Septicemia is a significant threat to newborn calves, often due to inadequate colostrum intake in the first day of life. The study aimed to assess the effects of a newly developed herbal formulation on septicemia induced by Escherichia coli strain O111:H8. Ten Holstein-Friesian calves aged 8-10 days were divided into two groups. Experimental septicemia was induced for all calves (n=10). The treatment group (n=5) received a herbal formulation containing extracts from Rosa canina, Urtica dioica, Tanacetum vulgare, selenium, flavonoids, and carotenes, in addition to antibiotics. The control group (n=5) received a placebo (5% dextrose) along with antibiotics for five days. The animals were monitored for 14 days. Blood samples were analyzed for cytokines, cardiac enzymes, renal function, and total antioxidant capacity before and after treatment. The treatment group had non-significantly higher CD4+ counts compared to the control. The serum level of IL-6 increased after treatment, with a considerable difference between the groups at 72 h (p=0.0014). The herbal formulation positively impacted renal and cardiac function evidenced by decreased cardiac troponin I levels and increased total antioxidant capacity (TAC). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels changed significantly over time (p<0.05), with a positive correlation between ECG changes and peak LDH levels (p<0.05). The increased cytokines beside ameliorative effects on heart and kidney functions suggest that the herbal drug may possess immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties that aid in managing the inflammatory response during sepsis. These findings support the use of this herbal-based drug as an adjunctive treatment in veterinary practices for managing septicemia in calves.

Septicemia is a highly fatal disease that primarily affects calves under 2 weeks of age. It remains the leading cause of worldwide economic and productivity loss for cattle herds. The disease is often caused by severe prior illness or a failure to transfer passive immunity, leading to high morbidity and mortality rates in the cattle industry (

1, 2, 3). Birth season and environmental risk factors are associated with the expected occurrence and levels of neonatal death, which have also been predicted to be a risk factor for diarrhea outbreaks (

4).

Sepsis is caused by various pathogens, with

Escherichia coli (

E. coli) being the most commonly isolated organism from blood cultures in septicemic calves, lambs, and foals. This bacterium is prevalent and found in soil, surface water, and feces of animals and humans.

E. coli can cause septicemia and diarrhea in various hosts, including avian (

5), animals, and humans (

6). Calves are particularly vulnerable at two age intervals: 1 to 3 days and 3 to 8 weeks old (

7, 8, 9).

Enteropathogenic

E.coli O111 (EPEC) is one of the most widespread (

10) and deadly diseases, even in developing countries (

11, 12, 13). These pathogenic strains of

E. coli cause severe diarrhea, dehydration, fever, weakness, and depression, causing economic losses in dairy and beef calf production (

14, 15).

E. coli has become a significant cause of diarrhea in newborn calves, often leading to substantial economic losses. This includes increased morbidity and mortality rates, reduced growth rates, higher treatment expenses, and wasted time managing the affected animals. The occurrence of sepsis due to different pathogens in calves demands a critical response and concentration on rehabilitation. The primary treatment includes prescribing antimicrobial agents, fluid therapy, and anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory drugs (

7, 16, 17).

Treatment for sepsis necessitates timely, systematic antimicrobial, fluid, and anti inflammatory intervention. The optimal approach to treating septic cases revolves around managing the infection, decreasing inflammatory reactions, and delivering essential care (

14). Administering immune modulators to enhance immune function in domestic animals during key developmental stages, such as the neonatal period, weaning, and before vaccination and transportation, can decrease economic losses caused by infectious diseases (

18).

Infections cause inflammation, which activates the immune system. Cytokines are key in starting and enhancing innate and adaptive immune responses. However, excessive cytokine production can weaken innate immunity, increasing co-infection risk. Therefore, controlling inflammation and immune responses may help manage sepsis (

19, 20). Nowadays, the role of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of sepsis and subsequent side effects is noticeable (

19, 21). The cytokines released due to sepsis have neurotoxic effects and cause nerve damage. They also have cardiovascular effects which is exhibited by in between interaction, contributing to the pathological process of ischemic stroke (

20, 22).

Conventional methods for preventing or treating bacterial septicemia depend on antimicrobial drugs, which can harm public health and the environment due to drug-resistant microorganisms and antibiotic residues. There is increasing interest in discovering new, plant-based products as safe, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly alternatives for disease management (

23). In traditional china medicine, the herbal drug which is derived from the

Xuefu Zhuyu decoction, has been an approved injectable treatment in China since 2004 for conditions such as sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). This herbal injection is formulated from a blend of several medicinal plants, including the flower of

Carthamus tinctorius, the root of

Paeonia lactiflora, the root of

Salvia miltiorrhiza, the rhizome of

Ligusticum chuanxiong, and the root of

Angelica sinensis. Numerous meta analyses indicate that incorporating mentioned drug into standard sepsis management may significantly decrease the 28-day mortality rate among patients, lower the occurrence of complications, and enhance overall patient outcomes (

24).

Several herbs known for their anti-inflammatory effects have been found to inhibit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation in animal models by reducing IL-6 and IFN-γ production, mainly through the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Key plants studied include

Andrographis paniculata, Zingiber officinale, Curcuma longa, Piper nigrum, Syzygium aromaticum, Momordica charantia, and

Centella asiatica.

Z. officinale, in particular, has been extensively researched and shows significant potential for therapeutic use in sepsis. While both extracts and active compounds from these herbs demonstrate potential antiseptic properties, their effectiveness is primarily attributed to specific active constituents within each plant (

25).

Colisepticemia is an immune-mediated disease that significantly impacts the economic conditions of industrial dairy farms. It is characterized by the invasion of coliform bacteria into the bloodstream and is typically observed in neonates and immune compromised animals. Affected animals exhibit pronounced signs of systemic disease and tend to deteriorate rapidly. Prescribing and consuming natural-based immunomodulatory medications may be effective in improving health conditions, reducing antibiotic intake, and modulating host defense. Scientists have recently encountered re emerging diseases with complicated symptoms that lack specific drugs to relieve side effects and symptoms. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of herbal medicines containing

Rosa canina,

Urtica dioica (nettle),

Tanacetum vulgare (tansy), selenium, flavonoids, and carotenes on experimentally induced septicemia in calves by assessing the immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and antiseptic effects of the herbal compounds.

MATERIAL AND METHODSStudy design and model induction

Ten Holstein-Frisian bull calves, 8-10 days of age, with body weight 50±5 kg, were continuously fed with colostrum. They were categorized into two groups: Control group (experimental septicemia + antibiotic therapy + placebo) and Treatment group (experimental septicemia + antibiotic therapy + formulated drug). The clinical signs and clinical scores were recorded on the entrance day, 5 days after that (adaptation period), and the day before starting the experiment (

26). The

E. coli strain of O111:H8 was chosen in the present study because it is easily available and is rapidly phagocytized, thus initiating a robust oxidative burst.

Septicemia was induced by a suspension of

E. coli (1.5×10

9 CFU) in 5 mL isotonic saline, which was administrated as a bolus by intravenous route via the jugular vein. The challenge dose was prepared about one hour before the experiment’s beginning. The concentration was checked with a spectrophotometer. For ethical reasons, the calves from the control were treated with a suitable antibiotic selected by antibiogram (

27).

All experimental procedures followed the guidelines on ethical standards for experimental processes in animals, according to the protocol approved by the Animal Ethics Committee, University of Tehran, Iran (Code No: 7508007/6/18).

Treatment with Ceftiofur Sodium (Ceftiprin® 4 gr vial by Nasr Pharma Co) was started 24 h after initiating the

E. coli septicemia, in a dose of 1 mg/kg (intravenous-iv), every 24 h for 3 days in both groups. Calves in the treatment group received a formulated natural-based drug (Rose Pharmed. Co. 6 mL vial), with a treatment interval of 24 h for 5 days in a dose of 5.56 mg/kg BW in 250-300 mL dextrose (5%). The product comprised extracts from

Rosa canina,

Urtica dioica (nettle),

Tanacetum vulgare (tansy), selenium, flavonoids, and carotenes. Each liter of the Urtica/Rosa and Tanacetum/Rosa extracts was supplemented with 16 mg of selenium and 150 mg of urea (US20090208598A1). Rose Pharmed Company provided this formulation for the purposes of this study. Based on the formula below, the drug dose and its treatment interval were calculated by allometric equation from the confirmed dose in humans (5 mg/kg BW) as index species for use in the calf. The control group received 250-300 mL of dextrose 5% as a placebo (

28, 29).

Dose calculation in calf:

MEC = k × weight (kg)

0.75MEC = Minimum Energy Cost

MEC does = treatment dose in index species/MEC in index species

Treatment dose = total dose (Body Weight × Dose mg/kg)

Treatment dose in subject species =

MEC dose (index) × MEC in subject species

K = for mammalian is 70

Treatment interval in calf:

Specific minimum energy cost (SMEC) = k × W (kg)

−0.25SMEC interval in index species =

SMEC in index species × dosing interval in index species

Treatment interval in subject species = SMEC interval in

index species/SMEC in subject species

Blood culture and samplingBlood culture was prepared with a specific diphasic blood-agar media (5% blood obtained from sheep) at 0 h, 8, 15, 24, 48, and 72 h after the

E. coli injection in order to confirm the presence of the presence of

E. coli O111:H8. Additionally, a serotyping was performed on isolated bacteria in the blood cultures (

30).

Clinical symptoms were assessed in 30-minute intervals. Blood samples were collected in sterile tubes to determine TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-ϒ, total antioxidant capacity (TAC), CD4

+ lymphocyte, BUN, creatinine, and glucose before and after the challenge until 6 days. The plasma concentrations of IFN-ϒ, IL-6, and TNF-α were measured by ELISA kits (Bio-Rad Company, UK) and Vet Set kit (Kingfisher Biotech INC, USA), respectively (

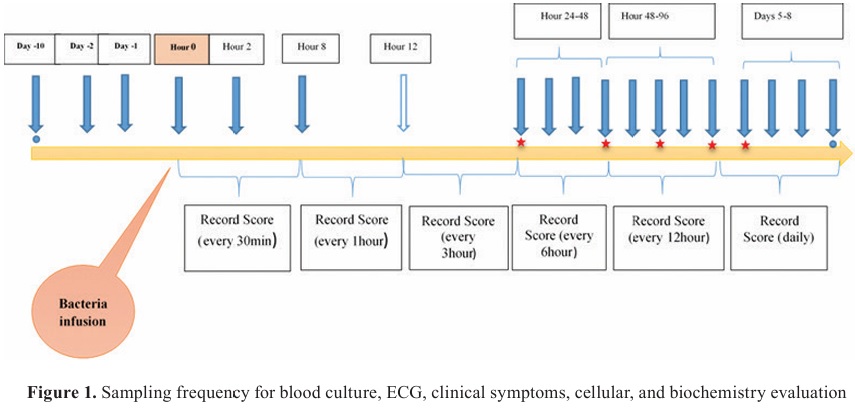

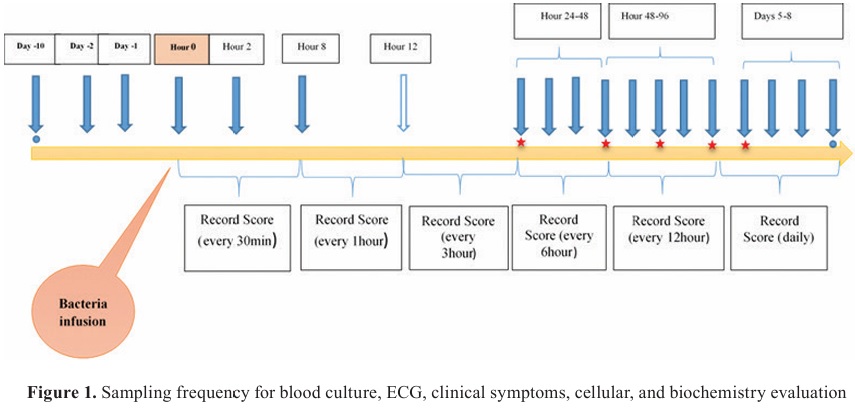

Fig. 1).

Biochemistry factors and cellular immunity evaluation

Biochemistry factors and cellular immunity evaluationTAC was evaluated by Fluorescence recovery after the photobleaching (FRAP) method. BUN, creatinine, and glucose were assessed using an autoanalyzer (ProM/EL 200) in the Veterinary Research and Teaching Hospital of the University of Tehran (VRTH) laboratory. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatine kinase (CK), and myocardial originating creatine kinase (CK - mb) enzyme levels were measured spectrophotometrically with commercial test kits. Cardiac Troponin I (cTp-I) was measured with a Monoband ELISA kit (Accu Bind CAS No=92630).

CD4

+ lymphocyte count of whole blood containing EDTA was measured with Flow cytometry (Partec GmbH, Germany).

Evaluation of electrocardiogram (ECG)A base apex bipolar lead was used to record the ECG. The ECGs were obtained on a single channel system (Model: Cardisuny 501 B1, Fukuda Japan) with 25 mm/s speed and 10 mm calibration equal to 10 mV.

Statistical analysisThe data were analyzed with repeated measures ANOVA using SPSS version 21 software, and the significance level was set at p<0.05. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the data. To evaluate the effect of treatment on serum contents between two groups, the data were analyzed via independent t-test and Tukey. The correlation between arrhythmia and cTnI concentration was expressed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The data were reported as mean ±SD, and the graphs were plotted using Graph Pad Prism 5.04 software. Paired-T test and Tukey test were used to compare the means between control and treatment groups (p<0.05). The asterisks indicate the level of the significant differences *(p<0.05), **(p<0.01), and ***(p<0.001).

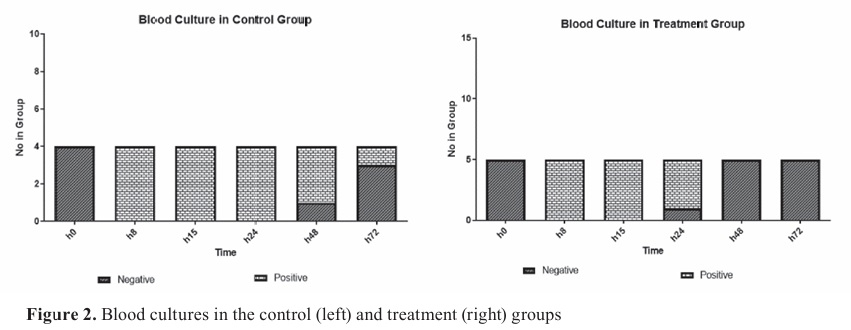

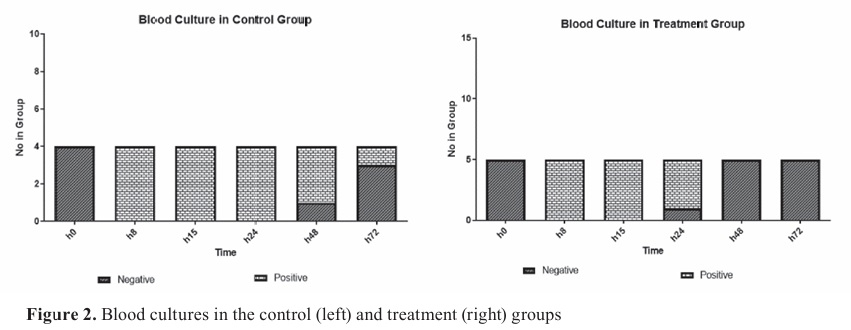

RESULTSBlood cultureThe blood culture results showed that bacteria were detected in two experimental groups 24 h after the challenge. However, the blood cultures were negative in the treatment group at 48 and 72 h, compared to the control group (

Fig. 2).

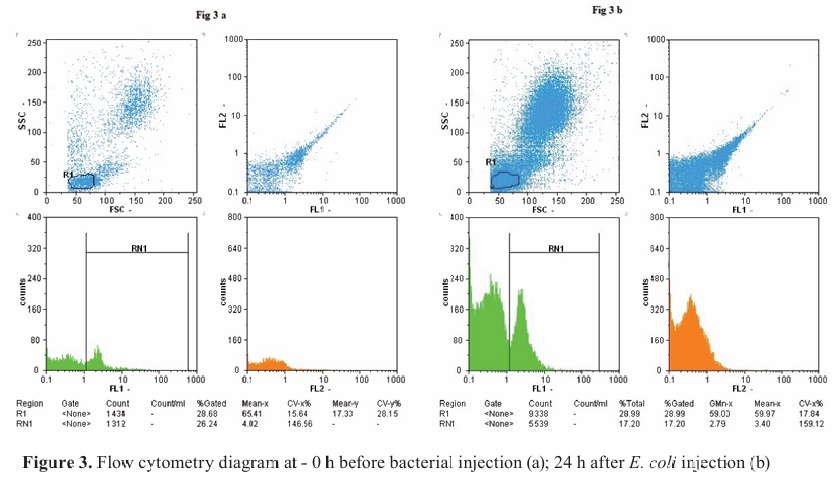

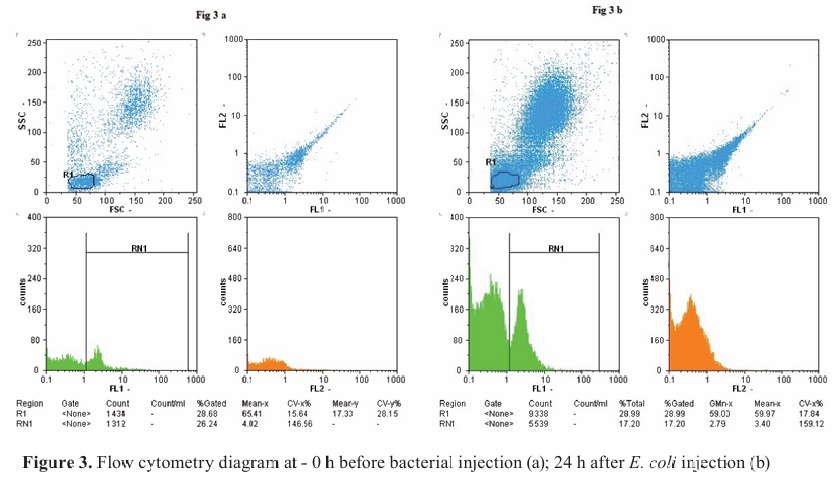

CD4+ lymphocyte countFlow cytometry revealed a decrease in CD4

+ lymphocyte counts, leading to septicemia. After 24 h, the cell count reached a minimum level in both groups, with no statistical significance (

Fig. 3a, b). At the end of the study, the treatment group showed an increase in CD4

+ counts compared to the control group, but this difference was not statistically significant.

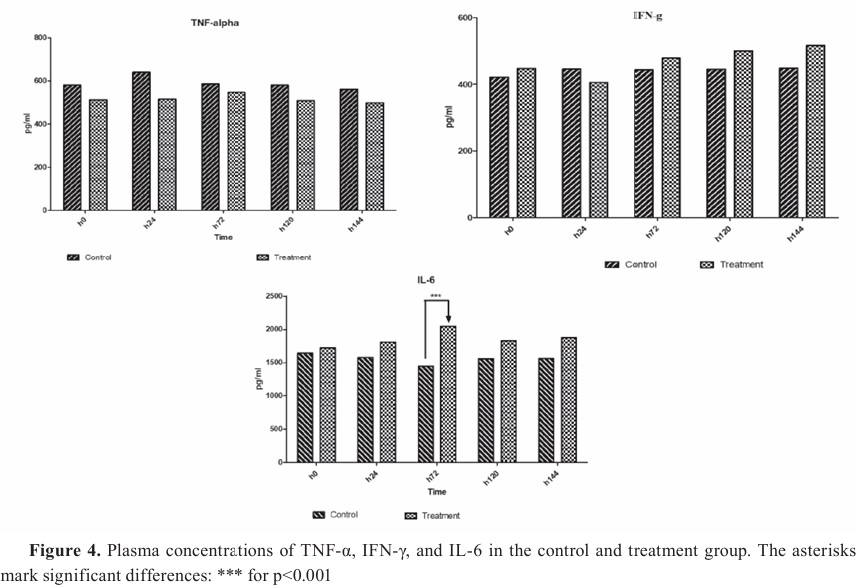

Cytokines evaluation

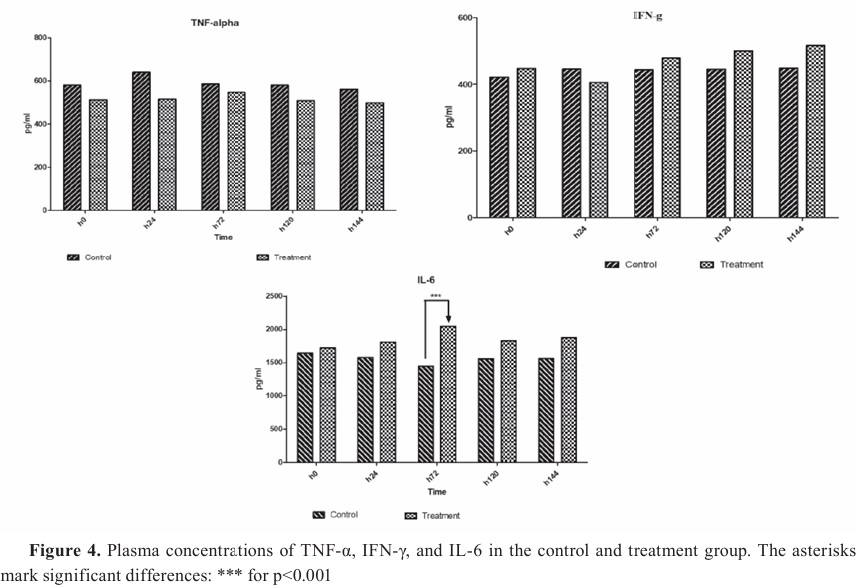

Cytokines evaluationThe maximum plasma TNF-α concentration occurred 24 h after the challenge in the control group. Nevertheless, in the treatment group, the level of plasma TNF-α during the study was lower than in the other group (

Fig. 4). Still, this alteration was not statistically significant in the two groups during the study period. Based on the results, the IFN-γ serum level decreased 24 h after the challenge, but increased after 72 h and remained steady until the end of the study in both groups. Nevertheless, this enhancement in the formulated treatment group was higher than the other, but these changes in the two groups were not statistically significant. The IL-6 levels reduced after the challenge but they were not statistically significant in both groups during the survey. However, after prescribing a formulated drug, the serum level of IL-6 increased, and a significant difference was observed between the two groups at 72 h (p=0.0014).

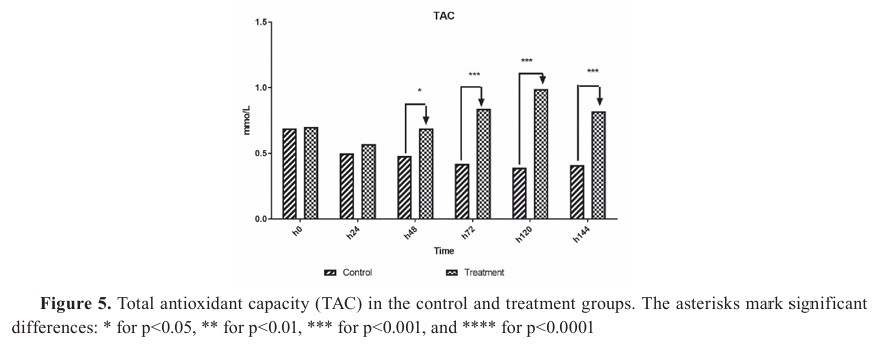

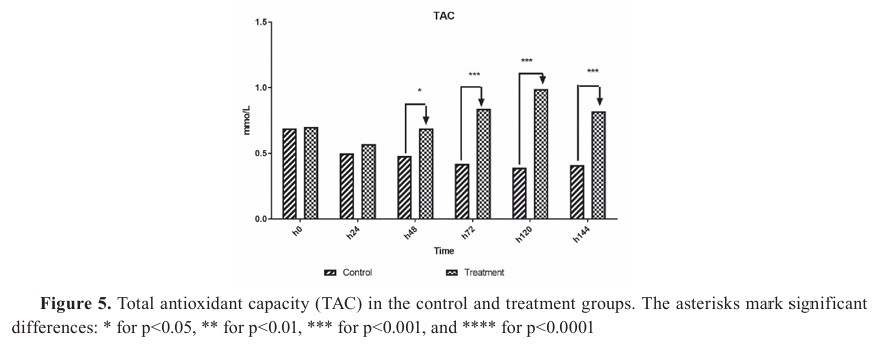

Biochemistry factorsSignificant decrease of TAC was observed in both groups 24 h after the initiation of the challenge and treatment (p=0.04). However, the treatment group showed a sharp increase in TAC after 48 h, which was statistically significant compared to the control group (p=0.032). Significant difference was observed in TAC at 48 h (p=0.02), 72 h, 96 h, and 120 h (p=0.001) (

Fig. 5).

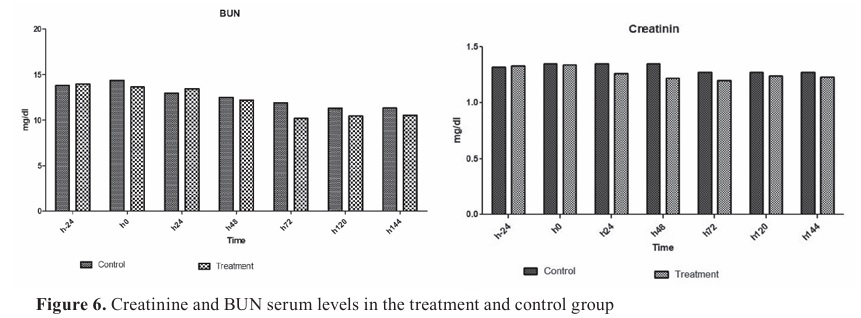

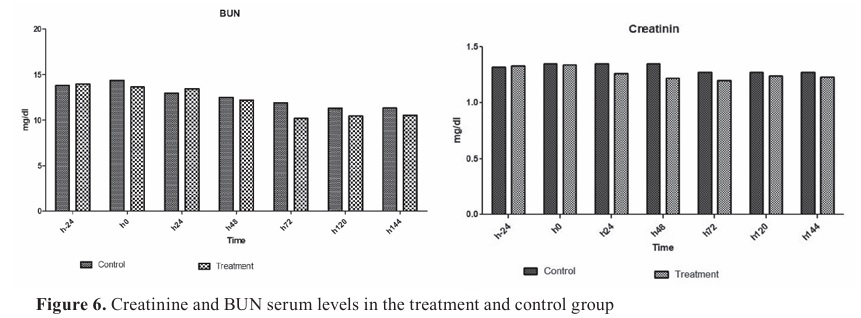

Serum creatinine and BUN levels remained normal during the experimental septicemia (

Fig. 6). Serum creatinine and BUN levels reached the lowest level in the treatment group at 72 h, but the difference was non-significant. Blood glucose levels in the treatment group were lower than in the control until day 5, but the difference was negligible (p>0.05).

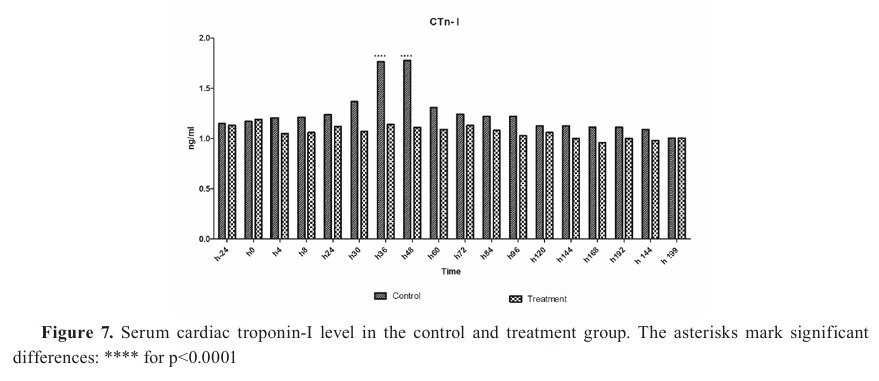

ECG enterprises and cardiac enzymes

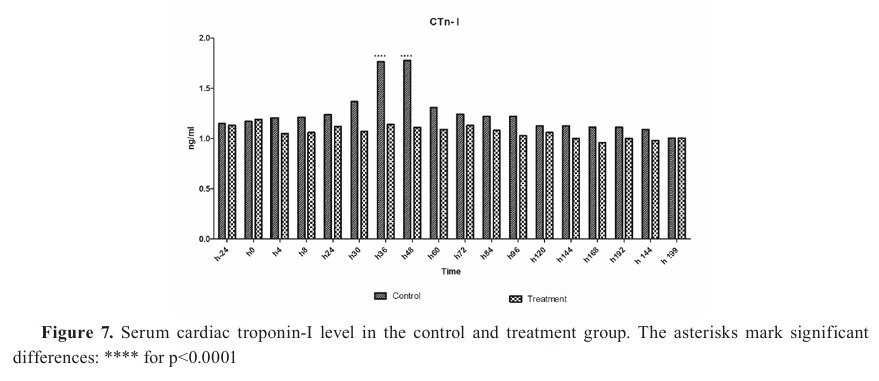

ECG enterprises and cardiac enzymesThe cTp-I was higher in the control group in all periods, with significantly higher levels at 36 and 48 h compared to the treatment group (p<0.001) (

Fig. 7). The cTp-I levels were equalized at 199 h of the treatment.

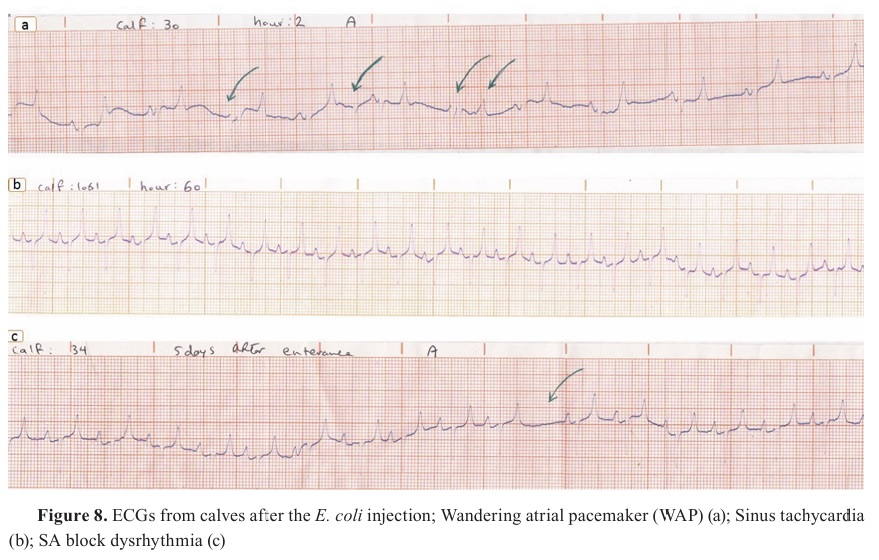

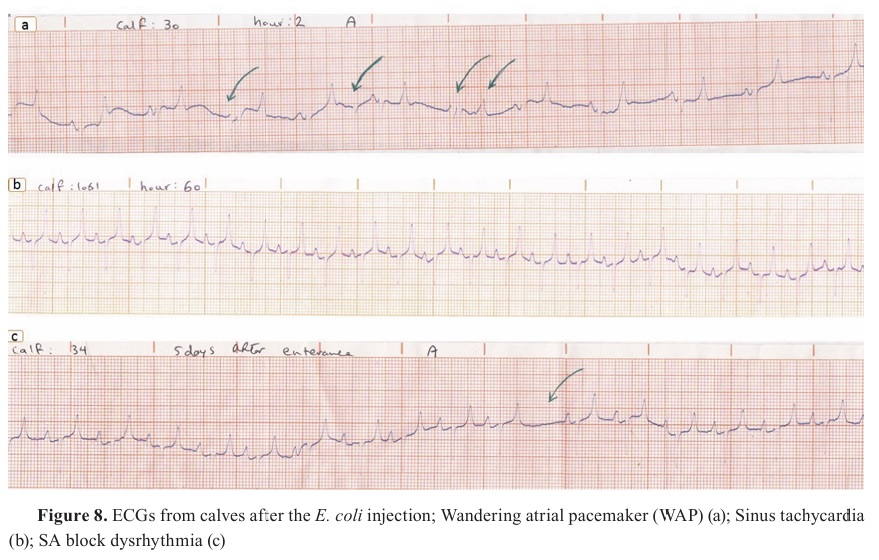

The maximum rates of dysrhythmias were recorded between 8 h and 36 h in 44-55% of the calves. The most observed dysrhythmias in the two experimental groups were sinus tachycardia (6/10) (

Fig. 8 b), wandering pacemaker (6/10) (

Fig. 8 a), SA block (5/10) (

Fig. 8 c), sinus arrhythmia (4/10), and AV blocks. However, despite that the maximum levels of cTp-I were recorded in these periods, a significant correlation was not found between arrhythmia occurrence and cTp-I.

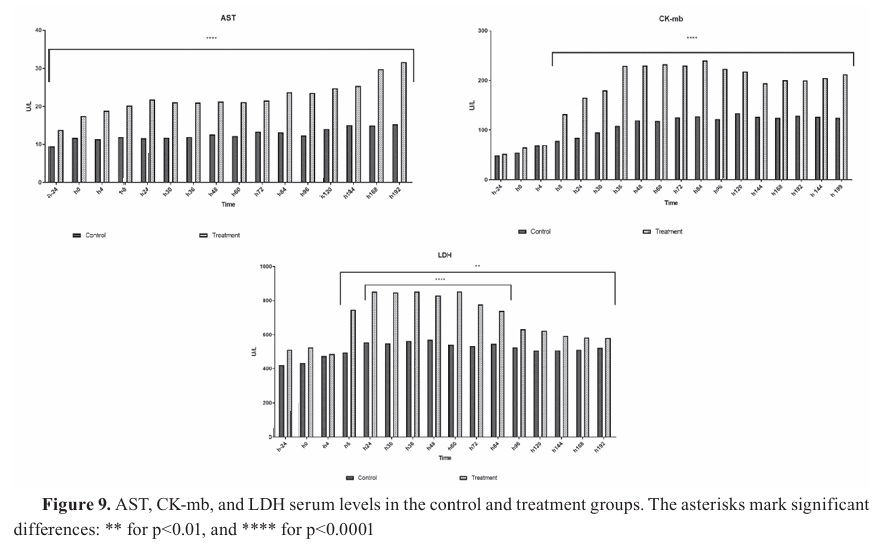

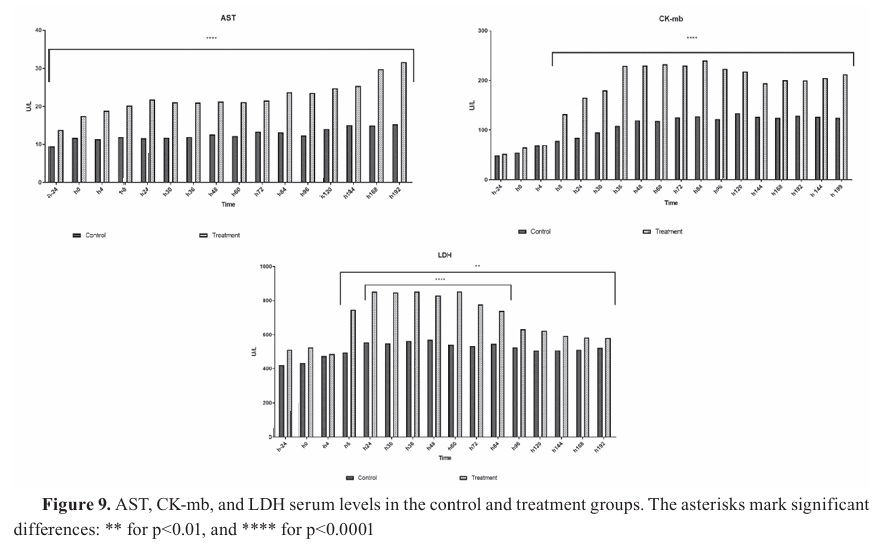

The AST concentration before in the experimental group was 17.51 IU/L before the experimental sepsis, and had significantly higher values compared to the control throughout the other periods of the study (p<0.0001) (

Fig. 9 - AST). A negative correlation was observed between ECG changes with the higher AST levels (r=0.69, p=0.038).

CK-mb enzymes have increased at 8 h of the experimental sepsis in both groups and remained this trend until the end of the study. Significantly higher values for this period were observed in the experimental group (p<0.0001) (

Fig. 9 - CK-mb).

LDH levels have significantly increased 24 h after the experimental sepsis initiation and were significantly higher in the treatment group, peaking at 853 IU/L. This concentration has declined at 96 h until the end of the study. The differences between the two groups were statistically significant (p<0.0001). However, the changes in enzyme over time were significant (p<0.05), and a positive correlation was observed between the peaks of occurrence of the ECG changes and the highest level of LDH (p<0.0001) (

Fig. 9 - LDH).

DISCUSSIONThe study aimed to determine the effects of intravenously administered herbal formulation on multiple serum indices in calves with experimentally induced septicemia by

Escherichia coli strain O111:H8. This included monitoring various health parameters and comparing the effects on the treatment group that received the herbal formulation with the control that was administered with a placebo intravenous solution. Based on the obtained results, the treatment group had an increase in CD4

+ lymphocyte counts compared to the control, although this difference was not statistically significant. This suggests a potential enhancement in immune function due to the herbal treatment. cTP-I levels decreased in the treatment group, indicating improved cardiac function. Additionally, LDH levels changed significantly over time with a positive correlation observed between ECG changes and the peak LDH levels, suggesting that the herbal drug may help monitor cardiac health during sepsis. Serum creatinine and BUN levels remained normal throughout the experimental septicemia. The herbal formulation led to an increase in total antioxidant capacity, indicating a potential protective effect against oxidative stress during septicemia. These results suggest that the herbal based drug has beneficial effects on the immune response, cardiac function, and overall health in calves with septicemia, supporting its potential use in veterinary practices for managing severe sepsis. These aims highlight the comprehensive approach taken by the researchers to evaluate the potential benefits of the herbal-based drug in treating severe sepsis in calves.

According to published articles, the high prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in dairy farms against

E. coli was due to unrestricted human and veterinary use of antimicrobial agents (

31). Natural (herbal) immunomodulatory drugs can be helpful for veterinarians and practitioners in addressing issues on industrial farms and reducing antibiotic use.

The incidence of sepsis in calves is high due to consumption of inadequate colostrum. Despite the regular antibiotic use, there is still high mortality associated with sepsis and septic shock (

32). A recent research has revealed that bacterial antigens cause a cascade of cellular mediators or cytokine production. Several research studies have illustrated that TNF is the primary mediator of the sepsis and septic shock inflammatory response. Herbal formulation components, such as

Urtica dioica leaf extract, may lower TNF-α and potent pro-inflammatory cytokines which are elevated by bacterial presence. Furthermore, the

Tanacetum vulgare extract has antioxidant and anti inflammatory properties recognized in traditional medicine (

33).

IL-6 is formed by various cells, especially macrophages, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, and endothelial cells, in response to exogenous LPS and some cytokines (IL-1 and TNF-α). Increased IL-6 concentrations can be found during multiple acute conditions, such as major surgical procedures and sepsis, with peak values following the increment of TNF-α and IL-1 (

31). IL-6 has pro-inflammatory properties but can also aid in anti-inflammatory responses. It can inhibit the release of TNF-α and IL-1. IL-6 levels have increased in the treatment group after 72 h, thus followed by decreased TNF-α levels. IFN-ϒ is a crucial cytokine for innate and adaptive immune responses and has antimicrobial properties. Higher IFN levels in the treatment group were indicative of successful sepsis treatment and were correlated with improvement of the symptoms (

34).

Rosacanica extract has various antioxidants and bioactive components which have anti inflammatory and a free-radical-scavenger properties (

33, 35). The effect of IMOD (natural medicine that consists of a mixture of herbal extracts) on the treatment of oxidative stress related disorders and immune-inflammatory-based diseases like type-1 diabetes, colitis, and polycystic ovary syndrome (POC), has been demonstrated in previous studies (

36, 37). The serum level of IL-6 and IFN-ϒ in the treatment group was non significantly increased, whereas the concentration of TNF-α was non-significantly decreased, which is consistent with previous studies (

38). Previous studies on the effects of

R. canina fruit as an adjuvant therapeutic for managing inflammation related diseases, particularly in preventing UTIs in women after cesarean sections, showed its anti-inflammatory properties (

39).

Basoglue et al. reported that calves with septicemia and diarrhea had non-significantly increased plasma creatinine level compared with the control (healthy) (

40). Unlike some earlier studies that reported a significant increase in the plasma creatinine levels during septicemia, this study reports normal creatinine levels in the treatment group and lower in the control (

41). The treatment group showed increased total antioxidant capacity levels. Other researchers confirmed that TAC remained constant in aseptic patients who received the formulated drug compared to the control (

42). The extract of

Rosa canica and

Tanacetum vulgare contains various antioxidant components, including vitamins C and E, flavonoids, and bioactive like phenolics, carotenoids, anthocyanins, and tannins, which all exhibit free radical scavenging effects (

31, 33). These effects have been demonstrated by increased cellular antioxidant reserves in patients (

43).

Hyperglycemia is a significant metabolic disorder during septicemia and can be associated with a high mortality rate (

44). Blood glucose level in the treatment group was non-significantly lower than the control. Based on the results obtained by previous studies, drugs administration could increase insulin secretion in rats (

36). According to this hypothesis, the lower serum glucose level in the treatment group compared to the control may be due to the higher insulin secretion (

37).

The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of formulated herbal drugs have been demonstrated in AIDS patients based on the lower TNF-α levels and higher CD4

+ lymphocyte number in the treatment group (

36). However, in the present study, CD4

+ lymphocyte number was not increased in the treatment group. In HIV-positive patients, herbal drug injection enhanced CD4

+ lymphocyte number 1–3 months after the treatment (

38). The drug’s effectiveness on CD4

+ lymphocyte count in this study may be due to its short-term administration (5 days).

On the other hand, as an excipient in formulated drugs, selenium is an important element in mammals’ immune systems and has antioxidant capacity. It seems that the formulated drug’s antioxidant effect contributes with a decrease in pathological damage during tissue and cellular stress. Consequently, it improves cellular function and the overall defense system of the body (

45). Information on TAC evaluation in ruminants, particularly cattle, is limited; however, the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of viral diarrhea and respiratory diseases has been explored (

46).

One of the best ways to measure and diagnose abnormal heart rhythm is ECG, particularly when pathogens damage the conductive tissue. A considerable amount of literature has been published on the effects of sepsis on the cardiovascular system, stating therein that 50% of clinical cases with sepsis and cardiovascular damage, have a positive association (

47).

Early detection of heart disorders is an independent prognostic factor that can provide appropriate treatment and enhance the recovery rate. cTp-I is released from damaged myocardial cells into the bloodstream and reaches its maximum level in about two days. High levels of this protein in the blood can be detected, typically occurring 12 to 24 h after the onset of heart damage (

48). Dysrhythmia and increased cTp-I during the experimental sepsis of the current study were positive confirmation for the impact of the sepsis on the cardiovascular system. However, the incidence of dysrhythmia and cTp-I decreased after the treatment.

The blood culture was negative after 48 h in the treatment group which was a positive indication of the antimicrobial activity of the herbal formulation. Additionally, therapeutic effects were observed on the renal and cardiac function as well. Immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and anti inflammatory effects on the sepsis was observed by down-regulating cytokines and activating antioxidant factors. These results indicate that the herbal-based drug may be beneficial in the treatment of severe sepsis in calves. However, further research is needed to confirm these findings and assess their clinical significance.

CONCLUSIONRe-emerging viral and bacterial diseases are increasingly impacting the immune system and causing long-term effects. The herbal formulation containing

Rosa canina,

Urtica dioica, and

Tanacetum vulgare demonstrated beneficial effects on renal and cardiac function in calves with septicemia. It reduced serum TNF-α levels associated with inflammation, while IL-6 and IFN-γ levels were higher compared to the control group. This suggests that the herbal formulation may have immunomodulatory properties that can aid the inflammatory response during sepsis. These results support the use of this herbal treatment as an adjunct in veterinary medicine for septicemia in calves, highlighting the benefits of plant based medicines for their immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial conflict of interest regarding authorship and publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe article’s authors would like to thank Rose Pharmed Company for the gift of formulated drugs and the financial support of the Biomedical Research Institute, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, and University of Tehran.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONMHSh took part in conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, acquisition of resources and data curation. ZE was involved in conceptualization methodology, acquisition of resources and supervision. MMD and SL made the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, acquisition of resources, data curation, supervision and project administration. SHA participated in methodology, validation, formal analysis and data curation. All authors were involved in writing and editing of the manuscript.

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0018

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0018