Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative joint disease in dogs, characterized by progressive cartilage deterioration, chronic pain, and reduced mobility. This prospective, cross-sectional study aimed to determine the prevalence of OA-associated pain and identify key risk factors in a cohort of 259 dogs through an owner-completed online survey. The survey incorporated three validated pain and mobility assessment tools: the Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs (LOAD), the Helsinki Chronic Pain Index (HCPI), and the Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI). Dogs exhibiting consistent signs of pain across all three tools (n=56) were selected for a full clinical evaluation, and diagnostic imaging. Most dogs were purebred (80.7%), male (61.8%), overweight (61.0%), and 3-9 years old (57.5%). Pain scores from all three assessment tools revealed significant associations between severity of OA and age, weight category, and body condition score (BCS). Notably, BCS was the strongest predictor of moderate to severe OA, followed by weight category and age. Notably, a discrepancy was observed between owner-reported mobility concerns (28.6%) and the clinical findings, highlighting the limitations of subjective assessment. These findings confirm that advanced age and, more significantly, excess body weight are primary contributors to the severity of canine OA. Furthermore, the study underscores the importance of objective diagnostic tools and owner education in the early identification and management of OA. Preventive strategies, including weight control, regular monitoring, and timely interventions, are crucial for improving outcomes in affected dogs.

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a significant concern in veterinary medicine, representing one of the most prevalent degenerative joint diseases in dogs. Characterized by the progressive degeneration of articular cartilage, this condition is accompanied by inflammation processes resulting in chronic pain, reduced mobility, and compromised quality of life (

1,

2,

3). This condition affects approximately 20% of dogs over one year of age, with prevalence rising to 60% or more in those aged five years and older, underscoring aging as a major risk factor in OA development (

4).

The etiology of OA in dogs is complex and multifactorial. Key risk factors include age, weight, body condition score (BCS), genetics, and prior joint trauma (

5). Obesity significantly contributes to both the onset and progression of OA, as excess weight impairs cartilage damage and inflammatory processes (

6). The terminology surrounding joint degeneration has evolved, with “osteoarthritis” now widely adopted over “osteoarthrosis” in clinical and research settings, acknowledging the integrated degenerative and inflammatory aspects of the disease (

1,

7). OA typically develops gradually, causing chronic pain that may remain undetected until significant mobility issues or behavioral changes emerge (

8). This delayed recognition is often compounded by the owner's misperception of pain in dogs, leading to postponed intervention, disease progression, and reduced quality of life (

3,

9). Therefore, early detection and comprehensive understanding of canine OA are essential for timely and effective disease management (

3,

10).

While key risk factors such as age and obesity are well-documented, their prevalence and impact within different canine populations remain inadequately explored. Much of the large- scale epidemiological research on canine OA originates from specific geographic regions like the UK and the US, where the canine populations are predominantly neutered (

11). However, neuter status itself has been identified as a significant risk factor for OA. This creates a distinct research gap: there is a lack of data on OA prevalence and owner- perceived pain in canine populations with different demographic characteristics, such as those with a higher proportion of intact animals.

This study aimed to address these gaps by providing a comprehensive assessment of OA in a previously under-documented canine population in North Macedonia, incorporating three validated pain assessment tools: Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs (LOAD), Helsinki Chronic Pain Index (HCPI), and Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI). Each questionnaire included a pain scale to evaluate the intensity of pain experienced by the dogs. Additionally, the study sought to identify key risk factors associated with OA development and provide insight into the diagnosis and management of OA cases in clinical practice.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This prospective, cross-sectional study was based on collected data through an online survey completedby 259 dogownersfrom North Macedonia. All participating dog owners provided informed consent by voluntarily completing an online survey that contained detailed information regarding the study's purpose, data collection methods, and intended scientific applications. A full version of the questionnaire used in this study is available at:

https://forms.gle/fjToDKs4QNmUDfSU9.

The questionnaire was organized into four sections: (

1) demographic data, including sex, age, breed, body weight, and neuter status; (

2) environmental and lifestyle factors, such as movement restrictions, access to slippery surfaces, and available walking space; (

3) owner-perceived mobility issues and pain-related clinical signs; and (

4) three validated pain and mobility assessment tools. Owners completed the questionnaires based on their routine observations of the dog’s behavior, and the resulting scores were used to identify dogs suspected of having OA for further clinical evaluation.

Pain and mobility were assessed using three validated owner-completed questionnaires: the Canine Brief Pain Inventory (CBPI), the Helsinki Chronic Pain Index (HCPI), and the Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs (LOAD). LOAD includes 13 items scored from 0 to 4, producing a total score between 0 and 52; HCPI includes 11 items scored from 0 to 4, for a range of 0 to 44; and CBPI consists of 10 items scored from 0 to 10. For analytical purposes, a mean index value was calculated for each dog by averaging their responses per questionnaire. This resulted in a final score range of 0–10 for CBPI, and 0–4 for both HCPI and LOAD. These index values were treated as continuous variables in the statistical analysis, with higher scores indicating more severe pain or mobility impairment. A subset of 56 dogs (22%) that exhibited pain across all three assessments were selected for further clinical evaluation. Dogs were excluded from the study if they had received non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) within the previous two weeks, glucocorticoids or opioids within the last four weeks, or if they had any clinically significant medical conditions that required daily medication. Owners of the selected dogs were contacted by phone to obtain additional information and consent for further evaluation.

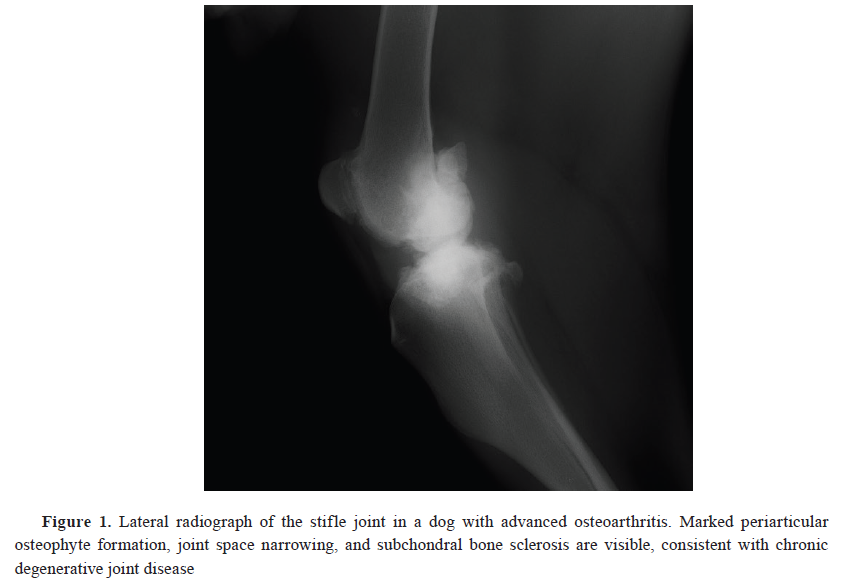

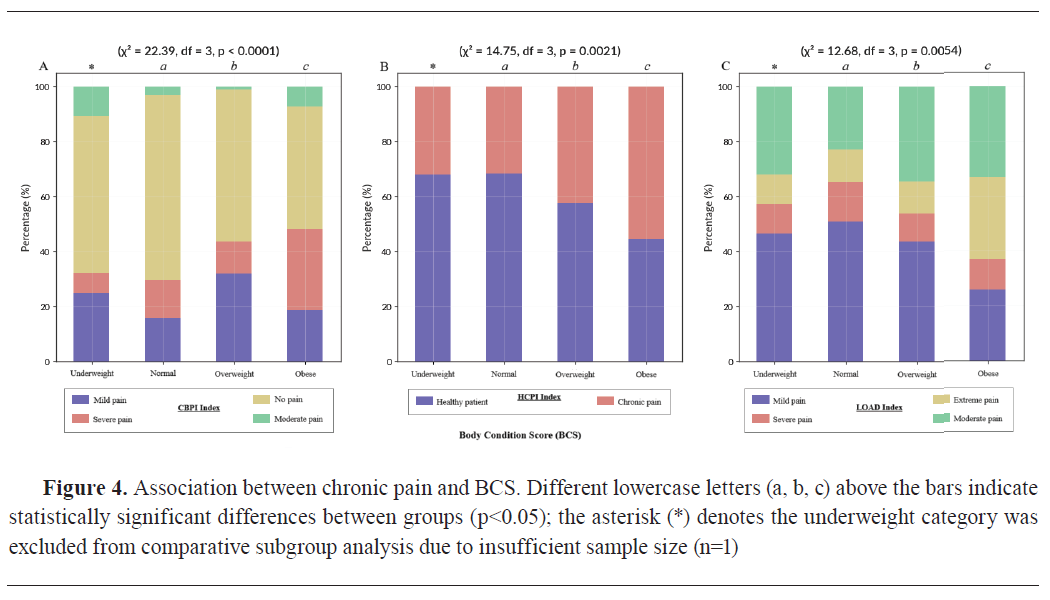

The clinical evaluation included a detailed history of the dog’s medical background, a physical examination, and neurological and orthopedic assessments to rule out other causes of pain. Gait analysis was performed using video recordings to support clinical observation of movement abnormalities. Body condition scores (BCS) were recorded using a 9-point scale. The BCS categories were: 1–3 (underweight), 4–5 (ideal), and 6–9 (overweight to obese) (

12). Radiographic imaging was used to confirm the presence and severity of OA in the affected joints (

Fig. 1). Following diagnosis, dogs confirmed to have OA and associated pain were recommended and offered a comprehensive, multimodal treatment plan in consultation with their owners, adhering to ethical standards of veterinary care.

The demographic data were classified into predefined categories. Dogs were divided into five age groups: young (≤3 years), junior (3–5 years), adult (5–9 years), mature (9–13 years), and geriatric (≥13 years). Breeds were categorized as mixed breed or purebred, and sex was classified as male or female. Based on body weight, dogs were grouped into small (1–10 kg), medium (11–26 kg), large (27–45 kg), and giant (≥46 kg) breeds. Neuter status was classified as intact, castrated (males), or spayed (females). Additionally, the questionnaire included owner-reported perceptions of pain, exposure to slippery surfaces, and restrictions in walking space.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.4.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics, pain index scores, and OA severity levels. Chi-Square tests were applied to assess associations between OA severity and categorical variables, such as age, weight category, and BCS. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of moderate/severe OA, with results presented as Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). Standard Error of the Mean (SEM) was calculated for pain index scores to assess variability, and p-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Grammarly platform (

https://grammarly.com) was used exclusively for language refinement, including grammar correction, synonym polishing, and improving the textual flow of the manuscript. The software was not used for generation of scientific content. The authors are ultimately responsible and accountable for the accuracy of all contents of the submitted paper, including the information provided by use of AI-assisted technologies.

RESULTSDemographic data

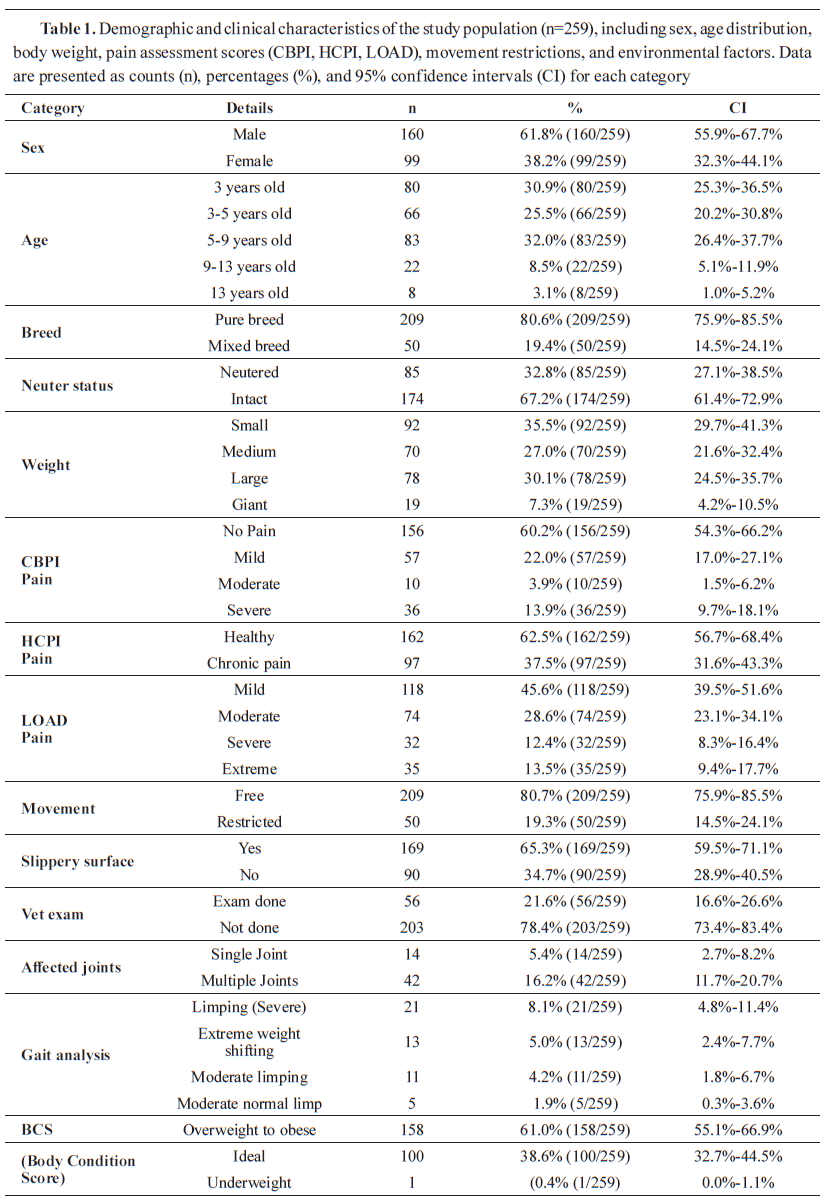

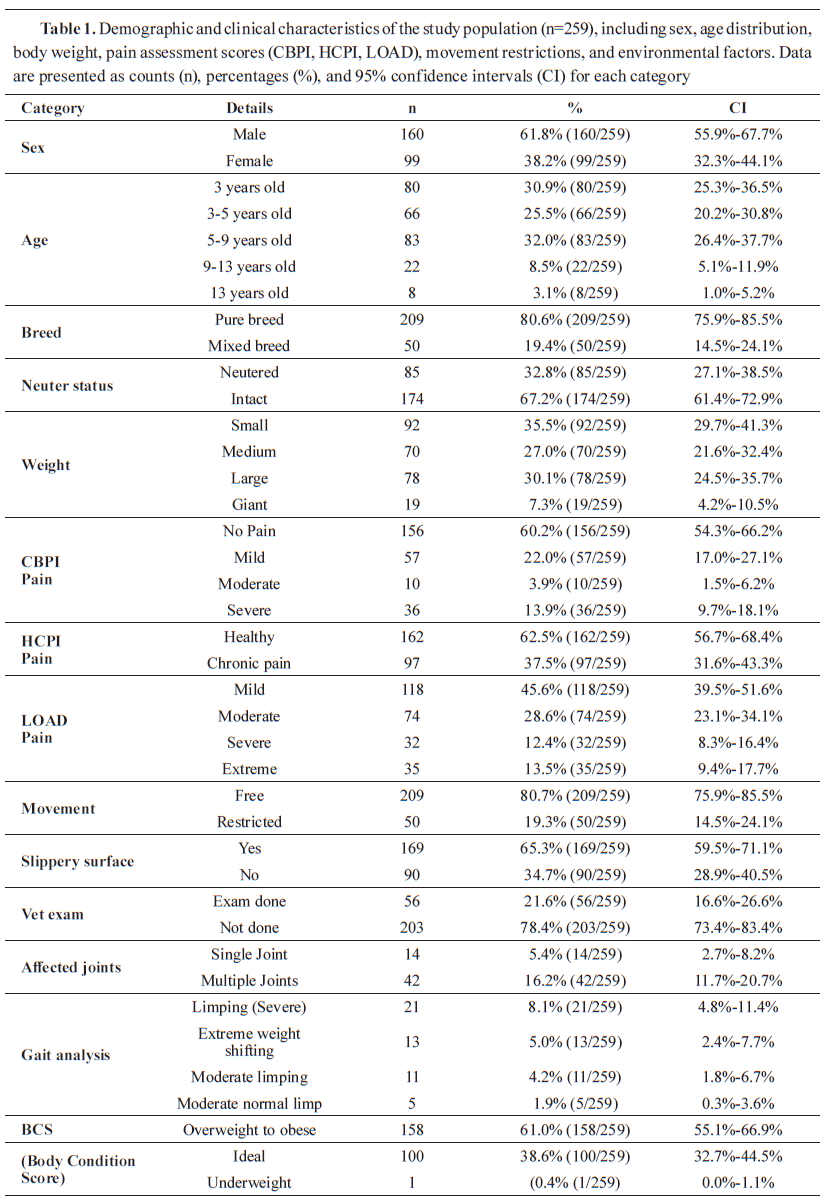

The study included 259 dogs, with demographic data summarized in

Table 1, compiled from completed owner questionnaires.

The majority of dogs involved in this study were male (61.8%). Most dogs were between 3 and 9 years old, with the largest proportion (32.0%) falling within the 5–9 years category. Regarding weight, dogs were evenly distributed across the three categories: small (35.5%), medium (27.0%), and large (30.1%), with a smaller proportion (7.3%) classified as giant breeds. Most dogs were purebred (80.7%) and intact (67.2%), while 19.3% were mixed breed and 32.8% were neutered. Body condition assessment revealed that overweight dogs were the most prevalent (61.0%), while a smaller proportion of the dogs had ideal weight (38.6%) or were underweight (0.4%).

The mobility evaluation revealed that while most dogs (80.7%) had free movement, a smaller proportion (19.3%) experienced some form of restriction. Gait abnormalities were detected in 21.2% of dogs, most commonly presenting as limping, extreme weight shifting, or moderate asymmetry in movement. Joint involvement analysis indicated that 16.2% of dogs had multiple joints affected, while 5.4% had a single joint affected.

The pain assessments using the CBPI questionnaire showed that 39.8% of the dogs had mild to severe pain. Similarly, 37.5% of the dogs were classified as having chronic pain in the HCPI questionnaire. LOAD questionnaire indicated that 45.6% had mild pain, whereas 39.7% had moderate to extreme pain.

The dogs with high pain scores on the questionnaires were called for further evaluation. Fifty-six dogs (22%) underwent clinical examination, confirming OA in all cases. Gait analysis showed that while 22% of dogs exhibited visible lameness, many owners did not recognize these movement abnormalities. Additionally, owner-reported mobility issues (28.6%) did not always correlate with observed clinical signs.

Pain assessment using CBPI, HCPI, and LOAD questionnaires

Pain assessment using CBPI, HCPI, and LOAD questionnaires

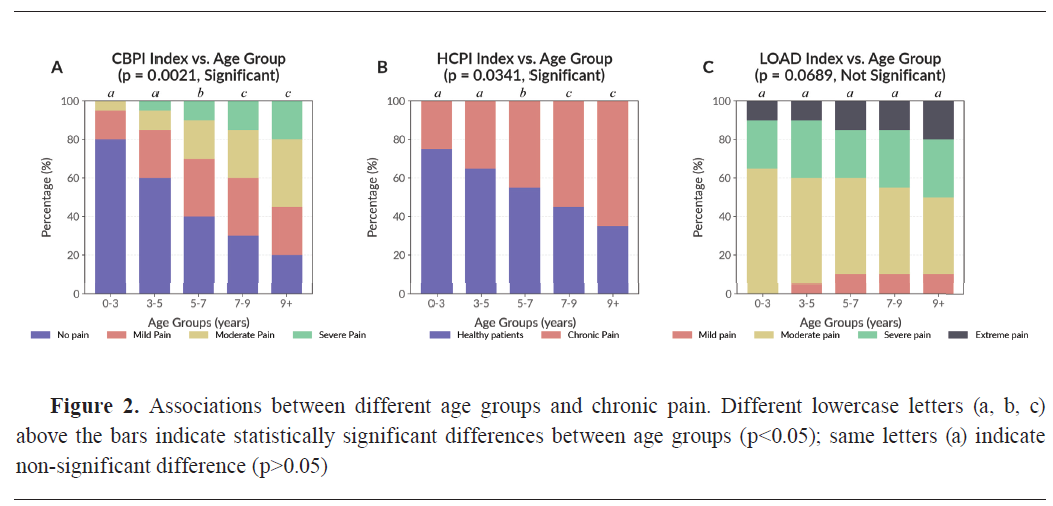

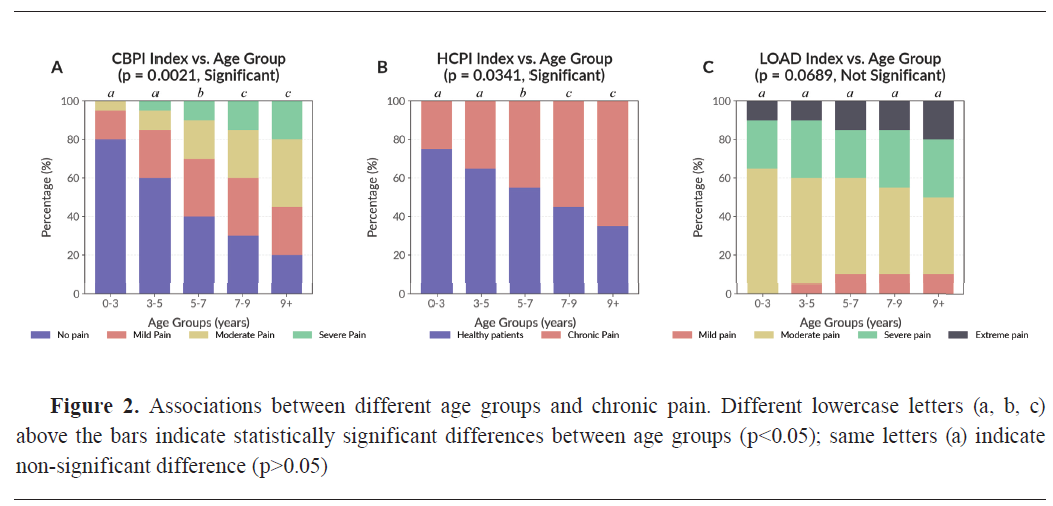

The Chi-Square analysis revealed a significant association between chronic pain and age by using CBPI (χ²=14.62, df=4, p=0.0021) and HCPI (χ²=10.35, df=4, p=0.0341) (

Fig. 2A and

2B). Among dogs aged 9 years and older (n=30, 11.6%), 22 dogs (73.3%) were classified as experiencing moderate to severe pain based on CBPI, while only 8 dogs (26.7%) were classified as having no or mild pain. In contrast, dogs aged 0–3 years (n=80, 30.9%) were predominantly classified as healthy or experiencing mild clinical signs, with only 12 dogs (15.0%) showing moderate or severe pain.

Further analysis of CBPI scores confirmed that older dogs had significantly higher chronic pain, with mean CBPI values increasing with age (Mean±SEM: 9+ years = 2.45±0.15; 5–9 years, n=83, 32.00%=1.87±0.13). Similarly, HCPI scores were highest in the oldest age group (9+ years=1.68±0.11; 5–9 years=1.42±0.09), with a comparable age-related pattern. LOAD was not significantly associated with age (χ²=8.74, df=4, p=0.0689) (

Fig. 2C).

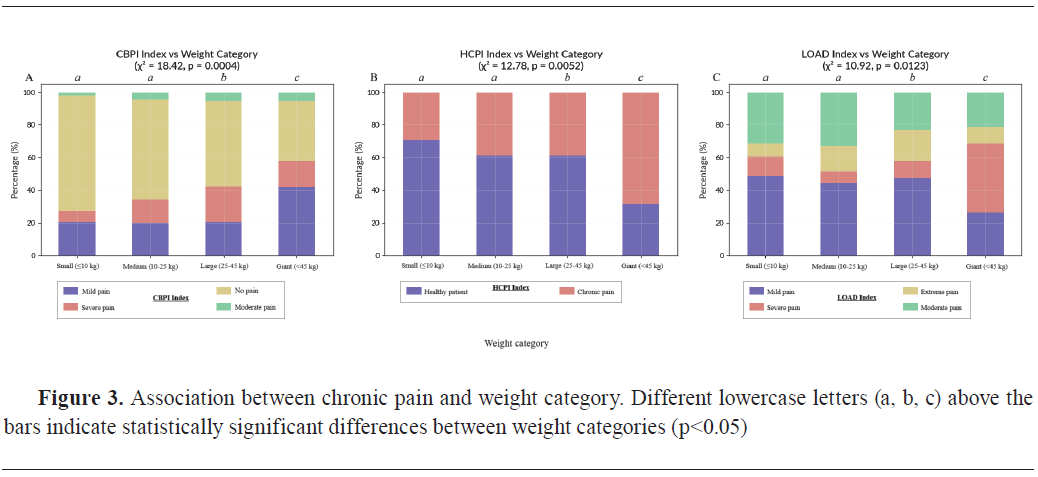

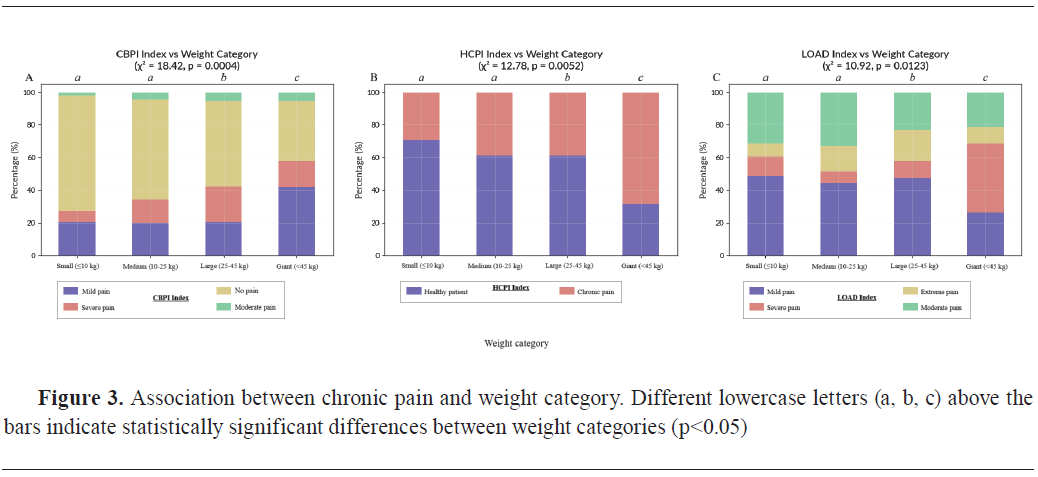

A significant relationship was observed between chronic pain scores and weight category across all three pain questionnaires (CBPI, HCPI, and LOAD). CBPI showed a strong association with weight (χ²=18.42, df=3, p=0.0004) (

Fig. 3A). Among giant breed dogs (n=19, 7.3%), 15 dogs (78.9%) exhibited moderate to severe pain, with a mean CBPI score of 2.52±0.18. In the large breed group (n=78, 30.1%), 49 dogs (62.8%) were similarly affected, with a mean CBPI score of 2.30±0.14. In contrast, medium breeds (n=70, 27.0%) and small breeds (n=92, 35.5%) showed lower proportions of high pain scores - 38.6% (n=27) and 22.8% (n=21), respectively.

Similarly, HCPI was significantly correlated with weight category (χ²=12.78, df=3, p=0.0052) (

Fig. 3B). The highest mean HCPI scores were observed in giant (1.88±0.12) and large breeds (1.56±0.10), consistent with increased chronic signs of pain in heavier dogs. Additionally, LOAD was significantly associated with weight (χ²=10.92, df=3, p=0.0123) (

Fig. 3C), with mean LOAD scores rising with body size (Giant breeds: 3.04±0.20; Large breeds: 2.87±0.15), confirming that mobility impairments were more common in heavier dogs.

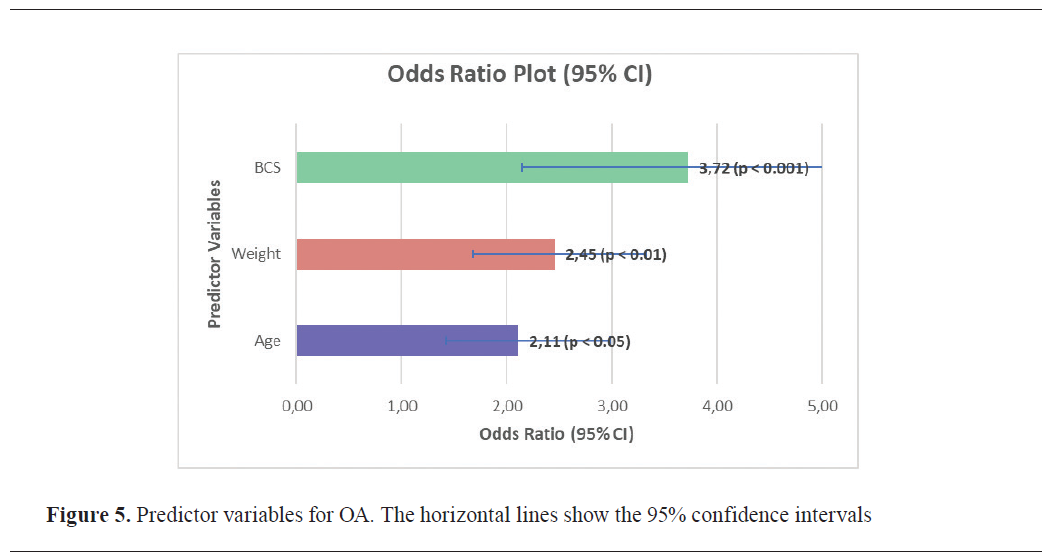

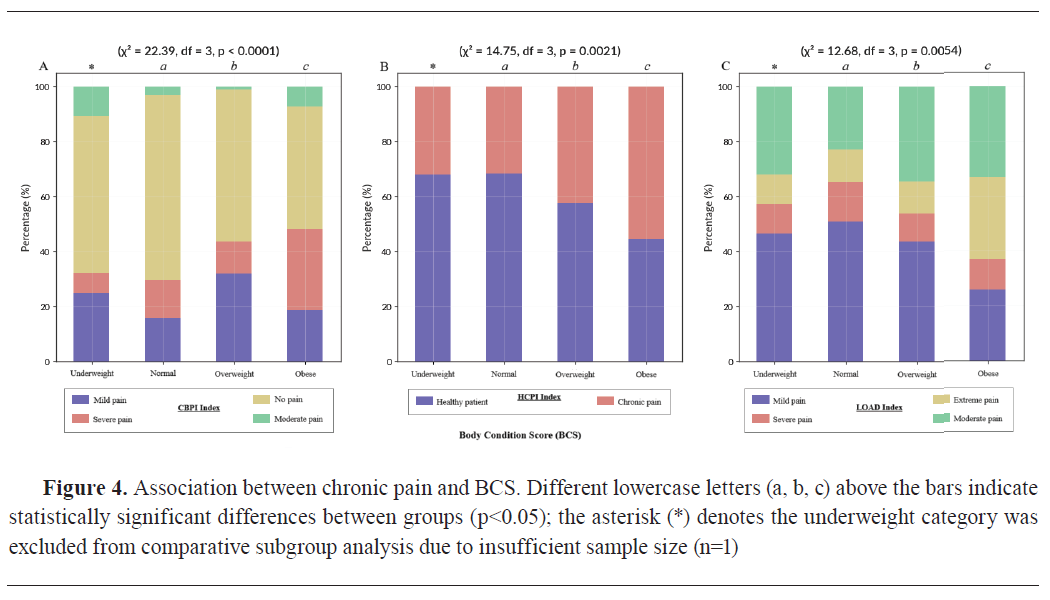

Body Condition Score (BCS) was strongly associated with chronic pain scores. CBPI showed a highly significant relationship with BCS (χ²=22.39, df=3, p<0.0001) (

Fig. 4A). Among obese dogs (n=89, 34.4%), 65 dogs (73.0%) were classified as having moderate to severe pain, with a mean CBPI score of 2.67±0.16. In the overweight group (n=69, 26.6%), 41 dogs (59.4%) showed moderate to severe pain (2.45±0.14), while in the normal BCS group (n=100, 38.6%), only 24 dogs (24.0%) were affected (1.89±0.12). One dog (0.4%) was classified as underweight and was excluded from subgroup analysis due to insufficient sample size.

Similarly, HCPI was significantly associated with BCS (χ²=14.75, df=3, p=0.0021) (

Fig. 4B), with mean scores highest in obese dogs (1.92±0.13), followed by overweight dogs (1.65±0.11), and lowest in dogs with normal weight (1.33±0.09).

LOAD also showed a significant association with BCS (χ²=12.68, df=3, p=0.0054) (

Fig. 4C), with chronic pain scores highest in the obese category (3.21±0.17), further confirming the impact of increased body fat on functional mobility and pain perception.

Predictor analysis

Predictor analysis

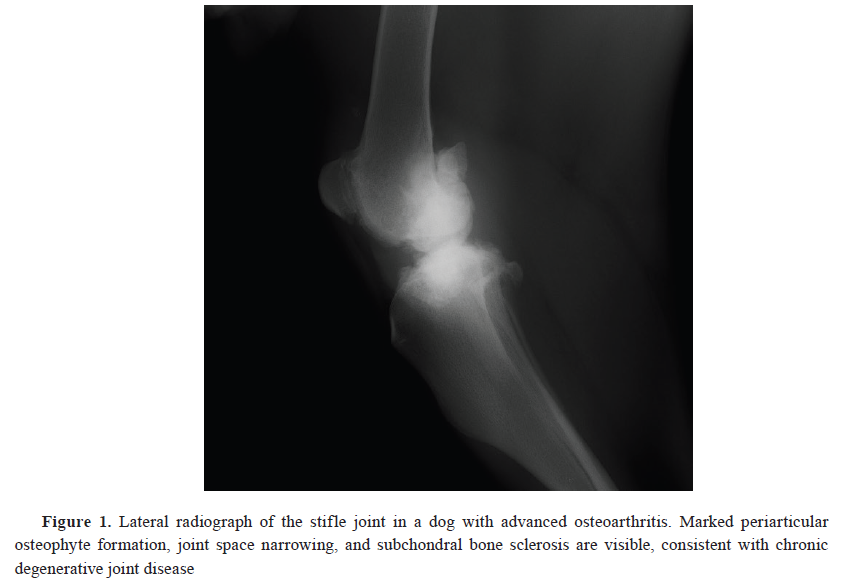

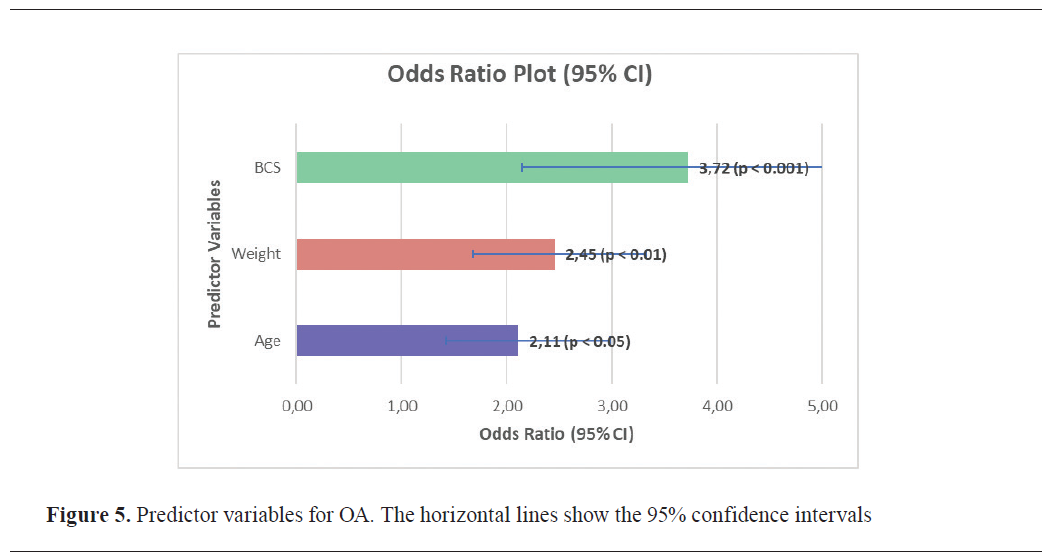

Among the total study population (n=259), 102 dogs (39.4%) met the criteria for moderate to severe OA (CBPI≥2). BCS was the strongest predictor of OA severity (p<0.001). Obese dogs (n=89, 34.4%) were 3.72 times more likely (95% CI: 2.14–5.91) to experience moderate to severe OA compared to dogs with normal body condition (n=100, 38.6%). In this group, 65 of 89 obese dogs (73.0%) had CBPI≥2, compared to 24 of 100 dogs (24.0%) with normal BCS. Weight category was also significantly associated with OA severity (p<0.01). Dogs classified as large or giant (n=97, 37.5%) had 2.45 times higher odds (95% CI: 1.68–3.32) of developing moderate to severe OA compared to smaller dogs. Among large and giant dogs, 64 (66.0%) had CBPI≥2, compared to 38 of 162 (23.5%) in the small and medium group. Age was also a significant predictor (p<0.05), with dogs aged 9 years and older (n=30, 11.6%) showing 2.11 times higher odds (95% CI: 1.42–2.98) of developing moderate to severe OA compared to younger dogs. In this group, 22 dogs (73.3%) exhibited CBPI≥2. The 95% confidence intervals for BCS and weight category did not cross 1.0, confirming their strong predictive value (

Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Body weight and BCS as predictors of OA severity

The findings from this study identify excess body weight and, more specifically, a high body condition score (BCS) as powerful predictors of OA severity and associated chronic pain. Our analysis revealed that BCS was the single strongest predictor of moderate to severe OA. Body weight and obesity have been strongly associated with chronic pain severity in dogs, impacting the progression and clinical signs of OA. Research indicates that larger breeds, particularly large and giant-sized dogs, exhibit significantly higher pain scores when assessed using various pain assessment tools such as the CBPI and LOAD questionnaire (

11,

13) . This observation supports earlier findings suggesting that the increased mechanical load on the joints in the larger breeds accelerates cartilage degeneration, thus intensifying OA-related clinical signs and chronic pain (

1,

10). Cumulative mechanical stress associated with higher body weight directly affects joint degeneration and alters biochemical processes within the joint structures (

1). Moreover, body condition score (BCS) emerges as a powerful predictor of OA severity, with studies revealing that obese dogs are more likely to develop moderate to severe OA compared to their normal-weighted equivalents (

14). This finding underscores the critical importance of managing body weight as a preventative measure against the development of OA, highlighting significant implications for veterinary practice. Effective weight management strategies, including dietary modifications and controlled exercise programs, are essential components of OA treatment protocols aimed at easing clinical signs and improving the quality of life in affected dogs (

5). These results reinforce that increased body weight, obesity and older age significantly increase the likelihood of developing severe OA, supporting early detection and weight management as key preventive strategies.

Current veterinary recommendations highlight the need for maintaining a healthy weight to prevent increased mechanical stress on joints, further supporting the need for a proactive approach to managing canine obesity (

5,

6). Overweight dogs have been documented to have higher leptin levels compared to their leaner counterparts, which correlates with risk factors for developing OA (

4). This increased leptin concentration not only reflects excess adipose tissue but also serves as a mediator of inflammation, which contributes to the pathogenesis of OA. The inflammatory state associated with obesity leads to the activation of inflammatory pathways that can intensify joint degeneration (

15). Furthermore, leptin association with inflammation underscores the complexity of OA, where mechanical stress due to excessive body weight is compounded by biochemical factors such as inflammatory cytokines released in response to fatty tissue, particularly in overweight dogs (

4,

15).

Age as a risk factor for OA

In this study, age has been identified as the significant risk factor for chronic pain and the progression of osteoarthritis (OA) in dogs, as indicated in CBPI and HCPI scores. Dogs aged nine years and older demonstrated increasing pain levels, consistent with literature suggesting age-related joint degeneration and cumulative mechanical stress as contributors to OA development (

11). This age related increase in pain may be attributed to the exacerbation of biomechanical stress placed on aging joints, leading to degradation of articular cartilage over time, which is a characteristic of OA (

1,

4).

The phenomenon underscores the need for observant monitoring of older dogs, as they are more susceptible to complications of OA, which include chronic pain and decreased mobility (

5,

6). Interestingly, while the CBPI and HCPI scores indicate increased pain with age, the LOAD instrument did not show a significant association with age (p=0.0689). This suggests that LOAD may not be as sensitive in detecting differences in pain severity across different age groups. Additionally, pain perception and functional impairment may not progress linearly or be perceived equally by owners. One possible explanation is that owners may perceive mobility issues in their dogs as an inevitable consequence of aging, and therefore under-report these items on the LOAD questionnaire. In contrast, the CBPI and HCPI include signs of pain that owners may not immediately associate with aging. This highlights a critical note in OA assessment: the tools used can capture different dimensions of the disease, and owner perception remains a powerful mediating variable. Therefore, the multifactorial nature of OA, compounded by the variability in individual pain perception among dogs, further complicates the assessment of OA-related pain and emphasizes the need for diverse pain assessment tools (

16,

17).

Owner recognition and reporting discrepancies

An important discrepancy exists between owner-reported pain signs in dogs and objective clinical findings regarding OA. Our study revealed that while 28.6% of dog owners reported mobility issues, clinical gait analyses confirmed lameness in only 22% of cases, with subtle movement abnormalities often remaining unnoticed by dog owners. This suggests that many owners may not be familiar with the early signs of OA, such as reluctance to jump, stiffness following rest, or changes in behavior, potentially leading to delayed intervention and treatment (

17,

18).

Research consistently highlights that pet owners commonly attribute mobility problems to aging rather than specific conditions like OA, which often result in significant underdiagnosis and insufficient pain management in affected dogs (

4,

18). The lack of recognition of subtle signs of OA poses a significant barrier to timely treatment initiation. Studies have indicated that doctors of veterinary medicine and pet owners may have different perceptions of the severity of clinical signs of OA (

16,

19).

Educating pet owners about the clinical signs of OA is crucial for promoting early detection. Improved owner awareness can facilitate timely veterinary visits and interventions, which are pivotal in managing the progression of the disease (

17,

18). Effective communication strategies that provide dog owners with clear information about what to observe, like changes in activity levels or reluctance to engage in favorite activities, can significantly enhance the management of OA (

5).

Implications for OA management

Given the strong association between age, body weight, and the severity of OA in dogs, a complex management approach is essential to effectively mitigate the effects of this condition. This approach must encompass several components:

Weight management: Implementing a calorie- controlled diet and regular exercise programs is crucial for overweight dogs. Weight management not only relieves stress on joints but also plays a significant role in reducing pain and enhancing mobility. Research indicates that obesity significantly increases the risk of developing OA, making it essential to maintain an optimal BCS (

11,

14). Specifically, a higher BCS correlates with an increased prevalence of OA (

13). Customized nutritional and exercise plans specifically designed for dogs can lead to significant improvements in their overall health and may directly contribute to a slower progression of OA (

5).

Owner education: Educating dog owners about the early signs of the disease is fundamental for improving outcomes. Many owners may incorrectly indicate mobility issues to natural aging rather than recognizing them as potential indicators of OA (

20). Regular veterinary check- ups and the use of validated pain assessment tools can empower owners to identify subtle changes in their dog’s behavior and mobility (

18,

21). Taking this proactive approach enables the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine to intervene early, making it easier to manage the disease more effectively.

Clinical assessment: Incorporating objective assessments, including gait analysis and advanced imaging techniques such as radiographs, is essential in routine evaluations of dogs suspected of having OA. These assessments can reveal lameness or subtle movement abnormalities that may not be noticeable during a typical veterinary examination (

22,

23). Studies show benefits of objective mobility assessments in accurately diagnosing and monitoring the progression of OA, ultimately guiding treatment decisions (

16,

18).

"Null" findings

This study found no statistically significant associations among sex, breed, neuter status and osteoarthritis (OA) in dogs. While this appears to contradict some existing literature, these null findings are valuable given the inconsistent results across canine OA research. Reporting such "null" results is essential to combat publication bias, which favors statistically significant findings and thereby distorts the overall evidence base (

4).

Several factors explain these results. First, this study used owner-reported pain and quality of life measures rather than veterinary diagnostic codes or radiographs, which correlate poorly with actual clinical signs and the pain experienced by the animal (

24). Second, while the 259-dog sample was adequate to detect strong effects of age and body condition, it likely lacked power to identify the small effect sizes typically associated with sex or breed that require much larger samples. For example, the large VetCompass study (N=455,557) found a small but statistically significant increased risk in males (OR=1.19), while another large Banfield study (N=131,140) described the effect of sex as "minimal" and "not consistently significant in all breeds tested" (

11). Third, this population was unique with 67.2% intact dogs, unlike most UK/US populations where neutering is prevalent and represents a strong OA risk factor (

11).

The results suggest that in populations similar to this study, sex, breed, and neuter status may not be primary drivers of owner-perceived chronic pain. These null findings are essential for providing balanced evidence, while highlighting how methodology and population characteristics influence OA risk factor analysis.

Study limitations

This study has several important limitations that must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design allows identification of significant associations (such as between BCS and OA) but cannot establish causation. The convenience sampling method, using data from an online survey voluntarily completed by dog owners, may introduce selection bias since owners who are more engaged with their pet's health may be more likely to participate, potentially limiting the representativeness of the study population among all dog owners in North Macedonia. Additionally, the primary data relies on owner-completed questionnaires, which introduce subjectivity concerns, as the study's own findings suggest there can be significant discrepancies between owner perception and clinical reality. Finally, clinical examinations were only performed on a sub-group of 56 dogs selected based on high pain scores across all three assessment tools, which was necessary for the study design but means that correlations between owner reports and clinical findings were not assessed in dogs with mild or no signs of pain.

Future research directions

Future studies should focus on longitudinal monitoring of OA progression in dogs undergoing weight management interventions. Investigating the efficacy of multimodal therapies, which may include NSAIDs, physical therapy, and nutraceuticals, is vital (

3,

6). The studies should evaluate how these treatments can help manage pain and prevent mobility loss, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for dogs suffering from this condition.

Additionally, developing more sensitive, owner- focused educational tools that improve recognition of subtle signs of OA could help bridge the gap between clinical findings and owner perceptions. Exploring the potential benefits of telemedicine and home monitoring technology may also provide valuable insight into real-time assessment of OA progression in the home environment.

CONCLUSION

This study confirms that age, weight, and obesity are significant contributing factors to the development of OA in dogs, reinforcing the importance of early detection, weight management, and comprehensive clinical assessments for effective OA management. Our findings highlight that Body Condition Score serves as a powerful predictor of pain severity, suggesting that weight management should be a key component of OA prevention and treatment strategies. The observed gap between owner-reported signs and clinical findings highlights the need for enhanced owner education about the subtle signs of OA and the importance of regular veterinary assessment. This discrepancy underscores the value of using validated pain assessment tools to objectively evaluate pain levels and mobility limitations in dogs with OA.

For veterinary practitioners, our results suggest that implementing a multimodal approach, where we combine weight management, owner education, and regular clinical assessments, can significantly improve outcomes for dogs with OA. Early intervention, particularly in at-risk populations such as older dogs and overweight individuals, can help mitigate the progression of this condition and improve the quality of life for the affected animals.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial conflict of interest regarding authorship and publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was supported by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Skopje and the University Veterinary Hospital at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Skopje.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

JV conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. KI supervised the clinical examination and the questionnaires and contributed to interpretating the results. BC was included in analyzing the questionnaires and interpreting the results. PT, BD, DB and FT were included in the clinical examinations of the patients and interpreted the results. MN and IS participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript. AC was involved in manuscript writing and reviewing. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

doi.org/10.2478/macvetrev-2026-0011

doi.org/10.2478/macvetrev-2026-0011