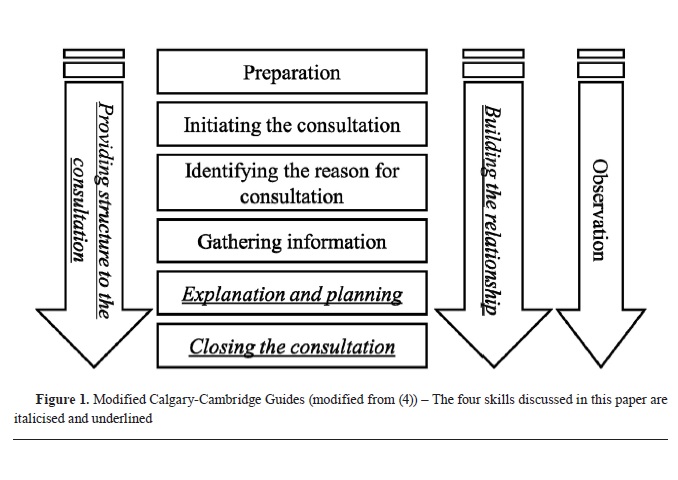

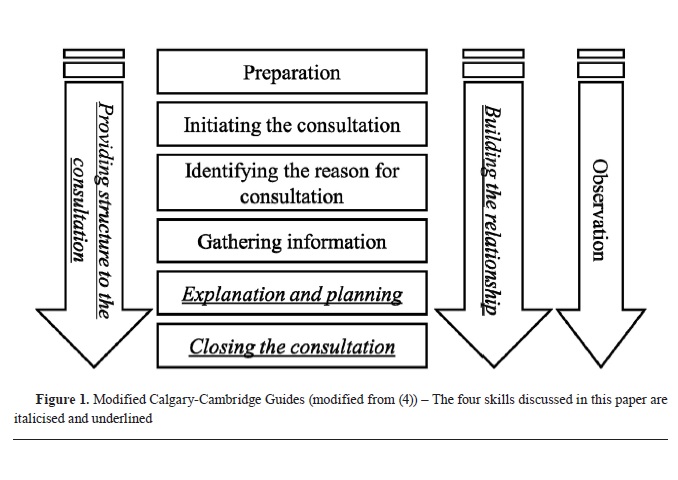

This article, part 2 of a 2-part series, describes the next two steps in the application of the Modified Calgary-Cambridge Guides (MCCG) to consultations in bovine medicine, ‘explanation and planning’, and ‘closing the consultation’, and introduces concepts that are associated with all the components of the guide, ‘building the relationship with the client’ and ‘providing structure to the consultation’. Part 1 introduced the aim and framework of the MCCG which enables the practitioner to gain an insight into the client’s understanding of the problem, including understanding aetiology, epidemiology and pathophysiology. Part 2 introduces the framework that provides the opportunity to understand the client’s expectations regarding the outcome, their motivation and willingness to adhere to recommendations. It also describes how to engage and acknowledge the client as an important part of the decision-making process, how to establish responsibilities of both the client and practitioner, and how to reach out to the client at the conclusion of the consultation to make certain that the client’s expectations were met.

Keywords: bovine practitioner, client-centred, Modified Calgary-Cambridge guide, veterinary communication, veterinary consultation

INTRODUCTION

Establishing a healthy client-practitioner relationship through effective and efficient communication is a key component to the success of a bovine consultation (

1, 2). Creating a friendly environment, taking time to understand and appreciate the client’s perspective, sharing ideas and involving the client in the decision-making process, paves the way to establishing this healthy relationship. Ineffective communication, as determined from the client’s perspective, is one of the leading causes of complaints to the Veterinary Surgeons Board of South Australia. In human medicine, curricula incorporating communication skills improved the patient-practitioner relationship (

3). The Modified Calgary Cambridge Guide (MCCG) provides a structure that can guide the practitioner through the consultation process (

Fig. 1) (

4, 5, 6, 7). The first three components of the guide (‘preparation’, ‘initiating the consultation’ including ‘identifying the reason for the consultation’, and ‘gathering information’) were introduced in part 1 (

2).

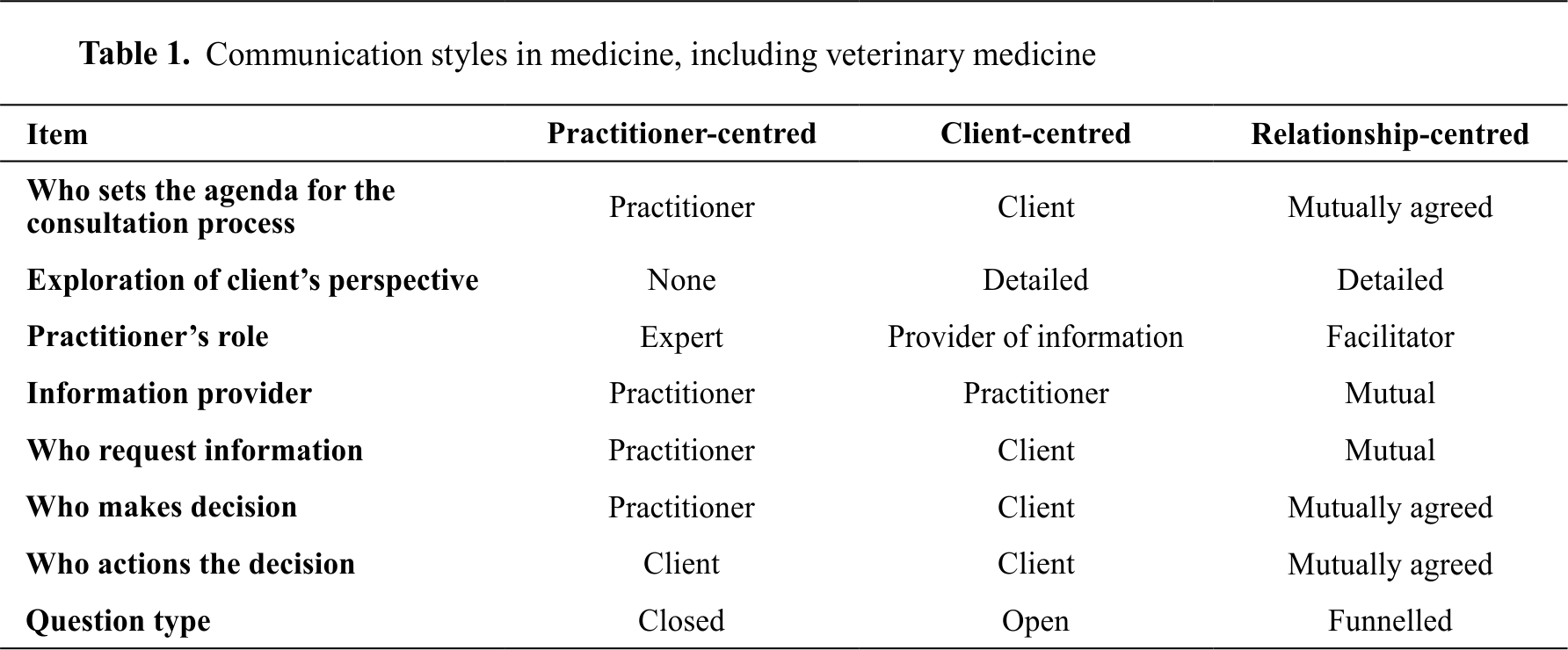

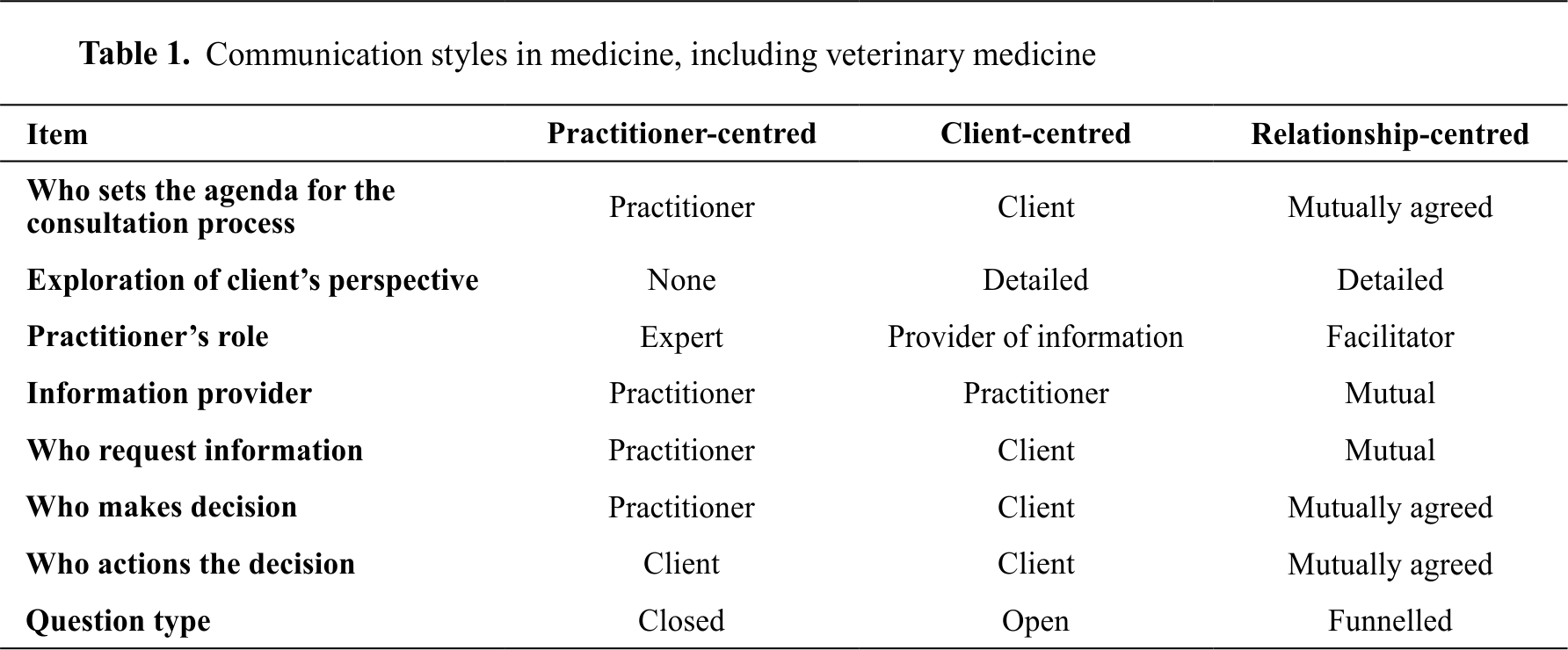

It is important to focus on the use of relationship- centred collaborative communication skills when establishing a client-practitioner relationship, particularly in the bovine production setting (

Table 1). Adherence to treatment recommendations and management plans for the individual patient or the herd is likely to be increased when the approach and decision have been shared and mutually agreed (

9). If the information received through the data collection and evaluation process is incomplete, outcomes will not meet client expectations.

Using the same fertility case of an individual cow (“Margery”) introduced in Part 1, the aim of this paper is to introduce skills that can enhance the ‘explanation and planning’ and ‘closing the consultation’ components of the guide. Running in concert with all of the components of the guide are the skills associated with ‘building the relationship with the client’, ‘providing structure to the consultation’ and ‘observation’. Since practitioners often develop the latter three skills with experience, but the consultation process could be enhanced if utilised more effectively (

4, 5, 8), this paper will also discuss the importance of these components.

PROVIDING STRUCTURE TO THE CONSULTATION

The commonest complaint in human medicine is that doctors do not listen (

19). Clients today demand information, want an explanation about the disease and why it happened, want to know about the medicine (drug) prescribed and want to know how to stop the disease from happening again (preventative measures). To ensure client satisfaction, it is important that the client’s voice is heard. Equally important is the quality of the communication with the client, which will drive the health outcome for the patient (

20).

By providing structure to the consultation, the practitioner can ensure they have a clear understanding of the client’s perspective, can encourage the client to correct any misunderstandings, and can reinforce important details that have been discussed. Providing structure to the consultation involves organisation and logical thinking. Confirming and reinforcing understanding of the client’s perception must link closely with keeping the conversation flowing and on track. The client can interrupt at any time, highlighting the importance of active listening and taking the time to understand, whilst keeping the data collection process on track

Making organisation overt

Skill 18. Summarises at the end of a specific line of inquiry to confirm understanding before moving onto the next section.

The practitioner should use the summary to tie the client’s statements together. This allows the practitioner to show the client that they have been listened to and understood. Summarising also identifies areas that are still to be explored (

10).

‘Let me go over what I understand from what we just talked about. (Provide summary). Am I missing anything?’

Summarising also allows the practitioner to reinforce important matters that have been discussed, stimulate further discussion, collect and/or link ideas, and as a transition indicating a shift in the direction of the discussion (

8, 10, 11).

‘You mentioned that you suspect that Margery had a difficult calving. I think this is important. Can we talk more about it?’

Indeed, the summary can be strategically used to ensure the client has understood what the bovine practitioner has said (

10).

‘Just to make sure you understand what we have talked about so far, would you please summarise what we have discussed?’

Skill 19. Progresses from one section to another using signposting and transitional statements; includes rationale for next section.

The practitioner should ensure adherence to a logical sequence (Skill 20) and the use of transitional statements whilst gaining permission from the client to proceed.

‘If it is ok with you, first I would like to perform a general clinical exam of Margery and then I would like to examine her using an ultrasound scanner to visualise her ovaries.’

Attending to flow

Skill 20. Structures consultation in a logical sequence.

The practitioner should clearly explain to the client how the consultation will be running (

2, 4, 11, 12).

‘My plan is to discuss Margery’s problem with you, then examine her, and then we can discuss what I have found and how to deal with it. Does this sound reasonable?’

Skill 21. Attends to timing and keeping consultation on task

The practitioner should be directive but polite when trying to keep the client on the topic or moving them to a new topic.

‘That does sound interesting. Thank you for telling me. I don’t think it is related to Margery’s problem. I’d like to spend some more time concentrating on investigating her problem. Is that ok with you?’

BUILDING THE RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CLIENT

To build and maintain the relationship with the client, the practitioner should use appropriate non-verbal behaviour (body language) and verbal language, show appreciation of the client’s beliefs, show empathy and sympathy, and accept mutuality (

2, 4, 9, 13).

Communication with the client should use non- technical language to avoid confusing the client. This helps build a relationship with the client.

Non-verbal behaviour

Skill 22. Demonstrates appropriate non–verbal behaviour e.g. eye contact, posture and position, movement, facial expression, use of tone.

Reading the body language of the client is essential in the consultation process. The practitioner may learn more about the client from the way in which they tell the story than from the story itself. To appreciate the body language of a client, the practitioner should be aware of any age, cultural and ethnic differences. The practitioner should be also aware that the client is also doing the same, watching the practitioner’s body language. Consciously or not, throughout the consultation, messages are being sent through both words and behaviour. Posture, gestures, eye contact, and tone of voice are used to subconsciously judge interest, attention, acceptance and understanding.

Some body language can block communication and should be avoided as much as possible. The practitioner must avoid expressing superiority, unfriendliness or lack of trust by crossing arms across the chest. Reactions that portrey disapproval, embarrassment, impatience, boredom or critique should be avoided. These reactions may be unavoidable at times; however, the practitioner should attempt not to express them.

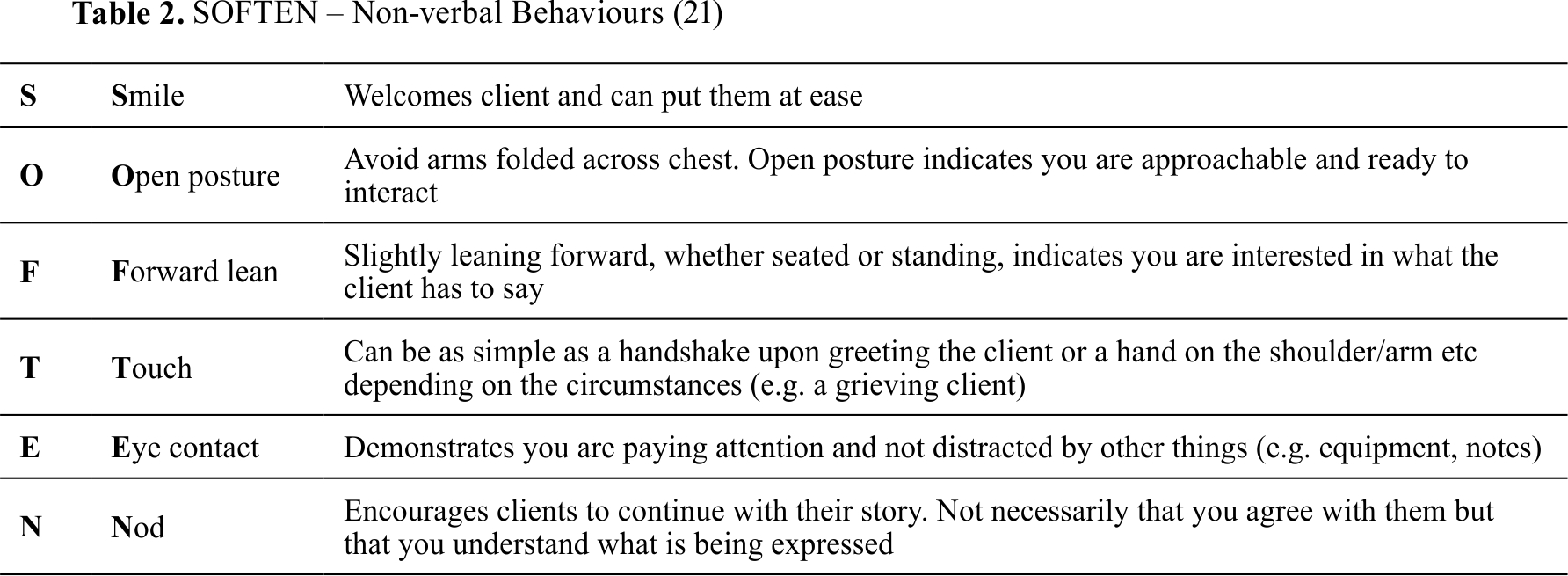

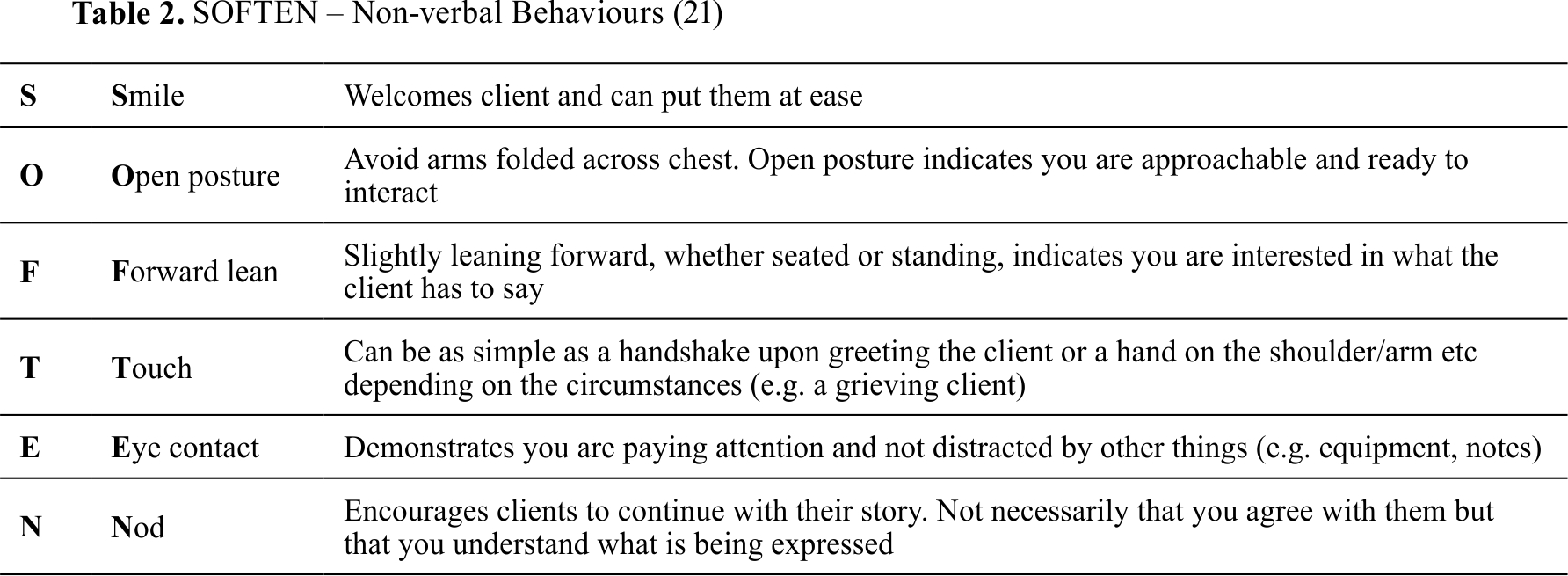

The “SOFTEN” mnemonic is a helpful tool to remember important non-verbal behaviours (

Table 2) (

21). Being aware of the use of non-verbal behaviours and alert to the opportunities in which this form of communication can be utilised to enhance the clinical encounter will foster a positive and productive client-practitioner relationship.

Skill 23. If reading, writing notes or using a computer, do so in a manner that does not interfere with dialogue or rapport.

Note taking by the practitioner should not interfere with the dialogue and the consultation process.

Developing rapport

A positive client-practitioner rapport has the potential to improve the outcome for the patient. It requires collaboration, reciprocity and growth. Signs of a positive client-practitioner rapport include increased and easy flow of conversation, sharing of sensitive information, relaxed body language, increased eye contact, better listening and responding (

21). Effectively and sincerely responding to the client’s emotions will also foster positive rapport and build a strong relationship with the client. Some of the core relationship-building skills are summarised using the “PEARLS” mnemonic (

Table 3) (

21).

Skill 24a. Acknowledges client’s views and feelings; accepts legitimacy; is not judgmental.

The practitioner should accept the legitimacy of client views and is non-judgmental of these views.

‘Sounds like you have read about it. Let’s review what you have read and we can decide together what would be the best approach.’ NOT ‘I don’t think so. It is my opinion that…’

Skill 24b. Demonstrates understanding of the animal’s importance and purpose.

For any production animal, it is essential for the practitioner to demonstrate an understanding of the animal’s purpose, worth and economic justification. This shows the client a recognition of the current economic environment in which they work, and an understanding of the unique relationship that can exist between the patient and its owner.

‘I understand that Margery is an expensive cow and means a lot to you. Let’s discuss what possible tests we should run to confirm the final diagnosis and we will try to keep the cost within your budget. Is this OK with you?’

Skill 25. Uses empathy to communicate understanding and appreciation of the client’s and animal’s feelings or predicament.

Empathy conveys respect to the client. To express empathy, the practitioner should first identify the feelings and perspectives of the client (

13, 14, 15, 16). Empathetic responses include warmth and reflective listening in an effort to understand the feelings and perspectives of the client without judging, criticising or blaming. To identify feelings and perspectives of the client, the practitioner should pay attention to the client’s face, voice, behaviour and words.

It may be better to ask what the client feels rather than assume.

‘How did you feel about……?’.

Once the feelings and perspectives of the client are known, the practitioner should respond empathetically. Empathetic responses can be verbal and non-verbal.

‘I can only imagine how upset not having Margery in-calf is for you, but I am delighted to see you are continuing trying to get her in calf.’

This statement gives credit to the client, encourages them and promotes self-esteem. This is a motivational approach to a general consultation.

Non-verbal empathetic responses can be expressed by an empathetic nod, handing a box of tissues to a client who is near to tears, and gently placing a hand on the client’s shoulder or arm in support.

Empathy should be differentiated from sympathy, which is an emotional state.

Skill 26. Provides support to the client: expresses concern, understanding, willingness to help; acknowledges coping efforts and appropriate animal care; offers partnership.

Support is a response that indicates an interest in or an understanding of the client (

5, 7, 11, 17). An important time to use support is immediately after a client has expressed strong feelings. Support can be expressed by using techniques such as reassurance and empathy. Supportive remarks such as

‘I understand’ promote a feeling of security in the relationship between the practitioner and the client (

18).

‘I can understand how this situation with Margery is upsetting.’

Skill 27. Deals sensitively with embarrassing and disturbing topics and physical pain, including when associated with physical examination of the animal.

The practitioner should be able to recognise potentially offensive or embarrassing questions. To put the client at ease, it may be necessary to elaborate the need of asking these questions.

‘I apologise if the next few questions may be uncomfortable for you but I need to know something about your regular management of…’

It is also important to recognise that some procedures may be more invasive and, particularly for less experienced clients, may feel not essential. Therefore, the practitioner should ensure the client is aware of the importance of the procedure, acknowledging the invasiveness.

‘I am aware that this may feel uncomfortable for Margery. However, it is essential to carry out the rectal examination to assess the situation with the reproductive organs inside.’

Involving the client

The client should be involved in the consultation process. To stimulate this, the practitioner should think aloud and explain why some steps are being carried out or inquired about.

Skill 28. Shares thoughts with clients to encourage their involvement.

To stimulate client participation in the consultation process, the practitioner should think aloud and explain why a particular step is being carried out.

‘What I’m thinking about now is how to restrain Margery for the ultrasound examination that we talked about.’

Skill 29. Explains rationale for questions or parts of physical examination that could appear to be irrelevant.

‘I am doing a full clinical examination of Margery as there is a small possibility that she is not cycling because something else is going on.’\

Involving the animal (s)

Skill 30a. Acknowledges the animal and / or alerts the animal to the practitioner’s presence.

This skill should reassure the client that the practitioner is aware of the value of this particular animal to them.

‘I admire the structure and shape of Margery’s udder. Is she one of your show cows?’

Skill 30b. Relates to the animal, taking into account the relationship between the client and the animal. Approaches and handles the animal sympathetically.

‘It seems that we will have to examine Margery using rectal examination and an ultrasound scanner. Do you mind if we put her in the crush for a while?’

EXPLANATION AND PLANNING

The relationship developed with the client becomes extremely important in the explanation and planning component of the consultation process (

2, 6, 8, 11). Explaining the meaning of the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis is a complex process and it is essential to determine the client’s understanding of this information. In plain, non- technical language, the client should be informed on why ‘Margery’ is not cycling and ensure they have understood the practitioner’s explanation. It is important to clarify the client’s own perspective as to why Margery is not cycling, observe their reaction to your explanation and address any concerns they have.

Within the planning or decision-making aspect, the role of the practitioner should be to explain all possible options, further tests required, and ask the client for their opinion of which of these are applicable for their situation. In the end, a mutual plan of action including what, when, how and by whom should be made.

‘I’ve gone over why Margery is not cycling and several options to treat Margery’s problem. How you feel about it?’

‘Now that we have several options, let’s decide together what would be the best approach for you. Is that ok?’

Providing the correct amount and type of information

The practitioner should aim to give comprehensive and appropriate information which addresses each individual client’s information needs. The practitioner should not overload the client with information, nor should they restrict information. Providing information in chunks, giving the client time to process information and addressing their concerns with more information as required will ensure that a collaborative approach to the problem is achieved, enhancing the health of the client-practitioner relationship.

Skill 31. Assesses client’s starting point: asks for client’s prior knowledge early on when giving information, discovers extent of client’s wish for information.

‘I admire how much reading you have done on non-cycler cows. Can you tell me what you know about this problem so that we can build onto it? Is there anything else you would like to know?’

Skill 32. Chunks and checks: gives, in easily assimilated chunks, essential information regarding diagnosis and treatment options, prognosis and financial implications; uses client’s response as a guide to how to proceed.

‘It is most likely that Margery is a so-called silent heat cow, or she is in heat for a very short time. She should return in heat in less than two weeks. Based on the findings from the clinical examination and scanning, the good news is that Margery is cycling normally. Do you have any questions you would like me to answer?’

‘There are several options we have to detect her in heat. Should we discuss each one so we can decide together what would be the best and most cost-effective approach for you?’

Skill 33. Gives other information according to the client’s wishes. e.g. aetiology.

‘Would you like to review why I think the problem has occurred and discuss some prevention options in order to avoid future cases?’

Skill 34a. Gives explanation at appropriate times: avoids giving advice, information or reassurance prematurely.

‘The ultrasound scan shows normal sized ovarian follicles, these are the bubbles on the ovary that release the egg. Next, we need to confirm that the eggs are actually being released.’

Skill 34b. Prioritises information given: recognises that some information may be best provided at a later time.

‘Let’s concentrate on the results of the ultrasound scan first, but I’d like to go back to her decreased appetite at the end.’

Aiding accurate recall and understanding

It is important to make the information easy for the client to remember and understand. The use of non-technical language was discussed in part 1 (

2).

Skill 35. Organises explanation: divides into discrete sections, develops a logical sequence.

‘Let’s review what we have discussed. You will monitor Margery in the next two weeks and you will carry out milk progesterone tests on the agreed days. If Margery is not seen in heat this time, we will put a progesterone device in her vagina and stimulate her hormonally. You will then inseminate her at a fixed time afterwards. Do you have any questions about this?’

Skill 36. Uses explicit categorisation or signposting.

‘There are three important things that I would like to discuss. First...’

‘Now, shall we move on to ….’

Skill 37. Uses repetition and summarising to reinforce information.

‘So, to summarise, you will increase observations of Margery and if she is not detected in heat, we will use a vaginal device and hormones to control when she will show heat.’

Skill 38. Uses concise, easily understood language, and either avoids or explains jargon.

‘The vaginal device will help develop a follicle, that bubble on the ovary, and the hormone we give will help release the egg. This ensures she is ready to be inseminated.’

Skill 39. Uses visual methods of conveying information: diagrams, models, written information and instructions.

‘I realise that taking control of Margery’s heat cycle may seem complicated. However, I have prepared a diagram for you that explains everything we will do.’

Skill 40. Checks client’s understanding of information given (or plans made).

‘Does the diagram look OK to you; do you need more information about what we will be doing?

Achieving a shared understanding: incorporating the client’s perspective

The practitioner should provide explanations and plans that relate to the client’s perspective, discover the client’s thoughts and feelings about the information given, and encourage an interaction rather than one-way transmission.

Skill 41. Relates explanations to client’s initial concerns, e.g. previously elicited ideas, concerns and expectations.

‘I hope this answers your previously expressed concern about Margery being a non-cycler or, would you like additional information?’

Skill 42. Provides opportunities and encourages the client to contribute, to ask questions, seek clarification or express doubts. Responds appropriately.

‘We have discussed a lot of information today. To make sure we are both of the same understanding, can you please tell me what treatment we have decided for Margery?’

‘I’m glad we clarified that before I left. I must not have been as clear as I tried to be. I thought we agreed that you would…’

Skill 43. Recognisesverbalandnon-verbalcues e.g. the client’s need to contribute information or ask questions, information overload or distress.

Non-verbal cues include long periods of silence, sudden withdrawal from the conversation, lack of eye contact, brief answers and defensive body language.

‘It looks like you are feeling overwhelmed with all the information we have discussed. I know that it is not what you were expecting to hear. Do you have some questions you would like me to answer?’

Skill 44. Elicits client’s beliefs, reactions and feelings regarding information given, terms used, financial implications; acknowledges (empathises) and addresses where necessary.

‘What concerns you the most about these treatment options? Are they easy to implement on your farm?’

‘I can see that the cost of the treatment is troubling you. Would you like to discuss the benefit of each treatment option again?’

Planning: appropriate shared decision-making

Clients need to understand and be involved in the decision-making process. Mutually deciding on the level of intervention they wish to make will increase the clients’ commitment to the plans that are made.

Skill 45. Shares own thoughts: ideas, thought processes and dilemmas.

‘I understand what you are saying. I worry about the money side of things to. I can put some figures together to indicate where your benefits are going to be so you can see the dollar value.’

Skill 46. Offers choices rather than giving directives.

‘There are several options we have to detect her in heat. We can increase the number of observations, or use heat detection aids, or we could synchronise her with hormones. Would you like to discuss each of these further so we can decide together what would be the best approach for you?’

Skill 47. Encourages client to contribute their thoughts, ideas, suggestions and preferences.

‘Today we have discussed why Margery is not getting in calf and how we can help correct this. Do you agree with what we have discussed? Tell me what you think about it?’

Skill 48. Negotiates a mutually acceptable plan.

‘Based on our discussion, Margery is due to return in heat in 2 weeks. An option is to increase observations for the next 2 weeks to detect her next heat and, if she is missed, use hormonal treatment and fixed time artificial insemination to get her in calf. Do you agree?’

Skill 49. Encourages client to make decisions to the level that they wish, i.e. informed consent.

‘Another option is to go straight to intervening with hormonal treatments to get her in calf. Which would you prefer?’

Skill 50. Checks with client if they accept plans, if concerns have been addressed.

‘So, to clarify the plan, you will increase observations of Margery and if she is not detected in heat, we will use a vaginal device and hormones to control when she will show heat. Do you agree? Have I addressed your concerns?’

CLOSING THE CONSULTATION

To close the consultation, it is important to allow the client to express their opinion about the conclusions arrived at and to discuss the expected final outcome. Further items should be addressed and any corrections made, including what to do if the agreed plan does not work, and a summary given. It is important to thank the client before saying the usual goodbye.

Summarising

Skill 51. Summarises session briefly and clarifies plan of care.

‘So, let’s see what we found. (give summary). The agreed plan is to (give summary). Do you have any questions regarding this?’

Forward planning

Skill 52. Safety nets, explaining possible unexpected outcomes, what to do if plan is not working, and when and how to seek help.

‘If Margery is not detected in heat this time, we will put a progesterone device in and stimulate her hormonally, before you inseminate her at a fixed time afterwards. Please call the clinic in three weeks to let us know whether you caught Margery in heat and have inseminated her. You can leave a message with the receptionist.’

Skill 53. Contracts with client regarding the next steps for client, patient(s) and practitioner.

‘OK. Let’s see what we have to do. You will be monitoring Margery for heat in the next three weeks. I will send you the results of the test and a brief explanation of what they mean. Please feel free to call us if you need more explanations.’

Skill 54. Final check that client agrees and is comfortable with plan and asks if any corrections, questions or other items to discuss.

‘It’s time for me to go. Do you have any further questions about what we have discussed today?’

This provides an opportunity for the client to make the final enquiries about discussed topics but clearly states that is not the time to bring up new topics. However, clients often bring up new topics after questions of this type. The practitioner should strategically reassure the client of the ongoing interest and make plans to address the newly introduced topic at a future time. Reaffirming to the client that interest for ongoing improvement is always appreciated by them.

‘It sounds like this problem may be important and needs investigating. Probably, the best option is to make an appointment in the next few weeks so we can allocate some time to discuss it in more detail.’

This approach should change if the newly introduced topic is of a vital importance for the client.

Skill 54a. Says goodbye.

It is important to reinforce the overall message and encourage the client to implement the agreed plan. Acknowledging the client by making appropriate eye contact and smiling whilst shaking hands leaves the client-practitioner relationship on a positive note.

‘OK Jack, good luck with Margery and let me know how you get on. Enjoy the rest of your day.’

CONCLUSION

The veterinary profession is a service industry and in order to be effective at servicing clients, the practitioner must understand what the client needs and how best they can meet those needs. The practitioner often struggles with the dual role of scientific advisor and effective communicator. A famous quote by Mahatma Gandhi highlights the importance of communication skills to ensure a successful bovine practice; “A customer is the most important visitor on our premises. He is not dependent on us, we are dependent on him. He is not an interruption to our work, he is the purpose of it. He is not an outsider in our business, he is part of it. We are not doing him a favour by serving him, he is doing us a favour by giving us an opportunity to do so”. Communication, both verbal and non- verbal, is the cornerstone for building a healthy relationship with the client. Consultation style and the success of the consultation will directly influence the outcome of the consultation and adherence to treatment recommendations. The modified Calgary-Cambridge Guides may assist in achieving a successful consultation and can be used for teaching future practitioners.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Associate Professor Michelle McArthur for her contribution to Part 1 of this series and her tireless efforts to facilitate communication techniques into bovine consultations within the teaching curriculum and the workplace.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

ANC, RNK and KRP equally contributed to the writing of this review.

APPENDIX – LIST OF SKILLS (22, 23)

Preparation

Establishing context

Skill 0a. Familiarises with past history relating to client and animal(s)

Skill 0b. Anticipates potential conflict or difficulties relating to the client, the animal and to systems and infrastructure

Creating a professional, safe and effective environment

Skill 0c. Ensures facilities/environment are professional and appropriate to anticipated needs

Observation

Skill 0d. Continuous observation of the animal, the client and the environment

Initiating the session

Establishing initial rapport

Skill 1. Greets the client; obtains/confirms client’s name and the name/identity of the animal

Skill 2. Introduces self, role and nature of the consultation; obtains consent

Skill 3. Demonstrates interest, concern and respect for the client and the animal

Skill 3a. Attends to client’s and animal’s physical comfort

Identifying the reason for the consultation

Skill 4. Identifies the client’s problem or the issues that the client wishes to address

Skill 5. Listens attentively to the client’s opening statement, without interrupting or directing the client’s response

Skill 6. Check and screens for further problems Skill 7. Negotiated agenda taking both the client’s and practitioner’s needs into account

Gathering information

Gathering history

Exploration of client’s problem

Skill 8. Encourages client to tell the story of the animal’s problem/s from when it first started to the present in their own words

Skill 9. Uses open and closed questions, appropriately moving from open to closed

Skill 10. Listens attentively, allowing the client to complete statements without interruptions and leaving time for the client to think before answering

Skill 11. Facilitates the client responses verbally and non-verbally

Skill 12. Picks up verbal and non-verbal cues from the client, checks out and acknowledges as appropriate

Skill 13. Clarifies statements that are vague or need amplification

Skill 14. Periodically summarises to verify own understanding of what the client has said

Skill 15. Uses concise, easily understood language, avoiding or adequately explaining jargon

Additional skills for understanding client perspective

Skill 16a. Determines and acknowledges client’s ideas and concerns regarding each problem

Skill 16b. Determines and acknowledges client’s expectations

Skill 16c. Determines and acknowledges how each problem affects the client

Skill 17. Encourages expression of the client’s feeling and thoughts

Providing structure

Making organisation overt

Skill 18. Summarises at the end of a specific line of inquiry to confirm understanding before moving onto the next section

Skill 19. Progresses from one section to another using signposting; includes rationale for next section

Attending to flow

Skill 20. Structures consultation in a logical sequence

Skill 21. Attends to timing and keeping consultation on task

Building the relationship with the client

Non-verbal behaviour

Skill 22. Demonstrates appropriate non–verbal behaviour e.g. eye contact, posture and position, movement, facial expression, use of tone

Skill 23. If reads, writes notes or uses computer, does so in a manner that does not interfere with dialogue or rapport

Developing rapport

Skill 24a. Acknowledges clients’ views and feelings; accepts legitimacy; is not judgmental

Skill 24b. Demonstrates understanding of the animal’s importance and purpose

Skill 25. Uses empathy to communicate understanding and appreciation of the client’s and animal’s feelings or predicament

Skill 26. Provides support to the client: expresses concern, understanding, willingness to help; acknowledges coping efforts and appropriate animal care; offers partnership

Skill 27. Deals sensitively with embarrassing and disturbing topics and physical pain, including when associated with physical examination of the animal

Involving the client

Skill 28. Shares thinking with client to encourage client’s involvement

Skill 29. Explains rationale for questions or parts of physical examination that could appear to be irrelevant

Involving the animal (s)

Skill 30a. Acknowledges the animal and/or alerts animal to their presence

Skill 30b. Relates to theanimal, takingintoaccount the relationship between the client and the animal. Approaches and handles the animal sympathetically

Explanation and planning

Providing the correct amount and type of information

Skill 31. Assesses client’s starting point: asks for client’s prior knowledge early on when giving information, discovers extent of client’s wish for information

Skill 32. Chunks and checks: gives, in easily assimilated chunks, essential information regarding diagnosis and treatment options, prognosis and financial implications; uses client’s response as a guide to how to proceed

Skill 33. Gives other information according to the client’s wishes. e.g. aetiology

Skill 34a. Gives explanation at appropriate times: avoids giving advice, information or reassurance prematurely

Skill 34b. Prioritises information given: recognises that some information may be best provided at a later time

Aiding accurate recall and understanding

Skill 35. Organises explanation: divides into discrete sections, develops a logical sequence

Skill 36. Uses explicit categorisation or signposting

Skill 37. Uses repetition and summarising to reinforce information

Skill 38. Uses concise, easily understood language, and either avoids or explains jargon

Skill 39. Uses visual methods of conveying information: diagrams, models, written information and instructions

Skill 40. Checks client’s understanding of information given (or plans made)

Achieving a shared understanding: incorporating the client’s perspective

Skill 41. Relates explanations to client’s initial concerns. e.g. previously elicited ideas, concerns and expectations

Skill 42. Providesopportunities andencouragesthe client to contribute, to ask questions, seek clarification or express doubts. Responds appropriately

Skill 43. Recognises verbal and non-verbal cues e.g. the client’s need to contribute information or ask questions, information overload or distress

Skill 44. Elicits client’s beliefs, reactions and feelings regarding information given, terms used, financial implications; acknowledges (empathises) and addresses where necessary

Planning: appropriate shared decision making Skill 45. Shares own thoughts: ideas, thought processes and dilemmas

Skill 46. Offers choices rather than giving directives

Skill 47. Encourages client to contribute their thoughts, ideas, suggestions and preferences

Skill 48. Negotiates a mutually acceptable plan Skill 49. Encourages client to make decisions to the level that they wish, i.e. informed consent

Skill 50. Checks with client if they accept plans, if concerns have been addressed

Closing the consultation

Skill 51. Summarises session briefly and clarifies plan of care

Forward planning

Skill 52. Safety nets, explaining possible unexpected outcomes, what to do if plan is not working, and when and how to seek help

Skill 53. Contracts with client regarding the next steps for client, patient(s) and practitioner

Skill 54a. Final check that client agrees and is comfortable with plan and asks if any corrections, questions or other items to discuss

Skill 54b. Says goodbye

10.2478/macvetrev-2023-0011

10.2478/macvetrev-2023-0011