Regular monitoring of susceptible animal species for specific antibodies is essential to achieve or to maintain disease free status for a country. The absence of certain disease in a country for many decades would yield expectation that collected animal serums would be negative for the presence of specific antibodies. However, large-scale tests often dismiss single reactor findings as poor sample quality. The current study aimed to investigate the effect of storage conditions of negative serum samples and the specificity of ELISA kits on the test results, focusing on two key livestock diseases: foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) and peste des petits ruminants (PPR). Serum samples from bovine and ovine sources were stored at varying temperatures and durations, were subjected to freeze-thaw cycles, and were retested. Results were compared with zero-day tests which were considered to be truly accurate and negative. The quality of ELISA test results is less significantly affected by serum samples quality (affected by temperature, storage time, and freeze-thaw cycles) and occurrence of false positive single reactors, than the diagnostic specificity of different ELISA lots. This study challenges the conventional justification for single-reactor findings and underscores the importance of ELISA kit quality.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is nowadays the most common technique used in veterinary medicine to determine the presence of antibodies for certain diseases in animal serum. It is based on the specific antibody-antigen link tailored with enzyme reaction to detect and quantify the immunologic reaction. Though commercially available, ELISA kits undergo a thorough optimization, validation, and standardization process (

1) before market authorization. Despite this, unexpected results can still occur. Thus, ELISA kits should be chosen according to the purpose, with primarily high diagnostic sensitivity (Dse) or diagnostic specificity (Dsp). For instance, an ELISA kit of high Dsp should be used for disease-free status. On the contrary, high Dse tests should be selected to re-establish free status. While false negative outcomes may result from the long sample storage time (

2), false positive reactions usually occur due to the cross-reactivity and non-specific bindings (

1) or hemolysis (

3). The cross-reactions usually occur between related pathogens such as

Mycobacterium bovis and

Mycobacterium paratuberculosis (

4) or between members of the

Morbillivirus genus (

5). Furthermore, the proteolysis, as well as natural and reversible immunoglobulin aggregation of long stored serum samples under different temperature conditions, are known factors altering the antibody stability and, consequently, the immune complex formation, which is the base principle of ELISA (

6).

Large-scale surveillance usually includes sampling on daily basis, where storage is often unconditional, particularly in developing countries. On average, veterinarians submit the collected samples after 3.2 days, and in rare cases, even after 21 days (

2). Retrospective analysis (

7) of samples from the national banks is often required in epidemiology, presuming the interpretation (

8) of results on a sample of potentially impaired quality due to the number of freezing-thawing cycles. Thus, serum samples that have undergone more than five cycles are not recommended to be used (

9), as well as sera of turbidity level 3 measured by McFarland standard set (produced by HIMEDIA, India).

Though many variables can cause false results, the main aim of this study was to supplement the scientific knowledge on the impact of serum sample quality and Dsp of the ELISA kits on the accuracy results, including the freeze-thaw cycle, storage time, and temperature of samples. The ELISA test for foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) and peste des petits ruminants (PPR) were selected for this investigation because Serbia is free from these diseases for decades. Our initial hypothesis was that the conditions of sample storage and treatment may affect the results of the ELISA test.

MATERIAL AND METHODSWork with animalsForty blood samples from cattle and forty sheep blood samples were used to evaluate the storage temperature and duration impact on ELISA results. The samples were collected under the national surveillance program for eradication of brucellosis, bovine enzootic leucosis and foot and mouth disease.

Time schedule and temperature treatment of the serumImmediately after coagulation (day zero), 40 cattle serum samples were tested for presence of non-structural proteins (NSP) FMD virus antibodies and 40 sheep sera for the presence of PPR antibodies. Afterwards, half of them (20 sera samples from cattle and 20 from sheep) were left at 4-8 °C, and the second half of sera samples (20 bovine and 20 ovine serum samples) were stored at 22-25 °C in the original vacutainers. All samples were subsequently tested on days 7, 14, and 21. In case of positive results, samples were retested after the treatment at 56 °C for 30 min. During each subsequent run, a volume of the serum was taken and frozen at -80 °C. Frozen samples were tested after three months. The storage test was performed so that real-field conditions could be checked on the ELISA results.

Ethical approvalThis article does not include methods performed by the authors involving animals. All samples were obtained and analyzed at the Scientific Institute of Veterinary Medicine of Serbia, which is also the national reference laboratory for PPR and FMD. The Scientific Institute of Veterinary Medicine of Serbia is authorized to use the data for scientific and publishing purposes.

ELISAsFor FMD testing, two lots of commercial ELISA kit ID Screen® FMD NSP Competition test were used following the manufacturer’s instructions (lots: I26 and J80). For PPR, two lots of ID Screen® PPR Competition tests were used per the manufacturer’s recommendation (lots I28 and K09).

Assessment of serum turbidity and hemolysisThe change in visual sample quality was evaluated during the experiment. The appearance of turbidity was evaluated by comparison with the McFarland standards “McFarland standard test” manufactured by HIMEDIA Laboratories Pvt. Ltd (India). The appearance of hemolysis in the serum was determined by visual examination.

Statistical analysisSince Serbia is free of FMD and PPR for quite a long time, all bovine and ovine sera were considered true negative. A doubtful sample result was considered positive when calculating the Dse. Diagnostic specificity was calculated according to Van Stralen et al. (

10). The specificity of the test was calculated as TN/(TN+FP), where TN is a number of truly negative samples and FP is a number of false positive samples. We assumed that all samples are negative as they were in the initial test. The positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) as well as Number of false positives to a test and Probability of false positives were calculated using Epitools (

11) for a 5% probability of infection.

RESULTS Visual changes in samplesThe samples stored at 4-8 °C showed no visual changes in sample quality during the experiment, regardless of the species. All serum samples remained clear and with no turbidity, hemolysis, or change in smell. However, samples stored at 22-25 °C after two weeks became opalescent to the level of turbidity of the McFarland standard 2, with an unpleasant odor due to decomposition products. Until 21

th day of storage at room temperature, most serum samples showed the increased turbidity of the McFarland 4 level and the appearance of an intense, unpleasant odor.

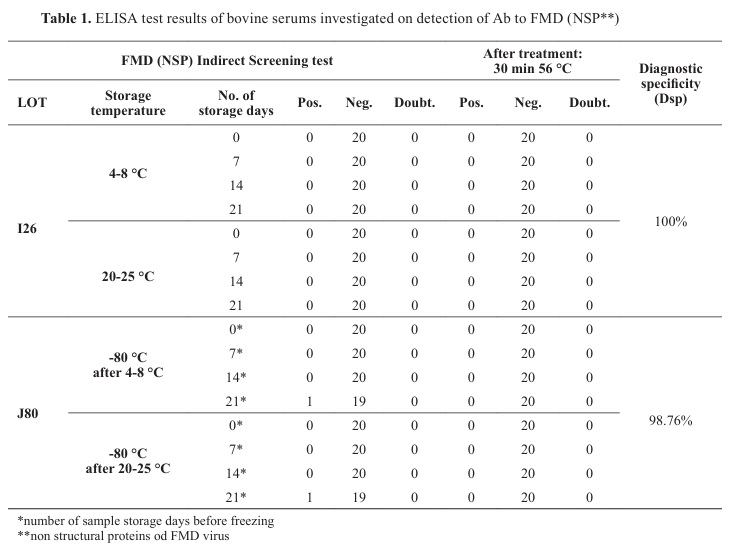

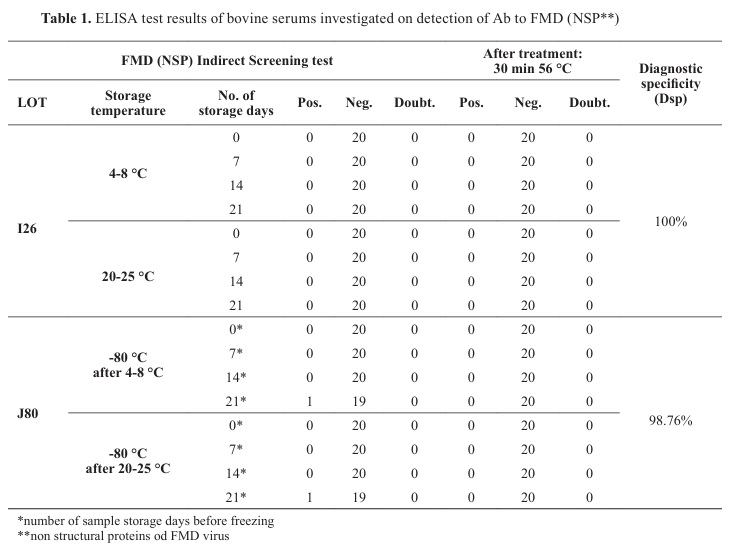

NSP FMD ELISA resultsBy testing 40 bovine sera stored at 4-8 °C, 22-25 °C and -80 °C for NSP FMD antibodies on zero-day, 7

th, 14

th, and 21

st day, consistent negative results were obtained for 38 samples. Two sera frozen on the 21

st day (one sample was stored at 4-8 °C and the other at 22-25 °C before freezing) showed positive results after thawing. After the incubation at 56 °C for 30 min, both sera gave negative results (

Table 1). Thawed sera were tested with different lots of ELISA kits (lot J80). The first used Elisa kit lot: I26 had diagnostic specificity 100%, but the second lot J80, had diagnostic specificity 98.67%, positive predictive value (PPV) 1 and negative predictive value (NPV) 0.9494 for a 5% probability of infection. The number of false positives could be max 9 and probability for 2 false positives samples was 0.2724 for lot J80.

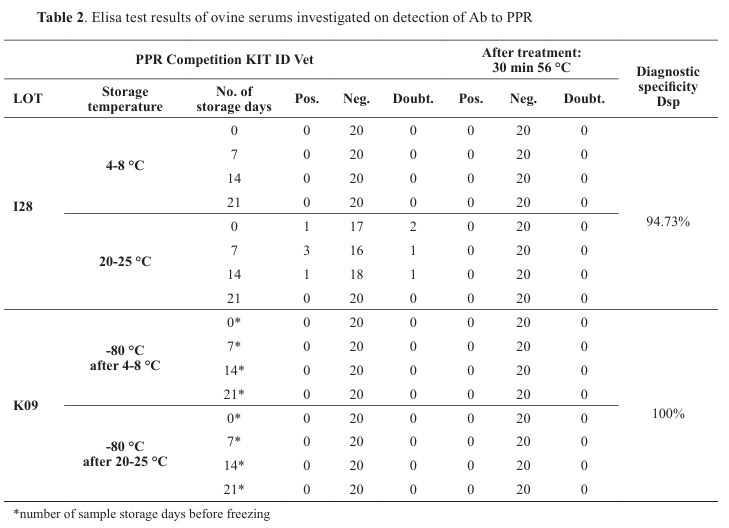

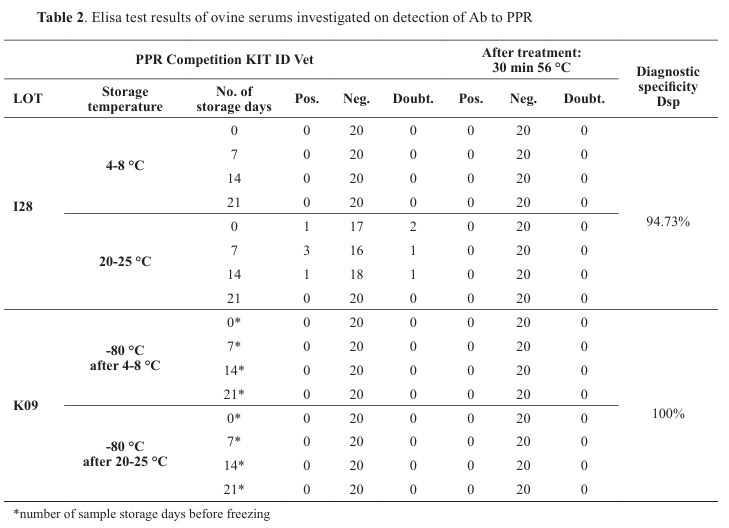

PPR ELISA resultsBy testing 40 sheep sera for the PPR antibodies presence on the zero-day, two doubtful and one positive sample were detected (

Table 2). However, after the inactivation, all turned to negative results. On day 7, three positive samples, which were positive and doubtful at day zero, and one doubtful result, were obtained. Again, after inactivation, all four samples reacted negatively. The same results were obtained after 14 days of storage. On day 21, all samples were negative, using the same ELISA lot I28. After three months, all previously frozen and thawed samples were negative using another lot K09 for PPR. Diagnostic specificity (Dsp) for lot K09 was 100% but for lot I28 Dpi was 94.73%, PPV and NPV for ELISA kit lot I28 were 0 and 0.9473 for a 5% probability of infection. A number of false positives results with lot I28 should be max 23 and probability for 9 false positives samples as we got was 0.1330.

DISCUSSION

The results showed variation when using different lots of ELISA kits for FMD and PPR. The Dsp between the ELISA kits used for PPR varied by 5.67%, while between kits used for FMD NSP diagnostics, it varied by 1.24%. After treatment of a sample of disputed sera for 30 min at 56 °C, there was no difference in diagnostic specificity between the kits.

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of different serum storage conditions on the ELISA results and occurrence of false positive results. When dealing with transboundary diseases (TADs) like FMD and PPR, and conducting extensive sample testing to uphold a country’s disease-free status, interpreting positive samples poses a persistent challenge. These samples are typically sourced from serum banks, and obtaining resamples from specific animals can be impractical. The standard approach when questioning a potential false positive result is to conduct a retest. If the result remains positive unexpectedly, it is advisable to proceed with resampling. Nevertheless, considering the results obtained and acknowledging the imperfections of the test, the samples under scrutiny should undergo testing with a different test batch. When assessing bovine serum samples for the presence of FMD NSP antibodies, stored for varying durations at different temperatures, batch J80 exhibited a diagnostic specificity of 98.76%, whereas batch I26 demonstrated a diagnostic specificity of 100%, assuming negative outcomes due to the country’s FMD-free status. Following a 30-minute treatment of positive samples at 56 °C, all sera yielded negative results. Likewise, the results obtained for PPR antibody detection revealed variations in the performances of ELISA batches. Batch I28 showed an estimated Dsp of 94.7%, whereas batch K09 exhibited a Dsp of 100%. Nevertheless, following heat treatment, the retesting of positive and doubtful serum samples yielded negative results. The findings showed that complement inactivation not only did not impair antibody detection but also improved specificity (

12). Therefore, the findings indicate that the quality of the tests plays a more crucial role in producing false results than the quality of the samples themselves. These findings align with the outcomes of Xiumei et al. (

13), demonstrating that subjecting serum to a 56 °C treatment for 30 min deactivates the complement, diminishes the ELISA test background, and thereby prevents false positive reactions. Furthermore, despite the samples in this study undergoing one freezing-thawing cycle, several studies have indicated that it does not impact the ELISA results. According to Michaut et al. (

14) 3-12 freeze-thaw cycles are not affecting ELISA results, while Pnsky et al. (

15), Shurrab et al. (

16), and Cuhadar et al. (

17) confirmed that ten-fold freeze-thaw cycles did not affect results of total protein, albumins, or immunoglobulins. Torelli et al. (

18) confirmed that even 14 freeze/thaw cycles did not affect stability of antibodies against Influenza virus in serum. Taking into account the storage duration, our study demonstrated that no alterations leading to false positive results occurred during the 21 days at both 2-8 °C and 20-25 °C, as well as after three months of freezing. Cliquet et al. (

19) demonstrated that even in cases of highly contaminated samples of serum or body fluids, there is no significant impact on the results of the ELISA test. In a group of truly negative samples any positive result must be false as it is the case in our experiment. Nonetheless, when considering the potential for false negative results in the truly positive samples, it is essential to underscore that distinct classes of immunoglobulins may vary in susceptibility to degradation, depending on the storage conditions. Johnson et al. (

20) suggested different condition for storage of polyclonal or monoclonal serum antibodies and suggested lyophilization and storage on -20 °C for a long-time stability. Huang et al. (

21) confirmed that IgE is incredibly stable more than 90 days on room temperature and after 10 freeze/thaw cycles while Ostergard et al. (

22) said that IgE is stable 4 8 weeks at on -20 °C and at least 48 h at room temperature. Consequently, some authors like Cray et al. (

23) suggest using samples storage up to 30 days at -20 °C with one freezing and thawing cycle for immunological assays, while Castro et al. (

24) confirmed stability of IgG and IgM up to 30 days and after repeated freezing/thawing cycles.

CONCLUSIONThe presented results confirm that the lack of adequate sampling and storaging conditions does not affect the results of the ELISA analysis for FMD and PPR while the diagnostic specificity of the ELISA lot reagents themselves could be responsible for the affected test results.

Serum samples stored at 4-8 °C and 20-25 °C for up to 21 days, as well as frozen serum samples for up to 3 months at -80 °C, did not exert a significant impact on ELISA results for NSP FMD and PPR. Despite the occurrence of proteolysis and microbial contamination in sera during the 21 days of storage, there was no discernible effect on the final results in the ELISAs. Notably, all positive and doubtful samples, when retested after subsequent heat treatment at 56 °C for 30 min, yielded negative results. The variation in ELISA batch quality was apparent for both FMD and PPR kits. Variations in diagnostic specificity may be responsible for the occurrence of single reactors in extensive monitoring.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTThe authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial conflict of interest regarding authorship and publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis research was funded by the Serbian Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation, with grant number 451-03-66/2024-03/200030.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONLV has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, as well as the analysis and interpretation of the data. DG participated in the study design, performed statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript. SS and ZZS conducted the immunoassays ELISA tests. VM has been revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. They have also given final approval for the version to be published.

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0019

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0019