Mac Vet Rev 2025; 48 (1): 77 - 85

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0017

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0017

Received: 16 June 2024

Received in revised form: 23 October 2024

Accepted: 27 November 2024

Available Online First: 25 February 2025

Published on: 15 March 2025

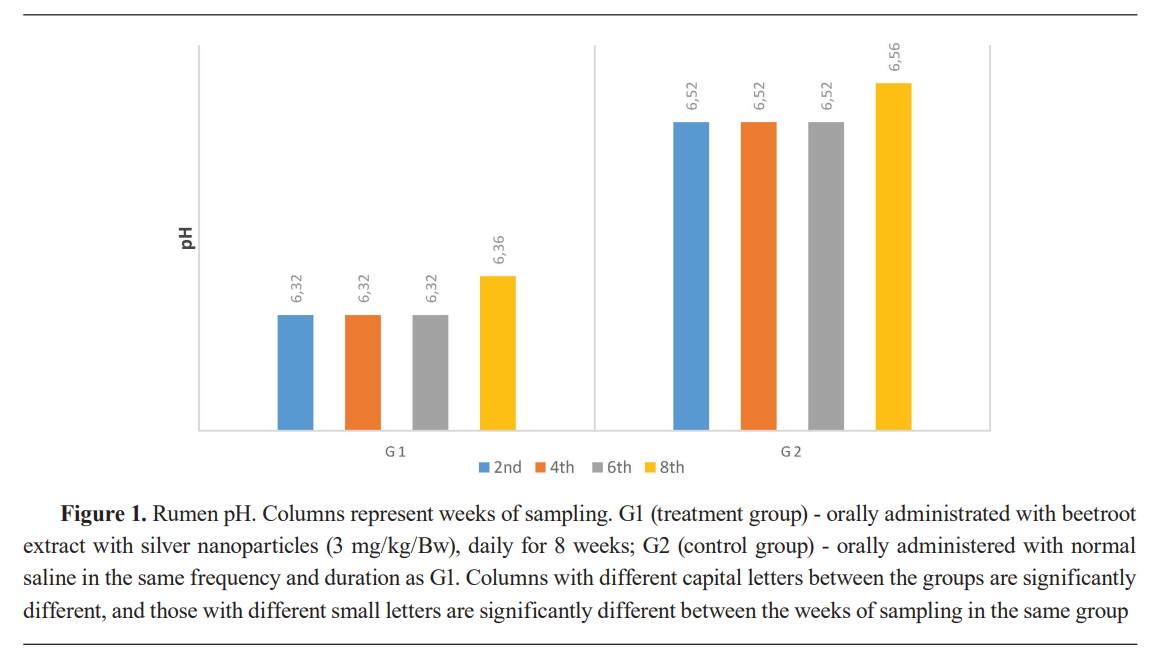

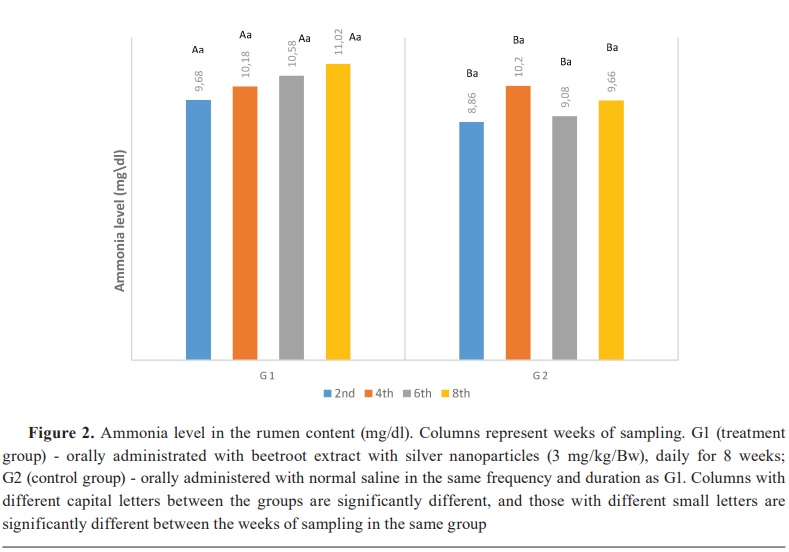

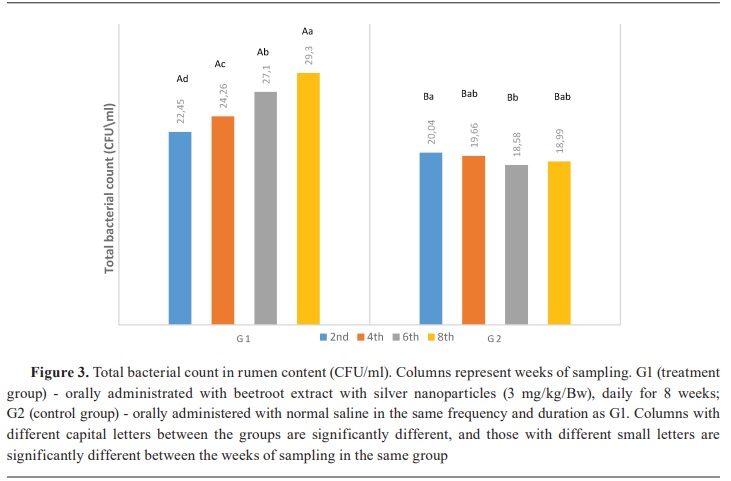

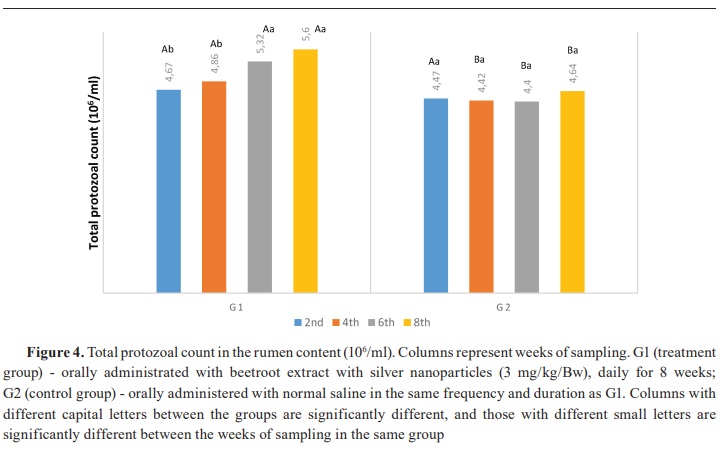

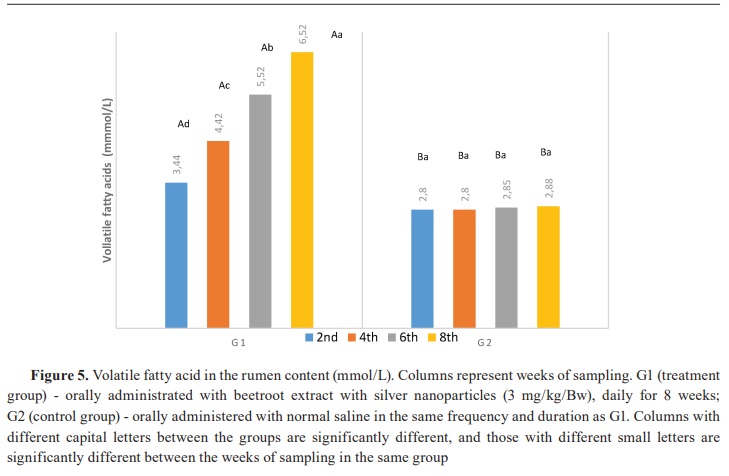

Keywords: beetroot, silver nanoparticles, lambs, rumen, ammonia, volatile fatty acid

© 2025 Dawood T.N. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The authors declared that they have no potential lict of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Macedonian Veterinary Review. Volume 48, Issue 1, Pages 77-85, e-ISSN 1857-7415, p-ISSN 1409-7621, DOI: 10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0017