Even though viral replication and typical clinical symptoms of the infection in pigs are exclusively limited to the upper and lower respiratory tract, there have been case reports demonstrating correlation of IAV with reproductive health issues in sows, probably related to the effect of cytokines. The trial was conducted in a subclinically infected high-performing 8,000-head sow herd immunised against the influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus using RESPIPORC FLUpan H1N1 (Ceva Santé Animale, Libourne, France). The aim of this longitudinal field investigation was to evaluate the alterations in key reproductive performance indicators (i.e. abortion rate, return to oestrus rate, farrowing rate, and number of piglets born alive, stillbirths, and born weak per litter) before and after implementation of the vaccine. A significant improvement in selected indicators was achieved. After implementation of the vaccination against the influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus, the mean abortion rate decreased significantly (p=0.0025) in site A, whereas it remained unaffected in Site B. The return to oestrus rate increased significantly (p=0.0091) in Site B only (2.23% to 2.97%). The mean number of piglets born alive increased significantly at both locations (p<0.0001), reaching 17.7 animals per litter in each. The mean number of weak piglets born per litter was not significantly affected. Analysis of the number of mummified and stillborn piglets revealed a significant reduction of these parameters at both locations. The mean farrowing rates were not significantly altered by the vaccination. The findings highlight the role of less obvious problems affecting porcine reproduction.

INTRODUCTIONInfluenza A virus (IAV), one of the six genera belonging to the family

Orthomyxoviridae, represents a significant global health threat to humans and some animals, including pigs (

1,

2). Characterized by its genetic reassortment and numerous subtypes defined according to hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) antigens, IAV provides a classical example of viral evolution leading to the emergence of novel viral subtypes. In 2009, the influenza (H1N1)pdm09 virus arose as a reassortment of Eurasian avian-like swine H1N1 influenza virus with a triple reassortant swine virus (human H3N2, North American avian, and classical swine H1N1 influenza virus) (

3). Concurrently to its rapid human-to-human transmission resulting in the World Health Organization pandemic phase 6 (

4), the virus infected swine farms worldwide

via humans (

5,

6).

The IAV infection in swine usually spreads by contact with oronasal secretions of affected individuals and results in a highly contagious respiratory disease with a varying spectrum of severity (

7,

8). Clinical manifestation of the disease is determined by virulence of the isolate, its antigenic subtype, the occurrence of secondary infections, age, immune status of pigs, and largely understood environmental conditions (

9). Even though viral replication and typical clinical symptoms of the infection in pigs are exclusively limited to the upper and lower respiratory tract (

10), there have been case reports demonstrating correlation of IAV with reproductive health issues in sows, probably related to the effect of cytokines (

11,

12). Nevertheless, the manifestation of IAV-related reproductive issues has not yet been successfully reproduced under an experimental framework (

13,

14).

There is no specific treatment of influenza in swine; however, antipyretics and antibiotics combating secondary respiratory bacterial infections are widely applied. Even though commercially available inactivated whole virus vaccines are primarily used as the element of sow vaccination programs providing piglets with protective maternally derived antibodies, empirical data obtained from linear field observations have demonstrated positive effects of the prophylaxis on broadly understood reproductive performance (

15). Therefore, the aim of this longitudinal field investigation was to evaluate the alterations in key reproductive performance indicators (i.e. abortion rate, return to oestrus rate, farrowing rate, and number of piglets born alive, stillbirths, and born weak per litter) in a subclinically infected high- performing 8,000-head sow herd before and after implementation of the vaccine against the influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus.

MATERIAL AND METHODSStudy farm characteristics

The study was carried out in a high-performing 8,000-head sow herd (Danish Genetics) located in Poland. As a consequence of its population size, the farm was divided into two systems (twin sites: A and B, 4,000 sows in each under the same management) weaning piglets in weekly batches. All the animals were reared on a slatted floor under conditions meeting the standards of Council Directive 2008/120/EC of 18 December 2008 laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. The farm followed strict biosecurity rules including fencing, inlets with protective mesh, dedicated staff, shower in/shower out, purchase of feed and semen from the same source, own transportation services, and security cameras. The herd was porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV)-negative,

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae-positive,

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae-negative, toxigenic

Pasteurella multocida-negative, and

Brachyspira hyodysenteriae-negative. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as the analyzed material was taken from a routine diagnostic procedure ordered by the farm owners. The authors had consent by the farm management that the data obtained from the diagnostic procedures could be used in scientific purposes.

Clinical and diagnostic information

Neither clinical presentation typical of the swine flu outbreak nor deterioration of production parameters was observed at the farm. The aim of sampling was to evaluate the need for a vaccination schedule update. Nasal swabs (using a sterile aluminum shaft and cotton tip) were collected by a veterinarian from 120 suckling piglets (60 from each side) following a cross-sectional profile (15 individuals from a group representing animals at 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks of age). The samples were placed in the individual tubes containing a viral transportation medium (350C Copan Universal Transport Medium System; COPAN Diagnostics Inc., Murrieta, CA, USA). For the aims of the investigation, the samples were pooled by 3, in respect of the age group and real-time RT-PCR testing. Positive samples with a Ct value <30 were subjected to further HA and NA subtyping (multiplex PCR) (

16).

Prophylaxis program

All sows reared at the locations were routinely vaccinated against leptospirosis and parvoviral infections and erysipelas using Biosuis Parvo L (6) (Bioveta a.s., Ivanovice na Hané, the Czech Republic) and ERYSENG (Laboratorios Hipra S.A., Amer, Spain) at every cycle, three weeks prior to artificial insemination. Influenza prophylaxis (Respiporc FLU3; Ceva Santé Animale, Libourne, France) was administered quarterly as a mass vaccination. Replacement gilts were multiplied internally at the farm and vaccinated against mycoplasmal pneumonia and porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) associated diseases using Mhyosphere PCV ID (Laboratorios Hipra S.A., Amer, Spain) administered post weaning, followed by Respisure 1 ONE (Elanco GmbH, Cuxhaven, Germany), and Ingelvac CircoFLEX (Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, Ingelheim/Rhein, Germany) administered prior to the estrus synchronization. Vaccines against the lesions caused by

Lawsonia intracellularis infection (Enterisol Ileitis; Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany), erysipelas (ERYSENG), Glässer disease (HIPRASUIS-GLÄSSER; Laboratorios Hipra S.A., Amer, Spain), influenza (Respiporc FLU3), leptospirosis, and parvoviral infections (Biosuis Parvo L(6)) were administered following the manufacturers’ recommendations. Vaccination schedules for all the above-listed products remained unchanged during the entire period of the investigation.

Vaccination against the influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus

Based on the results described above all the sows and replacement gilts at the study farm were primarily vaccinated with RESPIPORC FLUpan H1N1 (Ceva Santé Animale, Libourne, France). The second and subsequent mass vaccinations (using RESPIPORC FLUpan H1N1 and Respiporc FLU3 simultaneously) were completed two weeks later, and then in regular quarterly intervals. The vaccination schedule for maiden gilts was updated with RESPIPORC FLUpan H1N1 administered following the same timing as Respiporc FLU3.

Key reproductive performance indicators

The data regarding key reproductive performance indicators were obtained from a commercial management system used at the study farm (Cloudfarms; Cloudfarms AS, Bratislava, Slovakia). The abortion rate was calculated as the proportion (%) of the number of pregnancy terminations taking place in a period to the average sow number at the location. The return to oestrus rate was expressed as the ratio (%) of the number of repeated servings to all the servings within a period. The farrowing rate represented the proportion (%) of a number of sows farrowed to all sows served in a defined timeframe.

Experimental design

The data records from 17 consecutive weeks (March 2023-July 2023) after completion of the initial immunization against the influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus were defined as a transition period and intentionally excluded from the study because the vaccination was performed on already inseminated or pregnant sows. The data obtained for 35 consecutive weeks following the end of transition period (July 2023-March 2024) were subjected to a statistical analysis as these representing influenza A (H1N1)pdm09-vaccinated (Vac) dams (total 6005 and 6216 farrowings at site A and B). Records derived from a period of 35 weeks between July 2022 and March 2023 constituted for non-vaccinated (Non-vac) groups of animals (6130 and 6232 farrowings).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Reproductive parameters (abortion rate, return to estrus rate, number of piglets born alive/litter, number of weak born/litter, number of mummified piglets/litter, number of stillborn piglets/litter as well as farrowing rate) in site A and B were compared using Mann-Whitney test. Statistically significant level was set at

p-value < 0.05.

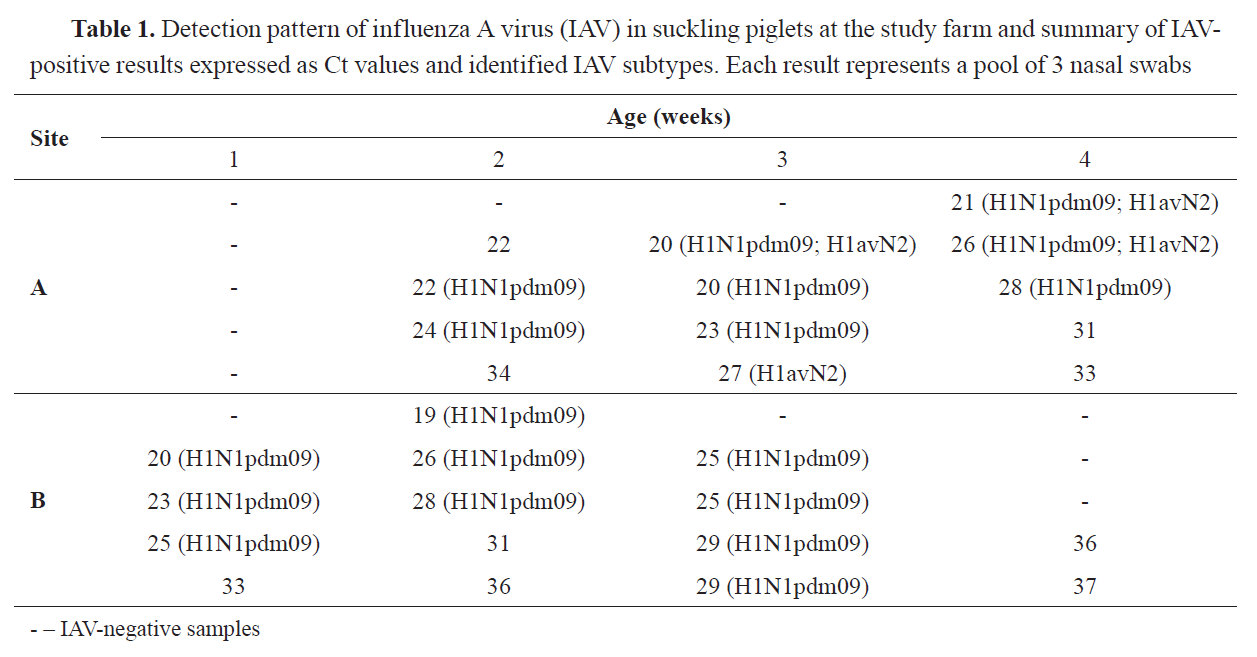

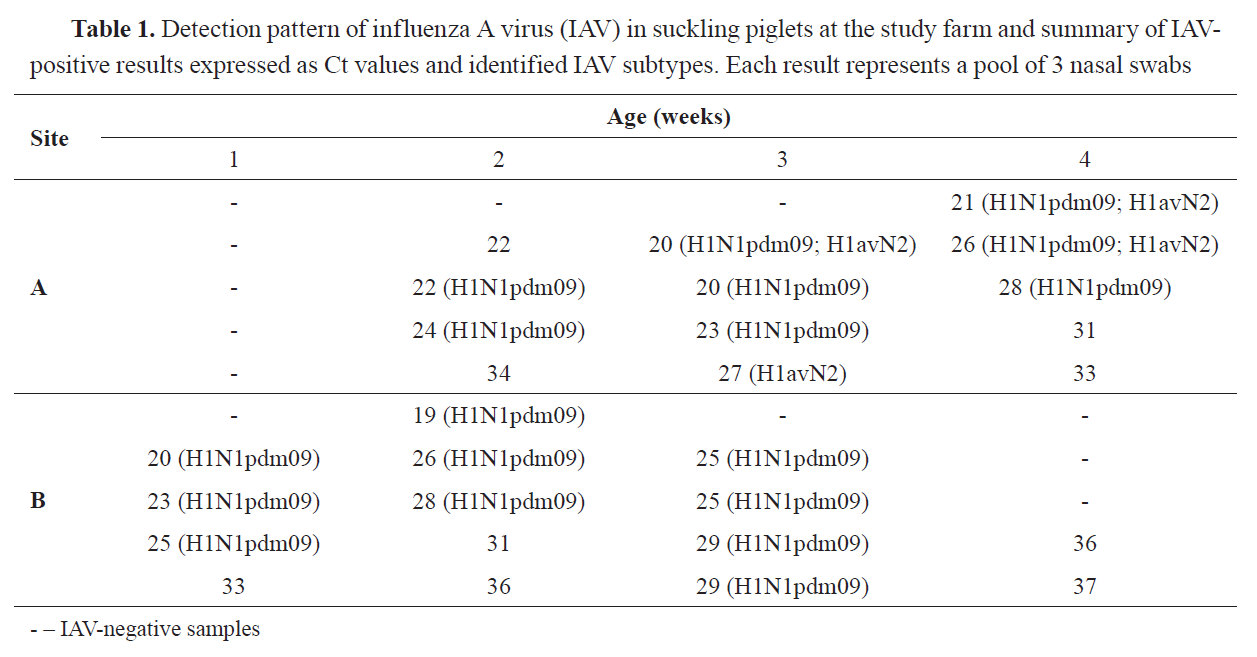

RESULTS70.0% (28/40) of all the tested pools were IAV-positive. 32.1% (9/28) of positive samples were not suitable for further subtyping (

Table 1).

The analysis of samples suitable for subtyping revealed presence of the influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 and H1avN2 viruses in 64.3% (18/28) and 14.3% (4/28) of the pools, respectively. Simultaneous detection of genetic material representing these viruses was not frequent and found in 10.7% (3/28) of the samples, obtained from groups of 3- and 4-week-old piglets reared in Site A only.

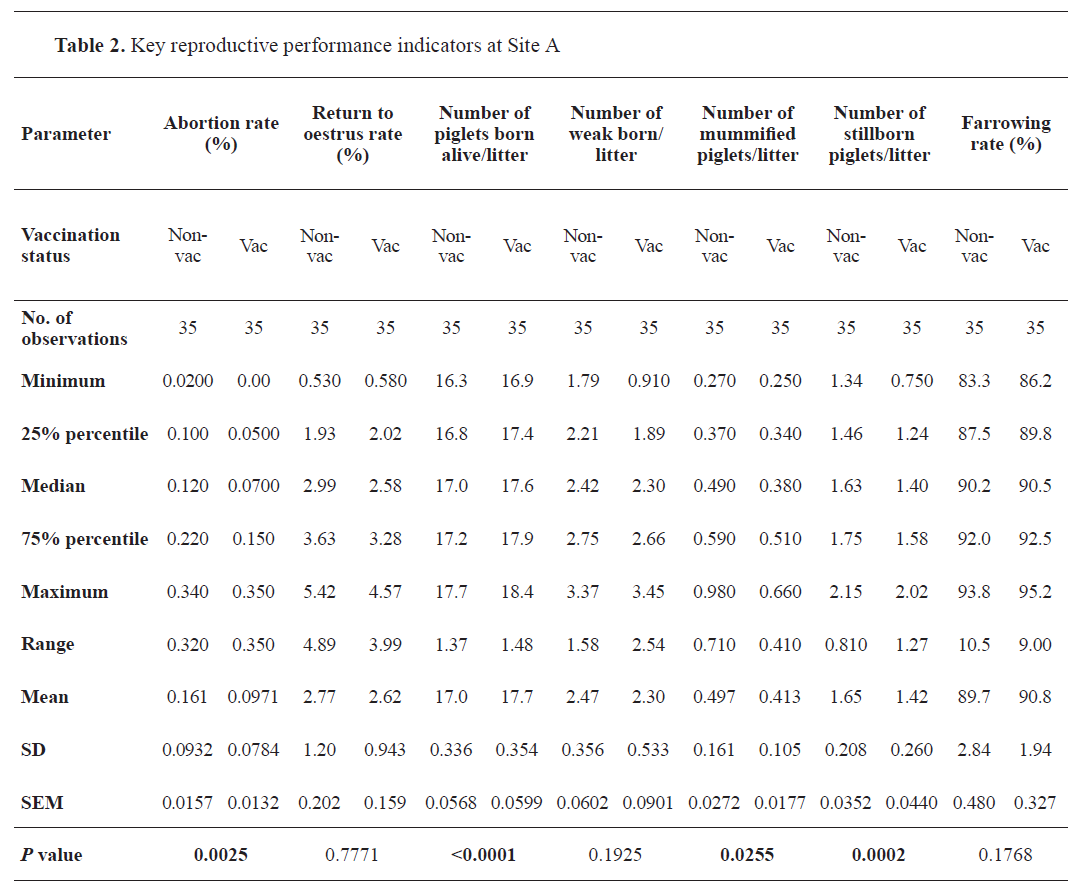

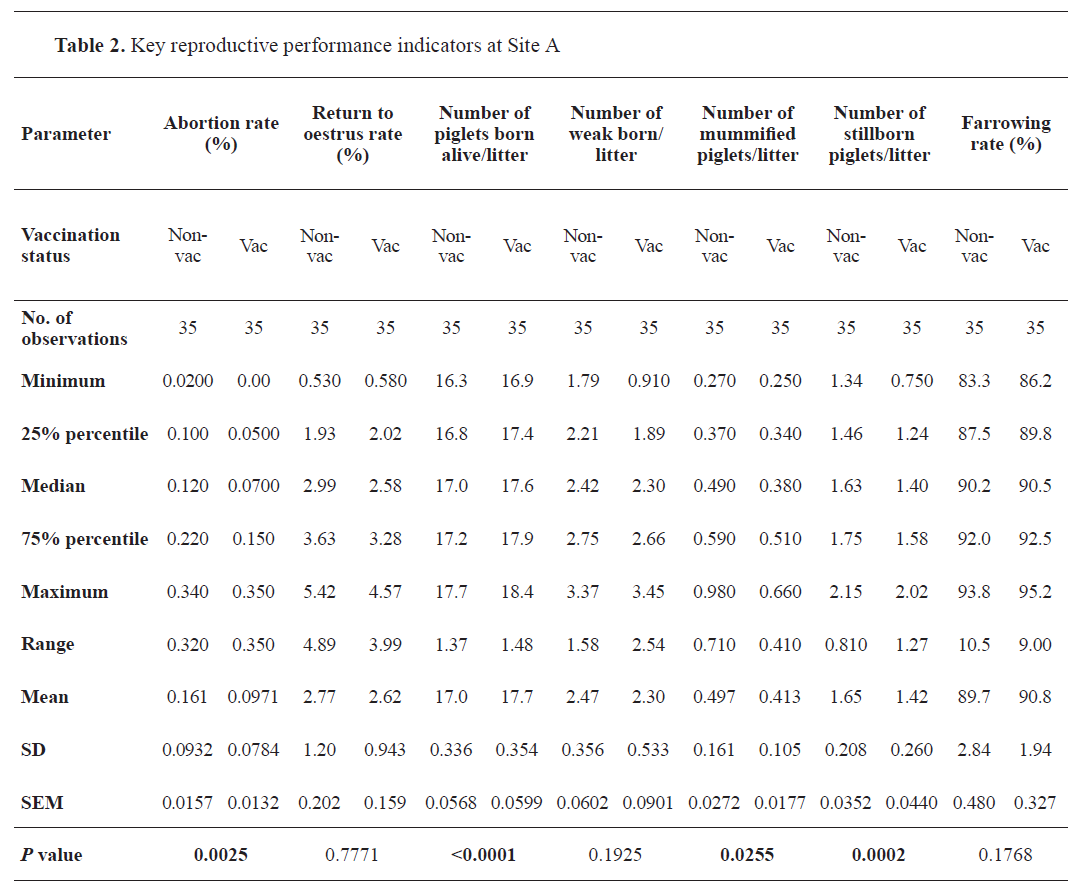

After implementation of the vaccination against the influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus the mean abortion rate decreased significantly (

p=0.0025) from 0.161% to 0.097% in Site A (

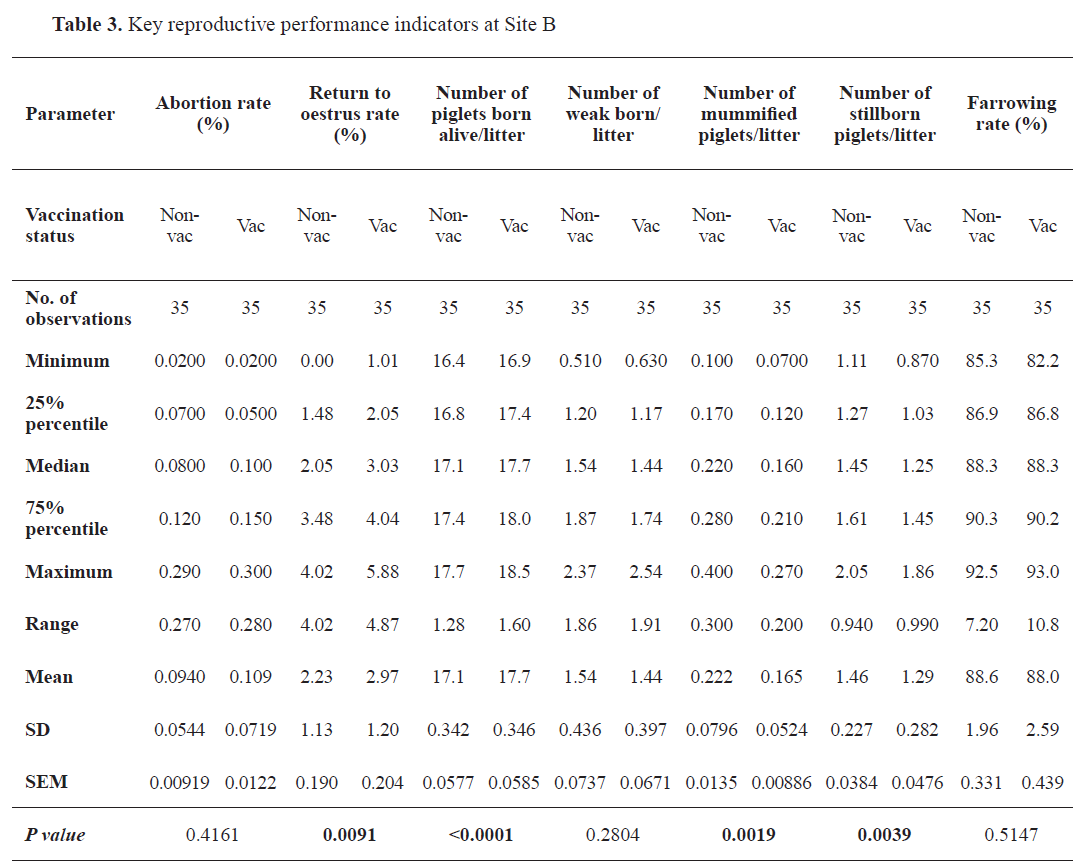

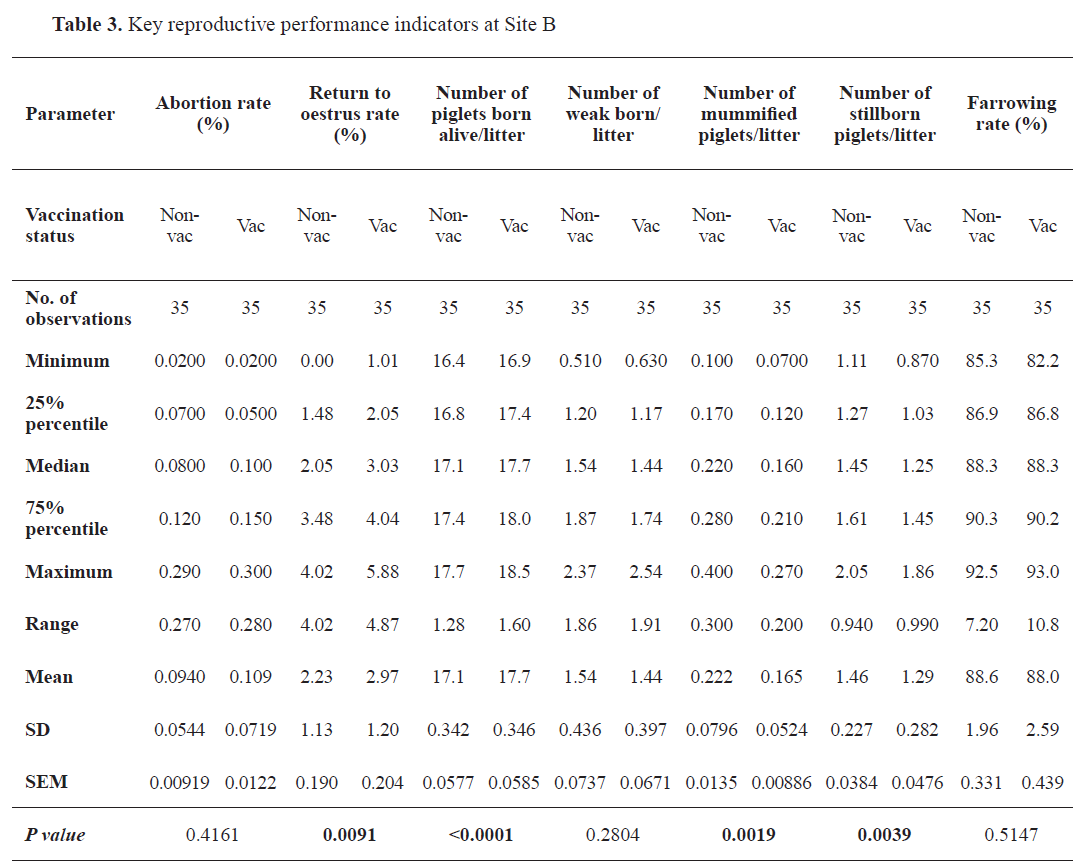

Table 2), whereas the parameter remained unaffected in Site B (

Table 3). Following the immunization, the return to estrus rate increased significantly (

p=0.0091) in Site B only (from 2.23% to 2.97%). Concurrently, the mean number of piglets born alive increased significantly at both locations (

p<0.0001) from 17.0 (Site A) and 17.1 (Site B), reaching 17.7 animals per litter in each. The mean number of weak piglets born per litter was not significantly affected by the updated vaccination schedule. Analysis of the number of mummified and stillborn piglets revealed a significant reduction of these parameters at both locations. The mean number of mummified piglets born per litter went down from 0.497 to 0.413 (

p=0.0255), and from 0.222 to 0.165 (

p=0.0019) in Site A and B, respectively. The mean number of stillbirths per litter in Site A and B decreased significantly from 1.65 to 1.42 (

p=0.0002), and from 1.46 to 1.29 (

p=0.0039). The mean farrowing rates (Site A: 89.7% and 90.8%; Site B: 88.6% and 88.0%) were not significantly altered by the vaccination.

DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Negatively affected by a great variety of infectious and non-infectious causes, reproductive performance in sows constitutes a top area of potential improvement in modern swine production. Reduced litter size, stillbirths, mummified fetuses, low viable piglets, abortions, and non-productive days collectively account for significant financial loss, irrespective of the herd size, its geographical location, or pig genetics. Among much less obvious agents affecting reproductive health in sows in an indirect manner, the IAV infection has been identified as one (

17).

Since the detection of IAV-positive cells outside the respiratory tract in pig has not yet been confirmed, it is reasonably assumed that the termination of pregnancy in affected sows is induced by hypercytokinemia (

14). Our study revealed significantly (

p=0.0025) reduced mean abortion rate (i.e. from 0.161% to 0.097%) in dams vaccinated against influenza A (H1N1)pdm09; however, since the alteration was observed only at one of the analyzed sites, such phenomenon could have been largely attributed to undetermined management and/or environmental factors. Available research related to the topic reported significant improvement of the abortion rate by a mean of 1.8 percent point in 57% of 137 German farms following the immunization (

15). Nevertheless, considering the mean size (n=448) and size range of the sow herd evaluated therein (38 to 5,600 heads), direct comparison is severely hampered, since these populations widely vary in their capability of developing enzootic IAV infections (

18,

19). Consequently, it can be hypothesized that these sow herds had experienced a great variety of spatiotemporal IAV spread patterns with individuals exposed to highly variable loads of cytokines at different production stages.

Similar reasoning can be applied to the return to estrus rate. A statistically significant (

p=0.0091) alteration of this index (from 2.23% to 2.97%) was noted only at one site of the farm taking part in the field trial. Accordingly, it could have been ascribed to other on-farm specific variables. As presented by Gumbert et al. (

15), the mean parameters observed by the authors before (13.52%) and after (10.18%) the vaccination were markedly different from those obtained in our research. Therefore, such values can automatically imply persistent involvement of other unidentified factors deteriorating the rate in previously analyzed German sow herds. As a natural consequence of relatively low rates of return to estrus and unaltered frequency of abortions, a significant deviation in farrowing following the immunization was not observed in our study.

Regardless of the fact that production targets set for the biologic performance of sows reared at the study farm were markedly different from benchmark range reported by Gumbert et al. (i.e. 13.2 vs 17.0 and 17.1 piglets born alive per litter from non-vaccinated sows) (

15), the results yielded during both investigations closely coincide with the improvement in the value being discussed. Analysis of the records revealed significant improvement by 0.7 and 0.6 piglets born alive per litter in Site A and B of the study farm respectively, whereas the investigation cited previously reported an increase by 0.6 piglets observed in 70.4% of the evaluated herds. Nevertheless, since both works present conclusions obtained from longitudinal field studies, the observation might have been heavily biased by several factors, including pig genetics, diverse management, feeding strategies, or co-infections. Our results show co-circulation of H1N1pdm09 and H1avN2; however, since all the sows reared at the location had been routinely immunized using a vaccine targeting H1N1, H3N2, H1N2, and data on potential cross-protection were not available, analysis of the influence of the latter subtype on reproduction was beyond the scope of our study.

According to the scientific literature, typical stillbirth rate in swine accounts for 5% to 10% of total born piglets (

20). Based on the available case studies, the IAV infection in sows was listed among contagious factors influencing this parameter (

13). Contrary to the findings reported by Gumbert et al. (

15), our research demonstrated a significant mean reduction of stillbirths per litter from 1.65 to 1.42 (

p=0.0002), and from 1.46 to 1.29 (

p=0.0039) which translates into a decrease from 8.85% to 7.43%, and from 7.87% to 6.79% of total pigs born per litter, respectively. The mean number of weak piglets born per litter remained unaltered.

Coincidently, a mean number of mummified fetuses reduced from 0.497 to 0.413 (

p=0.0255), and from 0.222 to 0.165 (

p=0.0019). Since similar outcomes of the vaccination has not yet been reported in the literature, the alterations deserve further investigation.

CONCLUSION

A significant improvement in selected key reproductive performance indicators following the vaccination against the influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus was achieved, i.e. decreased abortion rate, increased mean number of piglets born alive, decrease in the number of mummified and stillborn piglets. Our findings highlight the role of less obvious problems affecting porcine reproduction. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to enhance the understanding of the role of the virus in sow reproductive performance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial conflict of interest regarding authorship and publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was supported by the Institute of Veterinary Medicine of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

PC performed research concept and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, writing the article, critical revision of the article, final approval of the article. AW performed research concept and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, writing the article, critical revision of the article, final approval of the article. TM conducted data analysis and interpretation, writing the article, critical revision of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

10.2478/macvetrev-2026-0010

10.2478/macvetrev-2026-0010