The present study aimed to explore the connection between the acoustic parameters of dog sounds and the morphometric characteristics of the laryngeal cartilages in dogs with various body sizes. We compared the measurements of the laryngeal cartilages (n=15) of equal number of small, medium, and large size dog cadavers with the acoustic parameters recorded from other dogs of similar size and number. The morphometry was performed with a digital caliper. Animal sounds were analysed with Raven Pro 1.6 software. Waveform and spectrogram graphs were displayed for each sound with 512-point Hann window 50% overlap time. Sound selections were manually verified. Our findings confirmed that small-sized dogs generate the highest pitched barks in every measured frequency (5%-95% and peak). In addition, their vocal signals are of the lowest tonality expressed in sound-to-noise ratio (SNR). The Frequency parameters (F) 5%, 25%, and 95% showed significant correlations with the morphometric values of the laryngeal cartilages, which indicates their role in the sound formation. These acoustic parameters had strong to moderate negative correlations with the thyroid cartilage (TC) width and height; arytenoid cartilage (AC) – distance between proc. corniculatus and proc. cuneiformis (corn-cun), depth of ventricle and distance between the two proc. cuneiformis (cun-cun); width, height and depth of cricoid cartilage (CC); width and height of the epiglottis (EP). Our finding suggested that F5%, F25% and F95% can be reliable parameters and can be used in the classification methods of dogs’ sounds as it varies predictably with laryngeal cartilages size.

The canine larynx is a convenient model for studying the general mechanism of vocalization and speech in humans. The characteristics of the dog larynx are of interest are of interest not only to ethologists and veterinary practitioners but also to human medicine because canine and human larynx shares similar characteristics in size and gross structure (

1,

2).

Domestic dogs use barking as one of the primary tools for social interaction with their owners. By contrast, body language and olfaction are used mostly for interaction among conspecifics. These traits are believed to be a result of evolutionary selection and domestication (

3,

4). According to Pongracz et al. (

5), pet dogs use a variety of acoustic signals when communicating with humans compared to stray dogs. On the other hand, their closest relatives, the wolves, bark extremely rarely and in a very limited behavioral context. Wolf cubs, however, use barking for intraspecies communication – during play, expressing behavior for food or for defense (

4). According to Pirrone et al. (

6), season of birth, breed, and sex are related to the speed of sensory maturation and behavioral development in puppies.

Dog barking is acoustically specific for each individual (

7,

8,

9,

10). The length of the vocal folds determines the possible frequency range of sounds that can be generated. From a physical perspective, larger breeds produce lower-frequency sounds than small breeds which have higher pitched barks (

11). Pongrácz et al. (

12) established range of high, medium, and low frequency of barking in dogs - 1,200-1,400, 850-1,050 Hz, and 500-700 Hz, respectively. Farago et al. (

13,

14) demonstrated the growling as an aggressive expression with specific acoustic characteristics in different dog breeds. Sibiryakova et al. (

15) established a negative correlation between the acoustic parameters of dog whining and body size. Other authors claim that growling in large dogs sounds more aggressive than growling in small breeds (

16,

17).

Recent studies about body size-dependent acoustic characteristics of communication signals focused on different sound parameters. Bowling et al. (

11) measured and established the dominant frequency (the frequency at which the highest amplitude is recorded) and the fundamental frequency (the frequency that is generated primarily in the vibration of the vocal cords) in different species of primates and carnivores, determining heterogeneity in vocalization data. In addition to this, Zhang (

18) measured the frequencies and the significance of SPL (sound pressure level) and vocal fold vibration amplitude in men and women, proving that these parameters are sex dependent. Furthermore, Walikar et al. (

19) have measured SNR (sound-to-noise ratio-a parameter that directly correlates with the harshness of the voice), shimmer (variation in frequency from cycle to cycle), and jitter (same as shimmer but in relation to amplitude) in people with different pathologies of the larynx, showing that any change in vocal folds directly reflects the amplitude and frequency of the generated sound.

The sound characteristics of barking have been studied in detail by a number of scientists (

3,

4,

20,

21) so as the differences in the anatomical structure of the larynx and the vocal apparatus as a whole (

22). There is however limited scientific data on the relationship between the morphometric parameters of the laryngeal cartilages and the acoustic characteristics in dogs with various size.

Our study aimed to investigate specific morphometric features, beyond overall animal size, that might influence the frequency distribution of generated sound expressed by frequency percentiles. There is limited research on the correlation between laryngeal cartilage size and specific percentiles in dog vocalizations. While we acknowledge the established relationship, our study delves deeper into how specific laryngeal cartilage dimensions might modulate the sound pitch. We hypothesized that variations in cartilage shape and proportion, even within similar overall larynx sizes, could influence vocal fold tension and, consequently, frequency.

MATERIAL AND METHODSMaterials

Dog cadavers (n=15) preserved in formaldehyde, used as anatomical specimens for educational purposes at the Department of Anatomy, Physiology, and Animal Science, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Forestry, Sofia, Bulgaria, were used for the morphometric measurements. All dogs were donated to our department by their owners after euthanasia for reasons unrelated to this research. Owners signed written consent for the cadavers to be used for scientific and publication purposes, according to the University of Forestry ethical principles. The samples were divided into three groups according to size, with 5 samples per group – large (over 20 kg), medium (10-20 kg), and small (less than 10 kg).

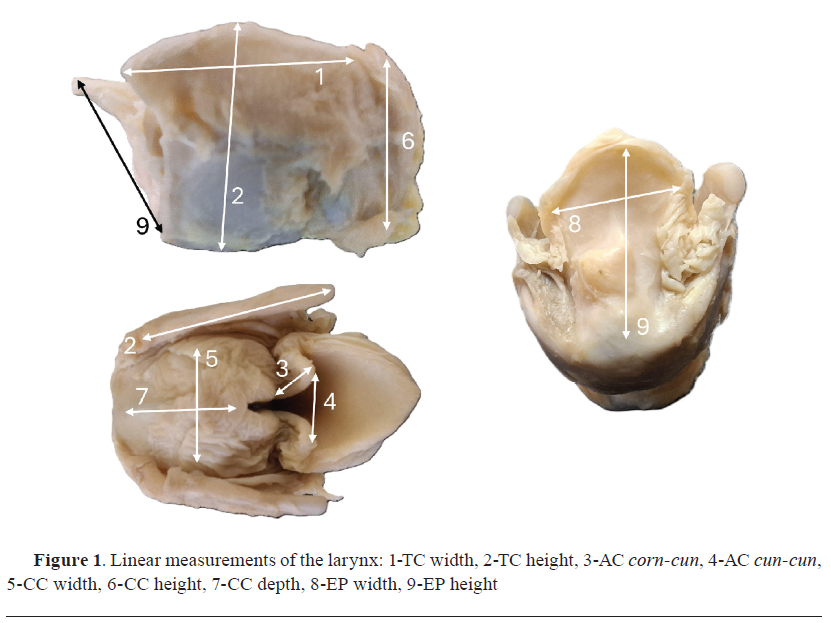

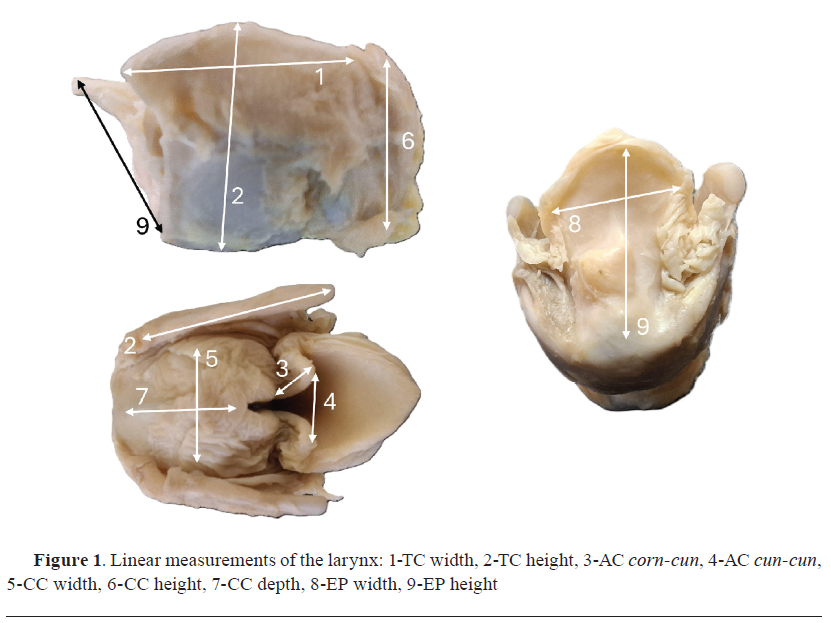

Methods MorphometryThe morphometric study was conducted as described by Bejdić et al. (

23). An instrument for precise measuring – 150 mm Stainless Steel Electronic Digital Vernier Caliper Micrometer (Jiavarry

®, United States) was used for linear measurements of the laryngeal cartilages. It was performed in the following order: thyroid cartilage (TC) width and height; arytenoid cartilage (AC) – distance between

processus corniculatus and

proc. cuneiformis (corn-cun), depth of ventricle and distance between the two

proc. cuneiformis (cun-cun); width, height, and depth of cricoid cartilage (CC); width and height of the epiglottis (EP)

(Fig. 1).

Acoustic analysis

Acoustic analysis

Live dog specimens (n=15; 5 per group) of similar size as the corresponding cadavers were used for sound recording in an outdoor environment, without human or other noise interferences. A professional digital recorder Zoom H1n (Zoom Corporation

®, Japan) was used. Recordings were made 1-3 m from the animals, in silent and wind-free conditions. The voice recordings were performed after obtaining written consent from the owners of the animals. Barks elicited in the context of agonistic behavior towards people who are strangers to the dogs were recorded. This method assured that the bark sound would be elicited by a homogenous factor since the acoustic characteristics may differ according to various behavioral and emotional inputs.

The acoustic parameters were obtained by Raven Pro 1.6 software (K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, US). The following acoustic parameters were obtained: Delta Time (s), Bandwidth 50% and 90% (Hz), Frequency 5%, 25%, 75%, 95% (Hz), Peak Frequency (Hz), Inband Power (dB), SNR (dB) and Power Density (dB/Hz). Spectrograms were created with 512-point Hann window 50% overlap time. Sound selections were manually verified.

Definitions of the acoustic parameters

Delta Time (s) is the duration of the sound – how long the sound lasts, measured in seconds (s).

Bandwidth 50% and 90% (Hz) measure how wide the sound is in frequency – that is, how much range of pitches the sound covers. They represent the range of frequencies that contains the middle 50% or 90% of the sound’s energy, measured in Hertz (Hz). Frequency 5%, 25%, 75%, and 95% (Hz) indicate which frequencies hold certain percentages of the total sound energy. F5% is the frequency below which 5% of the energy lies. It can be lower or higher than f0 depending on how energy is distributed in sound. F25% and F75% are like the “first and third quartiles” in a data set – the boundaries of the middle half of energy. F95% is the frequency below which 95% of the sound’s energy lies.

Peak Frequency (Hz) is the frequency where the sound is strongest (has the most energy). Like the “loudest pitch” or the “main note” in the sound.

Inband Power (dB) is the total loudness of the sound, within a specific frequency range.

SNR (dB) indicates the sound clearance compared to background noise. A higher SNR means a clearer, more distinct sound. A low SNR means the sound is hard to hear because of the noise.

Power Density (dB/Hz) is the amount of power (loudness) in each small slice of frequency. It’s measured in decibels per Hertz (Hz).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with SPSS 26 (IBM

®, United States). The acoustic parameters were compared with the Kruskal-Wallis test. The values were adjusted using the Bonfferoni correction. The same statistical test was applied for the linear measurements of the laryngeal cartilages in the three groups. We ranked the differences in the groups for each measurement with statistical significance by the Pairwise comparisons. The correlations between acoustic and morphometric parameters were analyzed with Spearman’s correlation test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

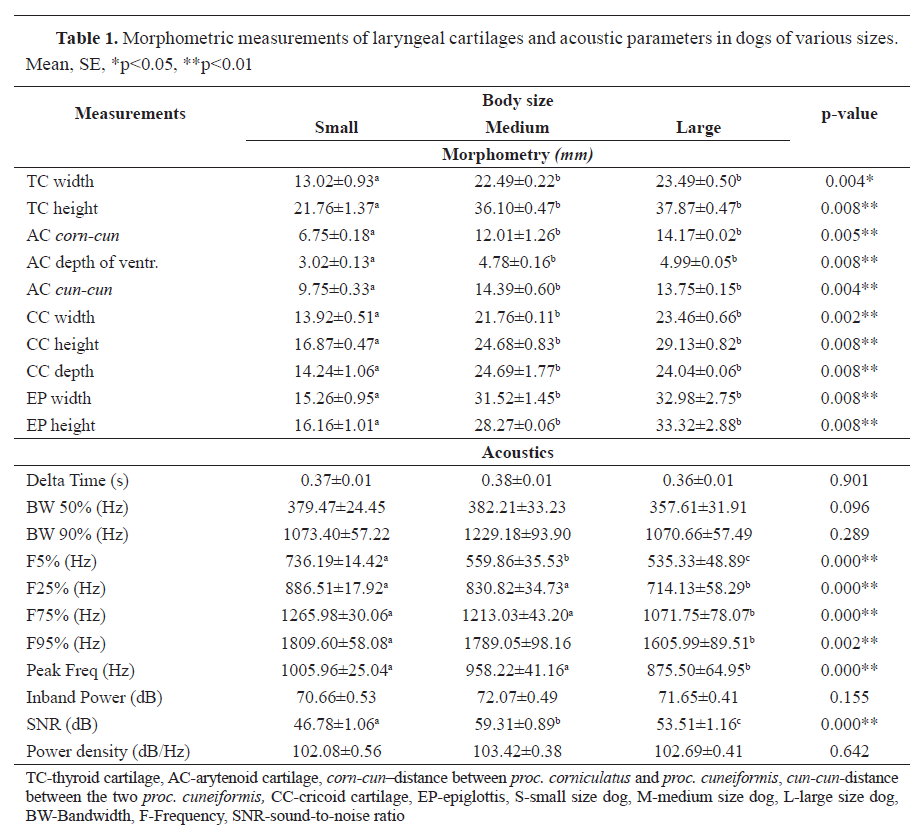

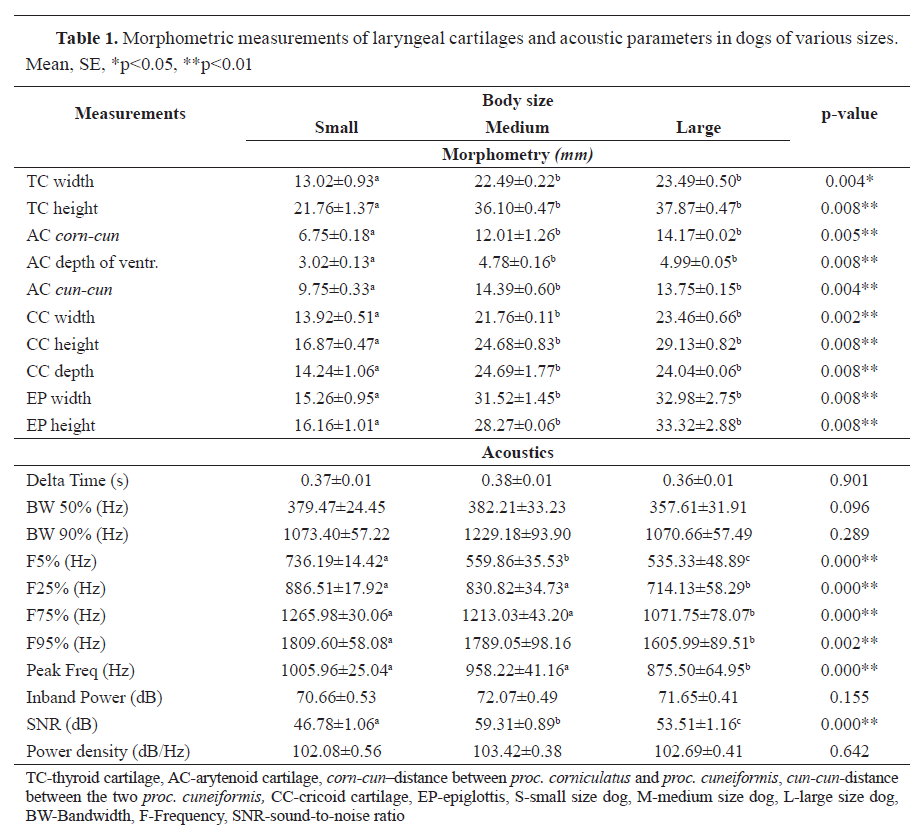

RESULTSThe pairwise comparison test revealed that small animals significantly differed from large in all measurements (

Table 1). They exhibited significantly higher F5%, F25%, and F95% values than large dogs (p<0.01). The acoustic parameters F5%, F25%, F75%, F95%, Peak Freq (Hz), and SNR (dB) were significantly different among the three groups (Table 1). Pairwise comparisons ranked the large dogs with lowest frequency sounds (535.33±48.89; p<0.0001), whereas medium-sized dogs with highest (highest SNR, 59.31±0.89; p<0.0001). the lowest values were obtained for the first (F25%), third (F75%) quartile, and F95%. In the large-size-dog group, peak frequencies were 714.13±58.29 (p<0.0001), 1071.75±78.07 (p<0.0001), 1605.99±89.51 (p<0.002), and 875.5±64.95 (p<0.0001), respectively.

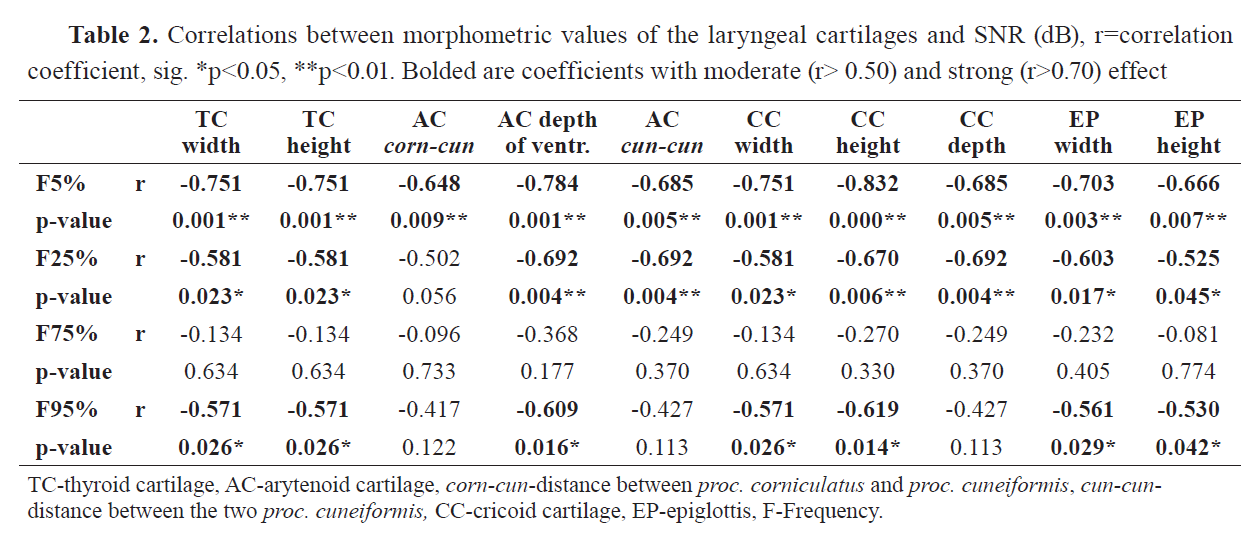

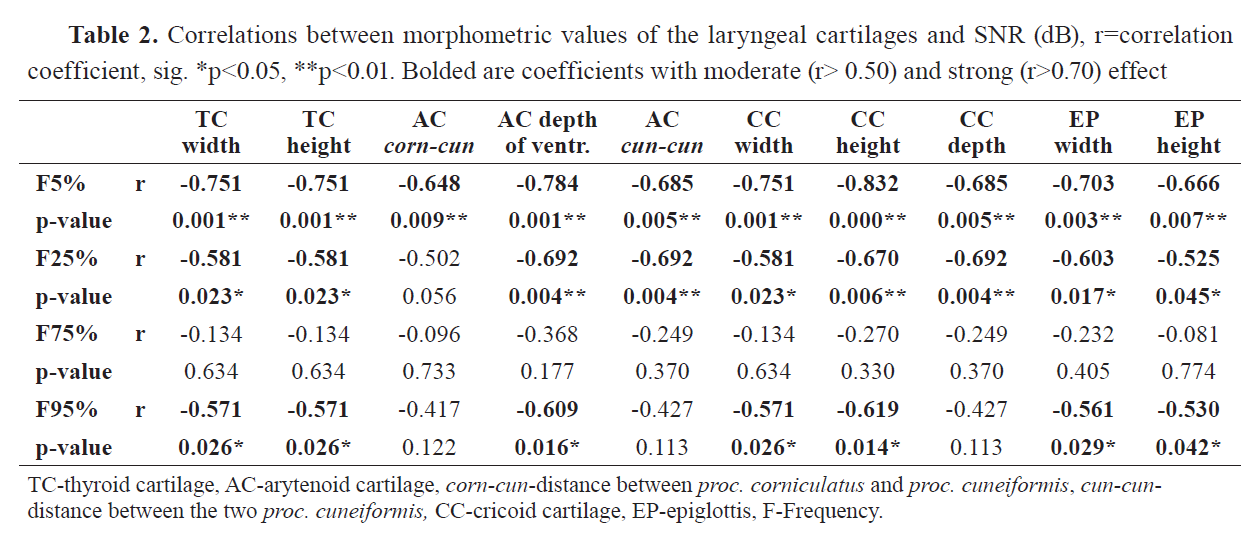

The Spearman correlation test showed a significant negative relationship between F5%, F25%, and F95% acoustic parameters and all linear metrics of the laryngeal cartilages (

Table 2). Most of the metrics explain over 50% of the variations in these three parameters, showing moderate correlation with them. There is also a strong co-dependency (r>0.70) in F5% and TC width and height, AC depth of ventricle, CC height and width, and EP width.

DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

The cricothyroid muscle stretches the vocal folds, increasing tension and stiffness, which leads to higher fundamental frequency (

28). The thyroid cartilage is the primary attachment point for the cricothyroid muscle and therefore, the height of this cartilage could indirectly influence the leverage and range of motion of the cricothyroid muscle. However, this claim needs objective evidence (

29,

30). The depth of the cricoid cartilage could influence the angle and effectiveness of the cricothyroid muscle’s pull since the cricoid cartilage forms the base upon which the thyroid and arytenoid cartilages sit.

The arytenoid cartilages are crucial for vocal fold adduction and abduction. While they do not directly affect the cricothyroid stretching action, their position and movement, which are dependent on their size, can influence vocal fold tension and, consequently, the perceived pitch (

31).

The epiglottis can contribute to vocal resonance, influencing the quality of the voice (

32). The position and shape of the epiglottis can modify the vocal tract, affecting the frequencies that are amplified (

27).

While the thyroid and cricoid cartilages provide the structural framework for the cricothyroid muscle to act upon, the arytenoids primarily influence vocal fold adduction.

According to the Pairwise comparison test for the linear morphometric measurements, there is a direct connection between the size of the cartilages in larynx and the body size. The current study demonstrated that Low (F5%), High Frequency (F95%) percentiles, as well as F25%, F75%, Peak Frequency, and SNR vary significantly depending on the size of the dog. Our results are consistent with the results of a study by Zhang (

18) that show differences in the size of the larynx in men, women, and children. Significant differences were observed in the frequency and amplitude of sound, with lower fundamental frequencies in adult males as compared to adult females and children. Hollien (

24) found that individuals with low-pitched voices have larger laryngeal tracts. A study from 2006 by Pfefferle and Fischer (

25), reveals that even though fundamental frequency can be volitionally modulated, it is of utmost dependence on the physical measurements. Dzierzęcka and Charuta (

26) confirm that larynx size and body weight in dogs are in correlation, and that TC height, and epiglottis width are parameters with the highest variability. The study by Bowling et al. (

11) clearly revealed a reciprocal relationship between the frequency of communication signals and body size. Although this negative dependence is more clearly determined in primates, it has also been confirmed in carnivorous animals. Despite that the dominant frequency (the one at which the largest signal amplitude is recorded) is most preferred in the analysis of communication signals, the fundamental frequency (the frequency at which the vocal folds vibrate) is a better feature and is related with the body size in mammals. In the vocal signals of carnivores, a disparity in structure is observed; atonal elements are much more common, compared to other mammals (

11). The greater variety of sounds in these animals is inevitably associated with more complex forms of behavior and social relationships with humans. This probably explains the weaker size-frequency dependence in the larynx of these animals.

Only F5%, F25%, and F95% showed significant negative correlations with the distinct morphometric values of the laryngeal cartilages, indicating their role in the sound formation. Furthermore, it was established that these acoustic variables cause strong to moderate effect on the sound characteristics in relation to the larynx proportions (

Table 2), while the rest of the acoustic parameters showed weak or no effect at all. F75% showed no such co-dependency and remained stable. However, this could be explained by the fact that barks in aggressive context have concentrated energy in the low to mid frequencies. Aggressive barks often show a skewed energy distribution, heavily weighted toward the lower frequencies, reflecting urgency (

5). F25% and F95% percentiles represent the lower and upper extremes of the frequency spectrum, respectively. Changes in laryngeal size or stiffness can shift energy distribution, potentially affecting these values. F75% as a mid-upper percentile and from our results it seems to be less sensitive to changes in laryngeal size and more influenced by other factors such as vocal tract configuration, not by laryngeal cartilages size alone. F25% and F75% parameters can have different patterns of variation, depending on the call structure, context, or species. They represent different points on the frequency distribution of a sound, based on energy or amplitude. Frequency 25% is the frequency below which 25% of the total energy occurs, and Frequency 75% is the frequency below which 75% of the total energy occurs. While they are both derived from the same sample from each examined animal, and are thus not completely independent, their specific values depend on the spectral shape. Ey et al. (

33) reviewed and discussed these acoustic correlates and how they relate differently to size and other traits. Rameau et al. (

35) findings suggest that alterations in the laryngeal environment can impact the distribution of acoustic energy across frequencies. This shows that frequency parameters like these may encode different individual traits. The usage of multiple frequency parameters may capture the shape and dynamics of calls, highlighting that lower and upper energy quartiles contribute unique information (

34). Although there aren’t any direct studies that confirm our results, and this is not the main aim of our primary research, we think that the distribution of energy in the sound is a key to decoding animal vocalizations. The significant negative correlation between frequency percentiles and cartilage dimensions supports the hypothesis that laryngeal morphology constrains the acoustic range of barking. Larger cartilages have lower vocal fold tension, resulting in lower frequency outputs.

Methodology limitations

Two different dog batches were used for the morphometric and acoustic analyses. The acoustic data were acquired from an already existing dataset. The data collection from a single batch of dogs would have violated the Ethics statement for animal protection and welfare because no diagnostic imaging devices were available for the purposes of the present research. Nevertheless, our research still presents novel and valuable comparative data and deeper insight into vocalization production mechanisms.

CONCLUSION

The current research showed that different frequency parameters (F5%, F25%, and F95%) co-vary in relation to changes in laryngeal cartilages size. They are in negative dependency with the size of these anatomical structures. In contrast, F75% did not show such tendency, proving that different frequency parameters can encode individual information and could aid in determining the dynamic structure of communication vocalizations. This approach allows researchers to quantify the shape and spread of the energy distribution, not just central tendency (like F50% or Peak Frequency). It is useful for differentiating between emotionally charged barks and identifying subtle vocal modulations. Such percentile measures provide finer resolution of individual acoustic profiles. Further research using F5%-95% parameters can help detect intensity with greater sensitivity involving histological findings in vocal cords. While some dog vocalization studies use F0, peak frequency or formants, relatively few examine full energy percentiles across the spectrum. Including multiple percentiles offers more robust statistical modeling, better signal comparison across contexts and a novel multi-dimensional acoustic fingerprint of vocalizations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial conflict of interest regarding authorship and publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was supported by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Forestry, Sofia, Bulgaria.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

PIH recorded and analyzed the acoustic parameters, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the draft manuscript. ISRG collected the cadaveric materials, conducted the morphometric study, contributed to the manuscript writing. MSC formed the experimental plan, contributed to the manuscript writing and performed critical revision.

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0032

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0032