Co-infection significantly influences disease severity. This study investigated the impact of co-infections with Escherichia coli (E. coli) O78 and Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG), alone and in combination, on the pathogenicity of low- pathogenic avian influenza H9N2 in specific pathogen-free (SPF) chickens. Seventy one-day-old SPF chicks were divided into seven equal groups (G), where G1 is the control one, G2-G4 were infected with H9, MG, and E. coli, respectively, and G5-G7 were co-infected with MG-H9, E. coli-H9, and MG-E. coli-H9, respectively. The study monitored clinical symptoms, mortality rates, H9N2 hemagglutination inhibition antibody titers, viral shedding through qRT-PCR, and histopathological changes in experimentally infected groups. The findings revealed that the group co-infected with all three pathogens had the highest significant mortality rate (70%), with severe clinical symptoms, moderate histopathological changes in the trachea and lungs, along with the highest significant hemagglutination inhibition antibody titers (6.40±0.52, 7.30±0.67 log2) at 7 and 14 days post-infection, respectively. This group also demonstrated the highest viral shedding (3.53±0.01, 4.53±0.09, 3.60±0.05 log10 EID50/ml) at 2, 4, and 7 days post-infection, respectively, with significant differences, and the longest duration of H9N2 shedding (10 days post-infection). In summary, co-infection enhanced the pathogenicity of H9N2; furthermore, co-infection with E. coli O78 increased H9N2 pathogenicity more than co-infection with M. gallisepticum, and the combination of both bacteria resulted in the highest pathogenicity of the H9N2 virus.

INTRODUCTION

The H9N2 subtype of avian influenza viruses (AIVs), a member of the Orthomyxoviridae family, has been isolated from poultry outbreaks in several countries over the past 15 years, including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt, China, Israel, South Africa, Germany, and Hong Kong (

1).

H9N2 was first isolated in Egypt in 2011; subsequently, it spread to all governorates and domestic birds throughout the country and was classified as an Israeli virus belonging to the Qa/HK/G1/97 lineage (

2,

3). Despite being considered relatively nonpathogenic in experimental settings, H9N2 viruses can cause mild respiratory symptoms, leading to significant morbidity and mortality; moreover, co-infection with bacteria and other viruses can further reduce egg production (

1).

Respiratory diseases in poultry are primarily caused by pathogens acting alone or in combination, resulting in substantial financial losses for the Egyptian poultry industry. Clinical symptoms associated with various respiratory viruses in poultry are similar and can be confusing (

4,

5). Pathogen virulence plays a significant role in disease severity; additionally, other factors such as age, species susceptibility, environmental conditions, management practices, and the concurrent secondary diseases may contribute to higher morbidity and mortality in chickens (

6).

Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG), a highly consequential pathogen, causes severe airsacculitis; specially when it coexists with other respiratory pathogens, such as LPAIVs. MG-H9N2 co-infection results in high mortality rates, ranging from 10% to 60% (

7).

E. coli is the primary pathogen causing colibacillosis, one of the most prevalent disease affecting chickens and associated with substantial economic losses.

E. coli co-infection enhances the virulence of several viral and bacterial diseases, including LPAIV H9N2 (

8).

This study assumes that co-infection with

M. gallisepticum and

E. coli together with AI H9N2 results in synergistic pathogenic effects that exacerbate respiratory disease severity, immunosuppression, and mortality in poultry compared to single or dual infections. Therefore, this experimental investigation aims for examining the pathogenic potential of a LPAIV H9N2 infection in the presence of either or both MG and

E. coli O78 based on of clinical signs, mortality, viral shedding, histopathological alterations, and viral seroconversion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Viral and bacterial strains

All strains used in this study were generously provided by the Reference Laboratory for Veterinary Quality Control on Poultry Production (RLQP), Giza, Egypt as follows: a recently circulating strain of AIV H9N2, A/chicken/DN/2023 (accession number PP857689), as well as bacterial strains of

M. gallisepticum and

E. coli O78 were used.

Specific pathogen free chicks and embryonated chicken eggs

Seventy one-day-old SPF chicks, were obtained from the SPF egg production facility in Kom Oshim, El-Fayoum, Egypt. These chicks were raised in HEPA-filtered isolators under optimal conditions for lighting, airflow, temperature, feed, and water at the Central Laboratory for Evaluation of Veterinary Biologics (CLEVB) in Abbasia, Cairo, Egypt. Additionally, ten-days-old SPF embryonated chicken eggs (ECEs) were sourced from the same farm for the propagation and titration of the H9N2 virus.

Experimental design

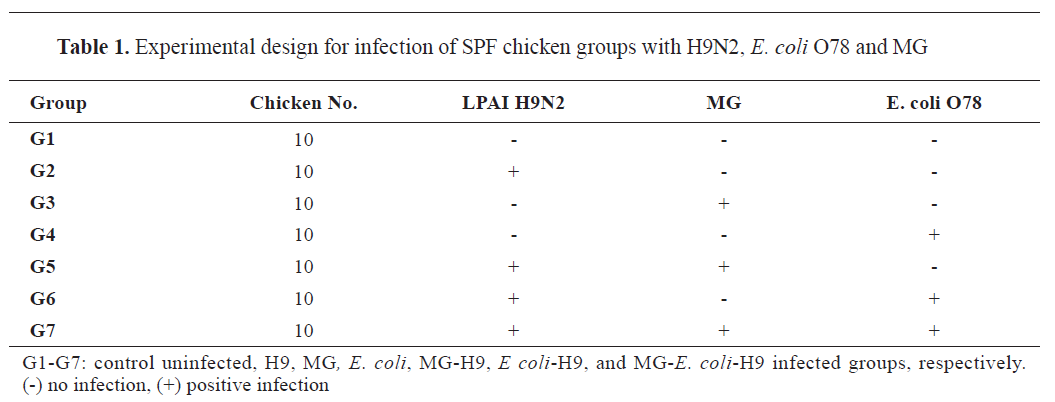

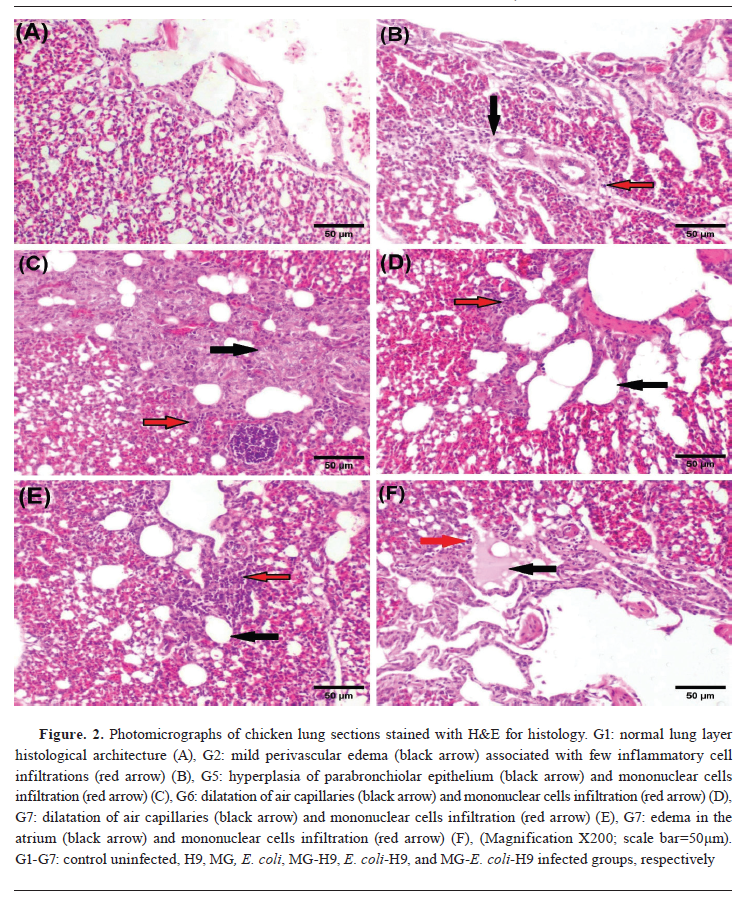

As shown in

Table 1, the chicks were divided into seven groups, with 10 chicks in each group. Group 1 (G1) served as an uninfected control, while group 2 (G2) (H9) received an intranasal (I/N) infection with H9N2 influenza virus (10

6 EID

50/0.1 ml) at 25 days of age. Group 3 (G3) (MG) was administered 0.2 ml of MG (10

9 CFU/ml) intratracheally (I/T) at 18 days of age. Group 4 (G4) (

E. coli) received 0.2 ml of

E. coli O78 (10

8 CFU/ml) I/T at 21 days of age. The last three groups received mixed infections using the same doses, routes, and timings as the positive control groups as follows: group 5 (G5) (MG-H9) was infected with MG and H9N2, group 6 (G6) (

E. coli-H9) received

E. coli and H9N2, and group 7 (G7) (MG-

E. coli-H9) was subjected to all three infections.

Clinical signs and mortality rates

Clinical signs and mortality rates

Daily monitoring was conducted for clinical signs and mortality rates in all groups after infection until the end of experiment (14 days post- H9N2 infection). Special emphasis was placed on the respiratory disorders, including nasal discharge, head swelling, tracheal rales, sneezing, difficulty breathing, and coughing.

Establishment of successful bacterial infection

Confirmation and identification of MG by PCR and

E. coli O78 using standard bacteriological procedures were performed before H9N2 infection and at the end of experiment. Tracheal swaps were collected for detection of

16S rRNA gene for Mycoplasma by PCR using specific primers (

9), while fecal swaps were obtained for

E. coli bacteriological isolation on peptone water then MacConkey Agar (

10).

Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) test

Blood samples were collected from all groups on the 7

th and 14

th day after H9N2 infection. Sera were separated and used by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) against the H9N2 virus following the guidelines for the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) (

11).

Viral shedding

Tracheal swabs (five samples per group) were collected on days 2, 4, 7, and 14 post-H9N2 infection for virus quantification using quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Viral RNA was extracted from the swabs using a Qiagen viral RNA micro kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was used to titrate viral RNA as described by Ben Shabat using H9 specific primers, a Qiagen one-stage kit (Qiagen, Germany), and a reference curve using a known titer of the H9 strain (

12).

Histopathological studies

On day 14 post-H9N2 infection, all birds were euthanized for histopathology. Tracheal and lung specimens were collected, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and sectioned at 5 µm thickness. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (

13). Light microscopic examination and histopathological lesion scoring for the trachea and lung in all groups were recorded according to the following scoring system: (−) absent, (+) mild, (++) moderate, and (+++) severe (

14).

Statistical analysis

All results were statistically evaluated using IBM Corporation’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28. ANOVA was used for group comparisons, and the Tukey post-hoc test was employed for multiple comparisons (

15).

Data were presented as mean ± standard error (SE). The Chi-square (χ2) test was used to compare categorical datawhen the expected frequency was less than 5, and statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 (

16).

Ethical approval

All experimental animals in this study were handled in strict accordance with and adherence to the relevant policies regarding animal care, as mandated by international, national, and/or institutional guidelines. This was approved by the Animal Research Ethical Committee for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals in Education and Scientific Research (SCU-VET-AREC), Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt, under code: SCU-VET-AREC 2025013.

RESULTSVirus

The LPAIV H9N2, A/chicken/Egy/DN/2023, yielded a titer of 10

8.5 EID

50 /ml.

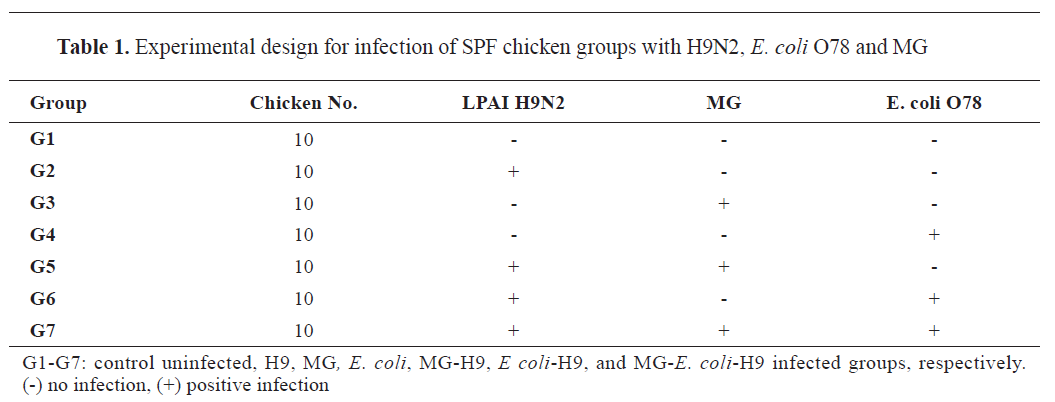

Clinical signs

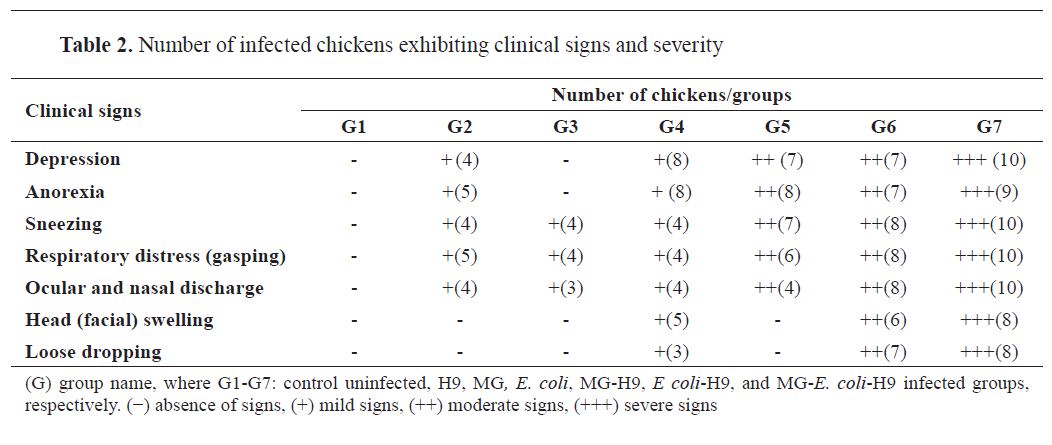

Neither clinical signs nor mortality were observed in the uninfected control chicken group (G1). 50% of chickens in group G2 exhibited mild depression and anorexia, followed by mild sneezing and gasping from 5 to 14 days post-infection (dpi) with H9N2 virus. Four chickens in group G3 showed sneezing and gasping after 6 days of MG infection; then, they had ocular and nasal discharges (

Table 2).

Most chickens in group G4 developed mild depression and anorexia at 3 days following

E. coli O78 infection, while only 3-5 chickens showed mild sneezing, gasping, ocular, and nasal discharges, mild facial swelling, and loose dropping (

Table 2).

Chickens in groups G5 and G6 exhibited moderate clinical signs from 2 dpi of H9N2 virus, including depression, anorexia, ocular and nasal discharges and respiratory distress, as sneezing and gasping, while signs became more obvious from 6

th dpi of H9N2 virus. In group G6, signs were accompanied by loose dropping and facial swelling (

Table 2).

In group G7, severe clinical signs in chickens appeared at 2 to 14 dpi of H9N2 virus, including depression and anorexia, followed by severe respiratory distress, ocular and nasal discharges, and facial swelling (

Table 2).

Mortality

Neither the G1 negative control group nor G2 H9 control group were recorded with mortality. Mortality rates in groups G3 and G4, which were infected with either MG or

E. coli O78, respectively, were 10% and 20%, respectively.

The total mortality rate increased in groups G5 and G6, which were co-infected with either MG or

E. coli O78 along with H9N2 virus, respectively, to reach 40-50%, respectively, with significant differences from groups G1, G2, G3, and G4. This rate became higher in the group co-infected by both MG and

E. coli O78 along with H9N2 virus (G7) to reach 70% with significant differences from groups G1, G2, G3, and G4.

Successful establishment of bacterial infection

MG and

E. coli O78 tested positive before H9N2 infection and at the end of the experiment by PCR and isolation, respectively.

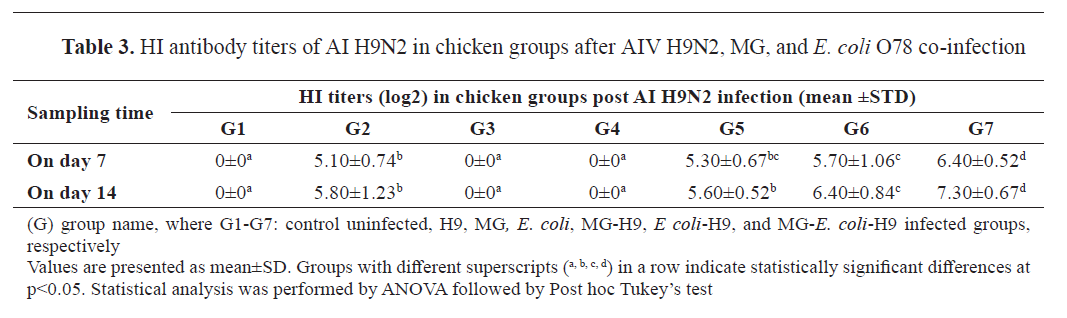

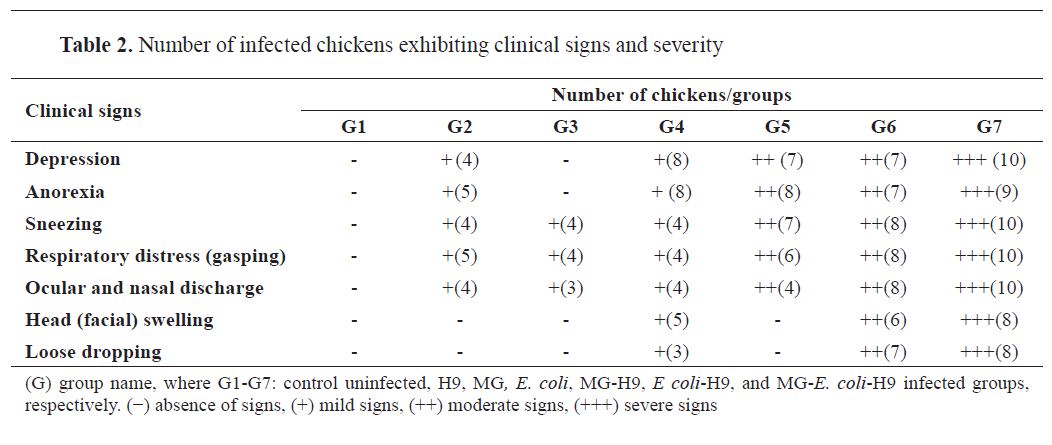

Hemagglutination inhibition

The HI test was used to detect anti-H9N2 antibodies in sera collected at 7 and 14 dpi with H9N2. Birds in the group infected with H9N2 alone (G2) had HI titers (5.10±0.74 and 5.80±1.23 log2), respectively, whereas sera from the negative control (G1), MG (G3), and

E. coli O78 (G4) groups were negative (

Table 3).

The G2 results were lower than those of the group co-infected with

E. coli and H9N2 (G6) (5.70±1.06, 6.40±0.84 log2), but they were almost identical to those of the group co-infected with MG and H9N2 (G5) (5.30±0.67, 5.60±0.52 log2), respectively. However, HI titers were considerably higher in the G7 group, which was co-infected with

E. coli, MG, and H9N2 (6.40±0.52, 7.30±0.67 log2), respectively (

Table 3).

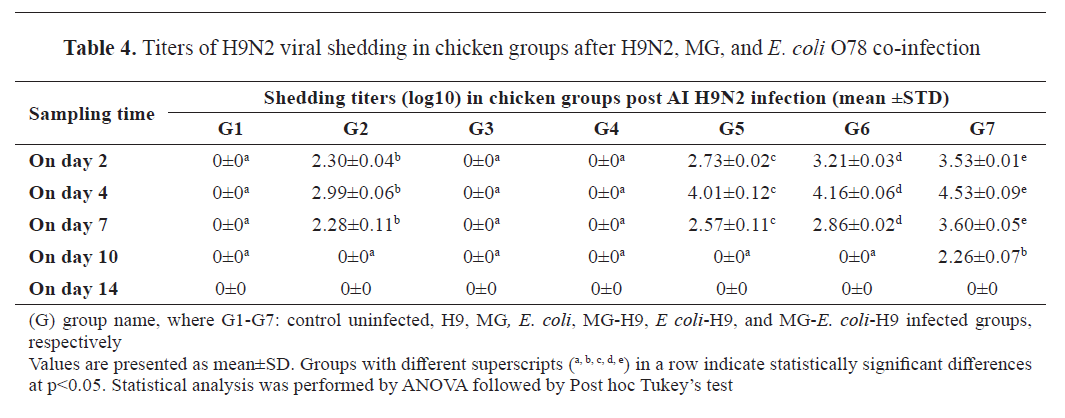

Virus shedding

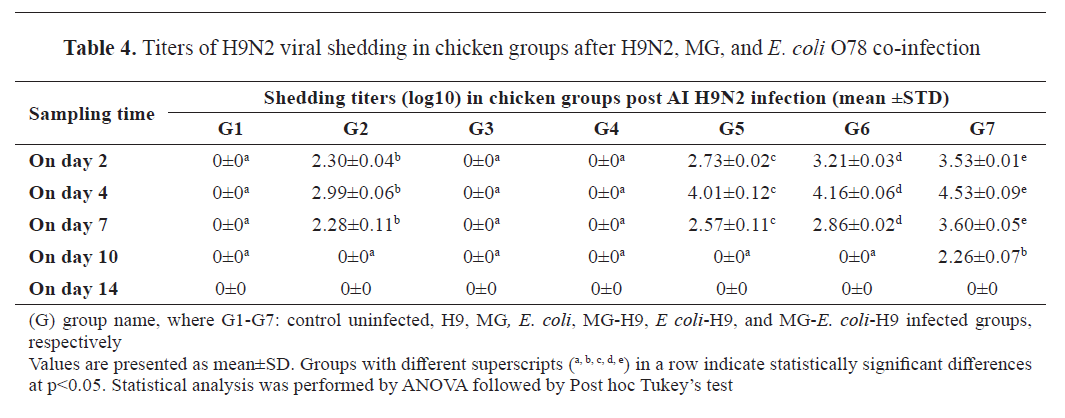

Virus shedding

All swab samples from groups G1, G3, and G4 were negative for H9N2. Group G5 had higher viral shedding titers (2.73±0.02, 4.01±0.12, 2.57±0.11 log10 EID

50/ml, respectively) than G2 (2.30±0.04, 2.99±0.06, 2.28±0.10 log10 EID

50/ml, respectively) on 2, 4, and 7 dpi of H9N2 virus, respectively, with significant differences (p<0.001 for each) (

Table 4).

Group G6 developed higher viral shedding titers (3.21±0.03, 4.16±0.06, 2.86±0.02 log10 EID

50/ml, respectively) than G2 and G5 on 2, 4, and 7 dpi of H9N2 virus, respectively, with significant differences (p<0.001 for each). As well, viral shedding for groups G2, G5, and G6 stopped at 7 dpi (

Table 4).

Group G7 showed the highest viral titers (3.53±0.01, 4.53±0.09, 3.60±0.05 log10 EID

50/ml, respectively), with significant differences (p<0.001). Shedding in group G7 extended to 10 dpi with a titer (2.26±0.07 log10 EID

50/ml) (

Table. 4).

Histopathological studies

Light microscopic examination of tracheal tissue in the experimental groups demonstrated a normal histological architecture of tracheal layers in group G1 (

Fig. 1A); while, tracheas from group G2 exhibited apparently normal tracheal tissue with sparse mononuclear cells in the lamina propria (

Fig. 1B).

Tracheal tissues of groups G3 and G4 showed a little amount of edema and congestion (data not shown); whereas, tracheas of groups G5 and G6 displayed a mild amount of edema in lamina propria with a small number of mononuclear cell infiltrations (

Fig. 1C and

D).

On the other hand, tracheal tissue of chickens from group G7 appeared to have hyperplasia of mucous-secreting glands, and moderate edema in lamina propria associated with mononuclear cell infiltrations (

Fig. 1E and

F).

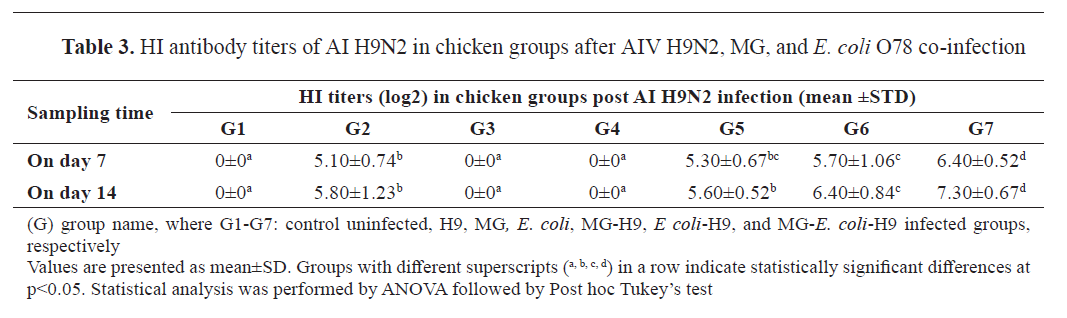

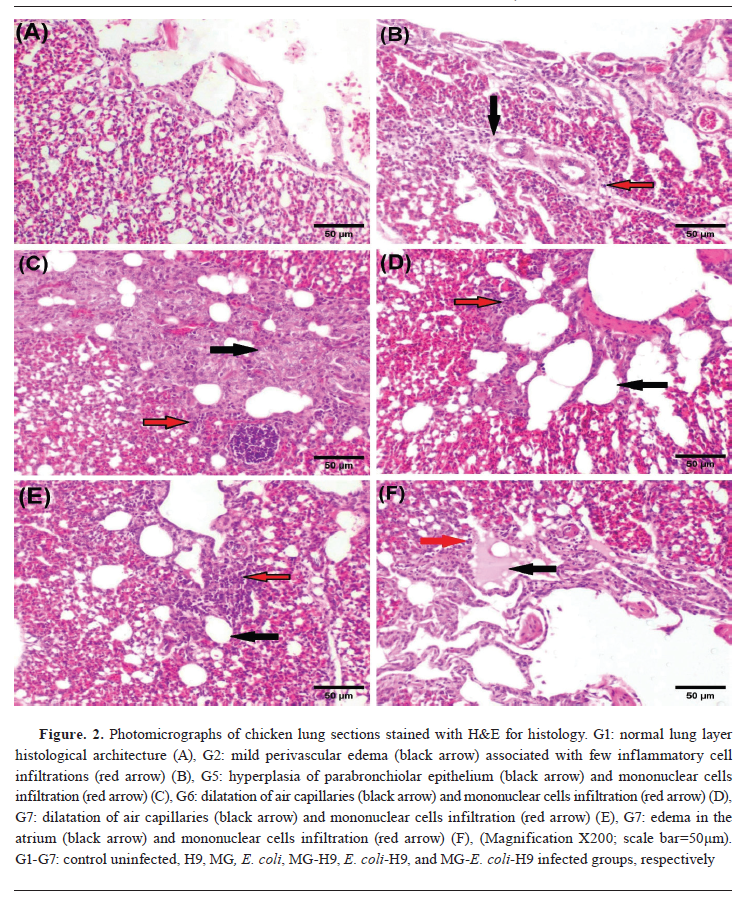

Concerning lungs, chickens from group G1 showed a normal histological architecture (

Fig. 2A).

Meanwhile, lungs of chickens from group G2 only exhibited mild perivascular edema (

Fig. 2B). Furthermore, groups G3 and G4 showed mild congestion and edema (data not shown).

Lungs of chickens from group G5 showed mild congestion of blood capillaries, edema, hyperplasia of para-bronchiolar epithelium and mononuclear cell infiltrations (

Fig. 2C). Meanwhile, group G6 revealed mild congestion, oedema, dilatation of air capillaries and mononuclear cells infiltration (

Fig. 2D).

On the other hand, lunges of chickens from group G7 demonstrated moderate congestion, hyperplasia, dilatation of air capillaries, mononuclear cell infiltrations as well as edema in the atrium (

Fig. 2E and

F).

The severity of histopathological changes was determined by summarizing and scoring the changes as shown in

Table 5. Notably, mild changes were observed in groups G5 and G6 groups in comparison to group G2, while highest severity was detected in group G7.

DISCUSSION

DISCUSSIONLPAIV H9N2 was first identified in the USA in 1966 from turkey; then, it has become widespread in Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Africa (

17). It commonly affects various species, including chickens, quails, ducks, geese, and turkeys, and also has the potential to infect humans (

18). In Egypt, the H9N2 G1 lineage was initially detected in commercial bobwhite quails that showed neither clinical signs nor mortalities in November 2011. In field settings, H9N2 is endemic in poultry industry, leading to economic losses specially in the presence of secondary respiratory pathogens (

2). This study aimed for investigating the impact of bacterial co-infections with MG and

E. coli on the pathogenicity of a local H9N2 isolate in chickens, assessing clinical signs, mortality, viral shedding, seroconversion to H9 virus, and histopathological changes.

The results showed that the H9 control group had mild respiratory signs in 50% of chickens, with no mortality. Clinical signs and mortality increased in co-infected groups to be higher in

E. coli-H9 group and the highest in MG-

E. coli-H9 group; mortality rate reached 70% in the latter group (

Table 2). Clinical signs and mortality rates align with the WOAH report, which stated that LPAIVs typically cause mild or no clinical disease but can lead to more severe illness if exacerbating infections or adverse environmental factors are present; sometimes resembling highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) (

11). Pathogenic

E. coli co-infection with H9N2 virus exacerbates the pathogenicity of each other, as the immunosuppressive effect of

E. coli reduces the immune response to H9N2 virus, leading to increased viral replication and severity (

1); this explains the more severe clinical manifestations of

E. coli co-infection compared to MG.

HI is used as a gold standard test for H9N2 (

19); where HI titers of 4 log2 and higher are considered positive according to WOAH. Moreover, real-time RT-PCR was the method of choice for detection and quantification of viral shedding (

11). The results showed harmonious HI and viral shedding outcomes; that the both MG-H9 and

E. coli-H9 groups resulted in higher HI and viral shedding titers than the H9 control group, with significant differences. Additionally, the

E. coli-H9 group exhibited higher results than MG-H9 group, with significant differences. Among the groups, the MG-

E. coli-H9 group had the highest HI titers, viral shedding titers, with significant differences, and it had also the most prolonged viral shedding period (10 dpi) indicating an increased viral replication and pathogenicity due to co-infection. The HI seroconversion and viral shedding results are in agreement with previous studies that emphasize the pathologic synergism between viral and bacterial co-infections (

8,

20,

21).

MG is often associated with other pathogens due to its ability to down-regulate host immune responses andevade the host immunity. Additionally, MG usually activates an inflammatory response and it inhibits the p53-mediated response, which normally triggers the cell cycle and apoptosis (

22,

23).

E. coli can spread quickly and produce peritonitis, severe airsacculitis, and bacteremia.

E. coli also triggers the production of harmful chemicals like nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide in host cells (

1). The MG-

E. coli-H9 group developed the highest disease severity due to synergistic effect of both pathogens on the pathogenesis of the virus. MG-

E. coli co-infection significantly increases expression of IL-17C, CIKS, NFκB, TRAF6, C/EBPβ, and inflammatory chemokines (

23). The current study showed

E. coli O78 co-infection influences H9N2 pathogenicity more than MG co-infection as

E. coli promotes the release of protease enzymes which help in HA antigen cleavability into HA1 and HA2 subunits, a key factor in tissue tropism, transmission of infection and toxicity of LPAIV (

1).

Histopathological investigation of MG-

E. coli-H9 group indicated a higher severity in the congestion, edema, mononuclear cell infiltration of both trachea and lung, as well as hyperplasia of parabronchiolar epithelium with dilatation of air capillaries in the lung. These histopathological findings were supported by WU outcomes, which indicated more severe inflammatory injury in case of MG and

E. coli co-infections than individual infections causing bronchial cilia loss and mucus accumulation in lungs of chickens. Wu stressed that viral infection typically reduces the antibacterial immune function in respiratory epithelium (

23). The histopathological results are consistent with previous studies, which observed more sever clinical symptoms and pathological lesions in case of co-infected groups with H9N2 and either MG or

E. coli than single infections (

21,

24,

25).

Despite providing valuable insights into the effects of co-infection by

M. gallisepticum and

E. coli O78 on the pathogenicity of avian influenza (H9N2) in SPF chicks, this study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results, as follows:

1.

Experimental Conditions vs. Field Settings: The co-infection model was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, which may not fully reflect the complexity and variability of field environments. Factors such as environmental stressors, vaccination history, and flock management practices could influence disease dynamics differently under real-world scenarios.

2. Strain Variability: The study utilized specific strains of AI H9N2,

E. coli, and

M. gallisepticum. However, genetic and pathogenic variability among field isolates may lead to different clinical outcomes. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all circulating strains.

Future studies should consider incorporating a broader range of field isolates, evaluating immune responses, and validating the findings under field conditions to enhance the applicability of the results to commercial poultry production.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that the H9N2 viral pathogenicity increases with either MG or

E. coli O78 co-infection; furthermore,

E. coli co-infection causes higher pathogenicity than MG co-infection; additionally, the MG-

E. coli-H9N2 co-infection leads to the highest pathogenicity by inducing the highest mortality rates, HI titer, viral shedding, and histopathological changes. The study stresses the necessity to employ new strategies to control co- infections in poultry production as the threat of co- infection grows with the intensive poultry industry.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared that they have no financial or non-financial conflict of interest regarding authorship and publication of this article.ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful and thankful to the ARC, CLEVB, RLQP and AHRI for their appreciated cooperation and support.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

NY developed the conception and design of the work. DMO conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. NMM and KAA performed the experiments and data analysis. DS, AS and FA followed up the practical work and data analysis. NAM was involved in work drafting and critically reviewed the manuscript. MAAAR followed up the practical work and data analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript for publication.

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0033

10.2478/macvetrev-2025-0033